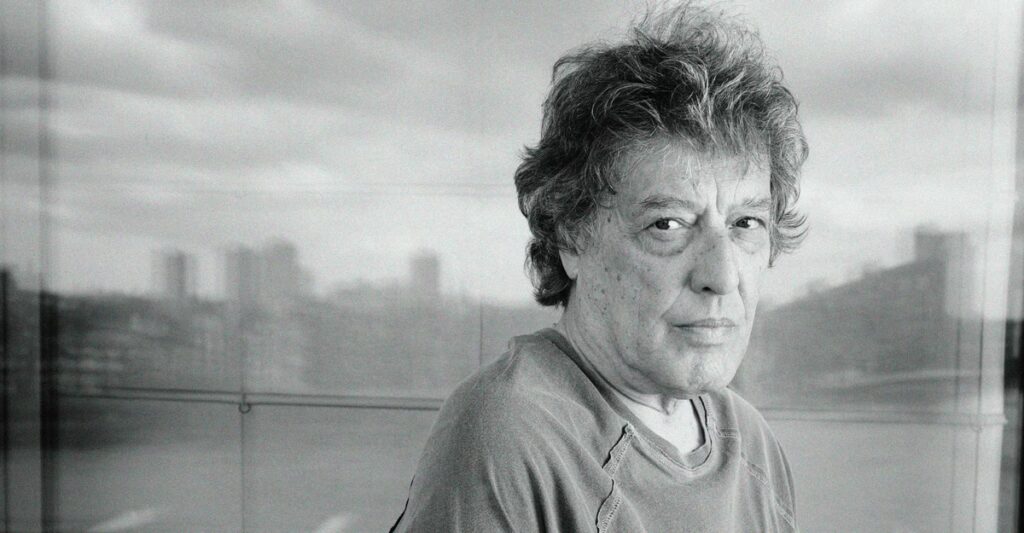

At necessary moments in my life, Tom Stoppard, the preeminent British playwright who died last Saturday, has popped up like one of his frenetic characters, spouting enigmatic lines and leaving me thrilled, confused, and somehow heartened. The first time, I was in graduate school, reading Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, his breakthrough homage to Hamlet; I was surely thinking grad-school thoughts when I came across the line “the toenails, on the other hand, never grow at all”—the best bad joke ever. More recently, it happened in London, the night before the first COVID lockdown in 2020, soon after Leopoldstadt, his play about a Jewish family in 20th-century Vienna, had opened. Was I just a little disappointed in the play? Maybe—but in retrospect I cherished this last night of freedom, of community, of collaborative artistic expression. Leopoldstadt is possibly his most personal play (Stoppard discovered the extent of his Jewish identity only in his 50s); it stayed with me throughout the pandemic, and after.

Of all my Stoppard moments, The Coast of Utopia looms most magnificent. This wildly ambitious epic of the mind opened at the National Theatre, in London, in the summer of 2002; it is made up of three plays with a total running time of nine hours, and it features a group of 19th-century Russian writers and activists, some famous and some obscure, who argue about political philosophy and muddle through messy lives. I wish I’d had the courage to sit through one of the marathon performances of all three plays at once—instead I saw the first installment, Voyage, and followed it a couple of weeks later with Shipwreck and Salvage on consecutive evenings. Even now, after more than two decades, I can still feel the mounting excitement as I began to see what Stoppard was up to, which was writing about resistance to totalitarianism in a way that was unmistakably human, grounded in family and the grit of personal experience.

And in humor: Stoppard can’t help being funny. Born in Czechoslovakia in 1937 and already an expatriate by the age of 2, he told journalists, after Rosencrantz and Guildenstern had made him famous overnight, that he was a “bounced Czech.” Wordplay is the foundation of his humor, but he’s a dramatist at heart; his text demands performance, often brightened by the kind of clowning that Shakespeare loved and Beckett made essential to modern theater. Peals of laughter sounded all the way through The Coast of Utopia, from both the audience and the stage, beginning with the banter of the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, his four sisters, and his parents on their estate in the 1830s; and trailing across Europe as exiled Russians and other assorted revolutionaries seek refuge and relevance. One of the funnier scenes in The Coast of Utopia (as I remember it) depicted the unmistakably Russian Alexander Herzen trying out Britishness in London by brandishing a brolly and drawling, “I say, I say.”

Most people won’t have heard of Herzen, a giant in the distant landscape of 19th-century Russian political thought, who according to Stoppard was Russia’s first self-proclaimed socialist. Bakunin is better known, as is the novelist Ivan Turgenev; other characters based on real people—Vissarion Belinsky, a literary critic; Nikolai Stankevich, a poet and philosopher who died at age 26—are now largely forgotten, as is Herzen’s great friend Nikolai Ogarev. (One of the minor characters is Karl Marx, whom Herzen despised.) These men debate at great length, and if Stoppard hadn’t made them seem real and important onstage, the audience might have wilted. Providing relief and contrast are the sisters, daughters, mothers, wives, mistresses, and nursemaids, all of whom also have views on ideal social order.

[Read: A nine-hour resurrection]

Does it sound like the stage was crowded? Hectic is a favorite Stoppard mode. The production called for more than 150 costumes to be worn by a company of at least 30 actors (not to mention the unspeaking serfs). Part of the pleasure was admiring the skill with which the playwright juggled his characters and cut back and forth in time to tell the tale. I’m sure I was lost at times, and some of the jokes probably sailed far over my head. But the full-tilt dialogue—a Stoppard trademark—and the thrust of the action against a momentous historical background always made sense to me. We move from the dismay of czarist oppression in the 1830s to the dangerous excitement of the 1848 revolution in France to the brief dashed hope represented by the emancipation of the serfs in 1861—a halting, frustrated battle against tyranny and injustice.

The dramatic arc of the work teaches us to resist any totalizing doctrine promising a utopian future. Herzen reminds us that “there is no landfall on the paradisal shore,” and that “our meaning is in how we live in an imperfect world, in our time.” The domestic scene—affairs and betrayals, sudden deaths and new romances, all the hubbub of the private lives of these great and would-be great men—always undercuts the grand designs of political philosophy.

In the end, I fell in love with Herzen, the illegitimate son of a Russian nobleman who spent six years in prison and internal exile without compromising his ideals. He left Russia in 1847 (a year after his father had died, leaving him a large fortune), and never returned. But he also never stopped being Russian to the core, even with an umbrella in his hand. I looked up the speech he makes in the last scene of the play—in a dream, addressing Marx and Turgenev: “It takes wit and courage to make our way while our way is making us,” Herzen tells them, “with no consolation to count on but art and the summer lightning of personal happiness.”

I wonder whether it was Alexander Herzen I fell in love with. Maybe it was actually Tom Stoppard.

The post Tom Stoppard Made a Spectacle of History appeared first on The Atlantic.