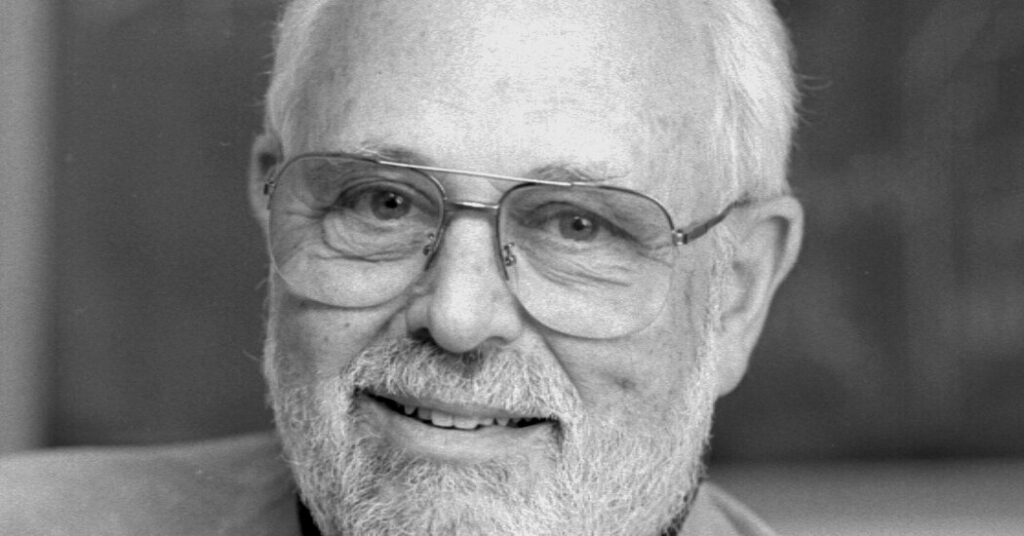

Kai T. Erikson, a sociologist who examined the aftermaths of floods, nuclear accidents, hurricanes and chemical spills to illustrate how disasters damage what he called the “tissues of communal life,” inflicting collective trauma that can outlast physical wounds, died on Nov. 11 in Hamden, Conn. He was 94.

His death, at a retirement home, was announced by Yale University, where he taught from 1966 to 2000.

Professor Erikson worked in the academic shadow of his father, the renowned psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, a Sigmund Freud disciple whose psychosocial development theory described a series of internal psychological crises that individuals face throughout their lives.

Aiming his own analytical lens outward, Professor Erikson probed the social and cultural trauma that is visually imperceptible after natural and man-made disasters, traveling so frequently to far-flung calamities that The Times of London called him “Professor Catastrophe From America.”

“Collective trauma works its way slowly into the awareness of those who suffer from it, so it does not have the quality of suddenness usually associated with ‘trauma,’” he wrote in “The Sociologist’s Eye: Reflections on Social Life” (2017). “But it is a form of shock all the same, a gradual recognition that the community no longer exists as a source of support or solace.”

Professor Erikson became interested in disasters by accident.

In 1973, he received a call out of the blue from a lawyer representing residents of Buffalo Creek, W.Va., a coal mining community where a dam had failed, unleashing 132 million gallons of thick black liquid that gushed through a narrow mountain hollow in waves 20 feet high. More than 100 people died. Thousands were left homeless.

The lawyer asked Professor Erikson if he knew a graduate student who might be willing to spend a semester studying the aftermath. “I told him over the phone that I could make a more informed recommendation if I saw the site myself,” Professor Erikson wrote.

After a few hours looking around Buffalo Creek, he took the job.

“I had never seen or even imagined anything remotely like that — desolate, dark, a scene of such heavy, muted pain that I have a hard time finding words to capture it decades later,” he wrote. “I was drawn to the place as if by a compulsion.”

Professor Erikson spent more than a year interviewing survivors, reviewing legal depositions, attending community meetings and observing daily life as residents struggled to rebuild their homes and their way of living.

He detailed their struggles in “Everything in Its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood” (1976), a mix of social science, narrative journalism and oral history. It was a finalist for the National Book Award in the contemporary thought category.

“Social scientists will, I hope, take note of the vitality and creativity of which their discipline is capable,” the author and political activist Michael Harrington wrote in The New York Times Book Review. “Nonacademic readers will encounter an exciting, enriching book.” He called it “a triumph of contemporary understanding.”

In the book, Professor Erikson let Buffalo Creek residents speak in their own voices, rather than paraphrasing them in academic jargon.

“The flood in its own way destroyed my past in the mental sense,” one said. “I knew everybody in the area. That’s where I lived, and that’s what I called home. And I can’t go back there anymore. I can’t even think of it. I have no past.”

To Professor Erikson, the physical damage and psychological displacement amounted to a “loss of flesh” — an acute trauma that becomes an ongoing state of mind, with permanent feelings of despair, anguish and emptiness.

“When the people of Buffalo Creek stood there and watched their possessions crash down the hollow, they were watching a part of themselves die,” he wrote. “To lose a home or the sum of one’s belongings is to lose evidence as to who one is and where one belongs in the world.”

Over the next 40 years, Professor Erikson traveled the world to embed himself in the aftermath of catastrophic events — a mercury spill in Ontario, the nuclear reactor accident in Three Mile Island, Pa., the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska the flooded streets of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and other tragedies.

Professor Erikson’s instinct to immerse himself in the places he wrote about was a throwback to the early days of sociology, when research was grounded in lived experience rather than the quantitative statistics and technical theory that pervades the field today.

“He was concerned with broad problems and big ideas, and he wrote about them beautifully,” Jeffrey Alexander, a sociologist at Yale, said in an interview. “You learn a lot about social order when it is very abruptly and visibly destroyed. You understand what really ties society together.”

Professor Erikson often testified in court on behalf of victims.

“Legend has it that his powerful presence and voice became so well-known and feared by opposing counsel that once, when he was seen to enter a courtroom for the defense unannounced, the other side immediately settled,” Yale said in announcing his death.

Kai Theodor Homburger was born on Feb. 12, 1931, in Vienna, Austria, to Erik and Joan (Serson) Homburger.

After the family immigrated to the United States in the early 1930s, Kai was reportedly taunted at school and called “Hamburger” by other students. His parents decided to change their last name.

Kai was studying sociology at Reed College in Portland when his father’s best-known book, “Childhood and Society,” was published in 1950. After graduating in 1953, he received his master’s degree and doctorate from the University of Chicago.

With an interest in field work, he spent several months immersing himself in a Polish community in South Chicago.

“That experience of the ‘feel of the streets’ made a deep impression on me, and it played a far greater role than I realized at the time in influencing my sense of what ‘social life’ really is and how one might go about studying it,” he wrote in “The Sociologist’s Eye.”

Before turning to disasters, he wrote “Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance” (1966), examining how deviant behavior “can sometimes be a valuable resource in society, providing a point of contrast, necessary for the maintenance of a coherent social order.”

Professor Erikson married Joanna Slivka in 1961. She survives him, along with their sons, Keith and Christopher Erikson; their daughter, Sue Erikson Bloland; and four grandchildren.

At Yale, Professor Erikson was to his admirers a lot like the inspirational teacher played by Robin Williams in the 1989 movie “Dead Poets Society” — though he wasn’t given to spouting poetry while standing on desks.

His former student, the author and political satirist Christopher Buckley, remembered him in an interview as the “Pied Piper.”

“We started a cult of Kai Erikson without him really knowing it,” Mr. Buckley said, recalling how he and his roommates, the future New York Times journalists Michiko Kakutani and John Tierney, went so far as to tape his discarded cigarette butts to their refrigerator.

They even staged a festival in his honor on their front lawn.

“It was just a funny concept that Kai Erikson was a god,” Mr. Buckley said, “and yet he was also this humble professor.”

The post Kai Erikson, Sociologist Who Probed Invisible Scars of Disasters, Dies at 94 appeared first on New York Times.