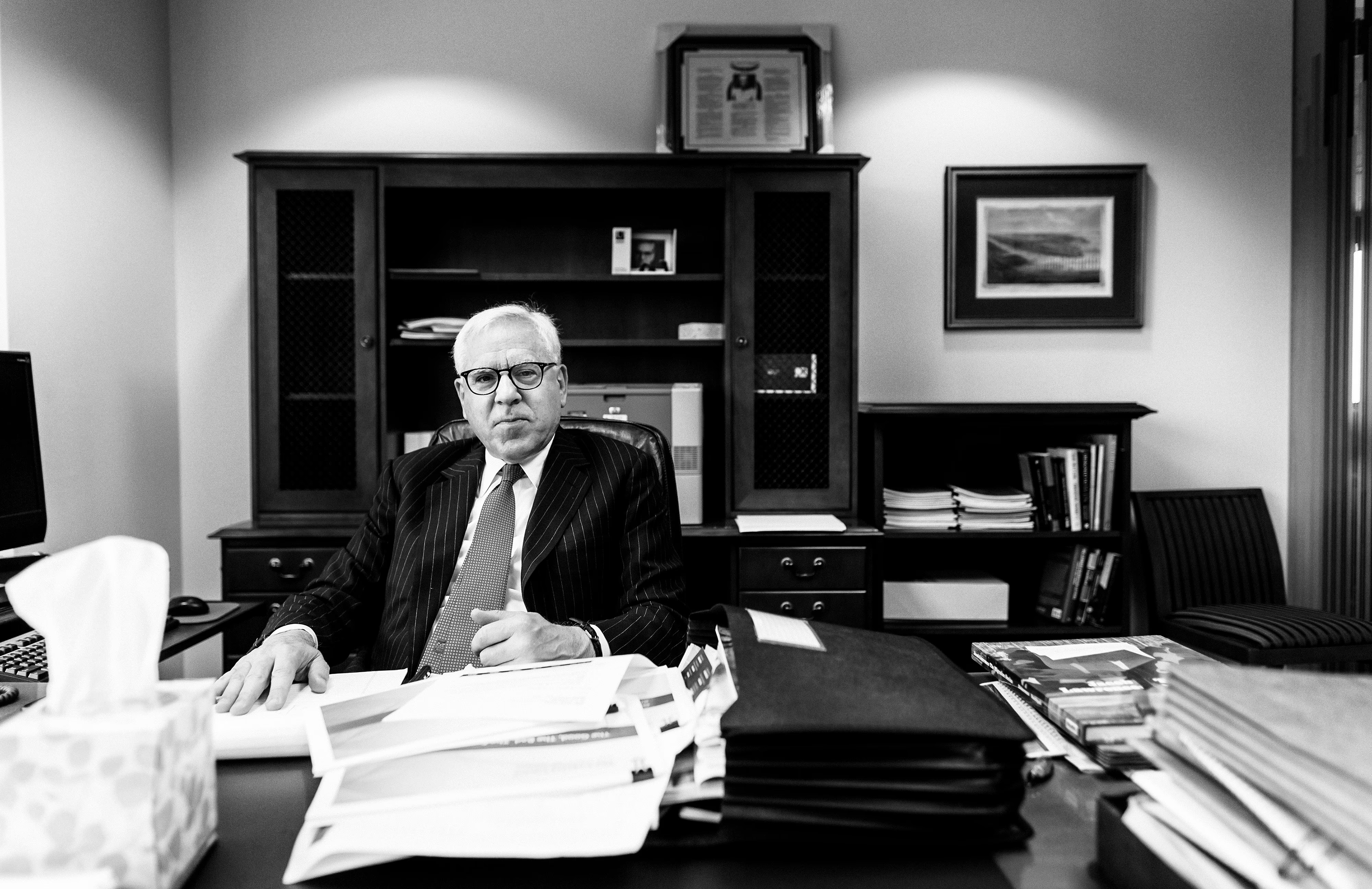

David Rubenstein, the billionaire investor and philanthropist, sat at a handsome marble table in a handsome conference room in one of the many handsome offices of the Carlyle Group, the global investment firm he co-founded, discussing a bit of personal unpleasantness.

Several weeks earlier, Donald Trump had fired him as the chair of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Rubenstein chairs many elite institutions, but the Kennedy Center might be seen as the capstone of his résumé. Explaining his decision, Trump had posted on Truth Social that Rubenstein did not “share our Vision for a Golden Age in Arts and Culture.” The president announced that the “amazing” new chair of the center would instead be one “DONALD J. TRUMP.”

Rubenstein, who is not accustomed to being fired, at first deflected my questions with gin-dry self-deprecation: “I’m the first person to be fired by a president and succeeded by one.” But the firing stung. Rubenstein has, for decades, converted his extraordinary wealth into soft power, cultivating an ostensibly apolitical brand. He calls himself a practitioner of “patriotic philanthropy,” with a stated mission to remind Americans of their heritage and history in service of a strengthened democracy. As part of that mission, Rubenstein has given away more than $1 billion. His name is stamped all over the Washington region.

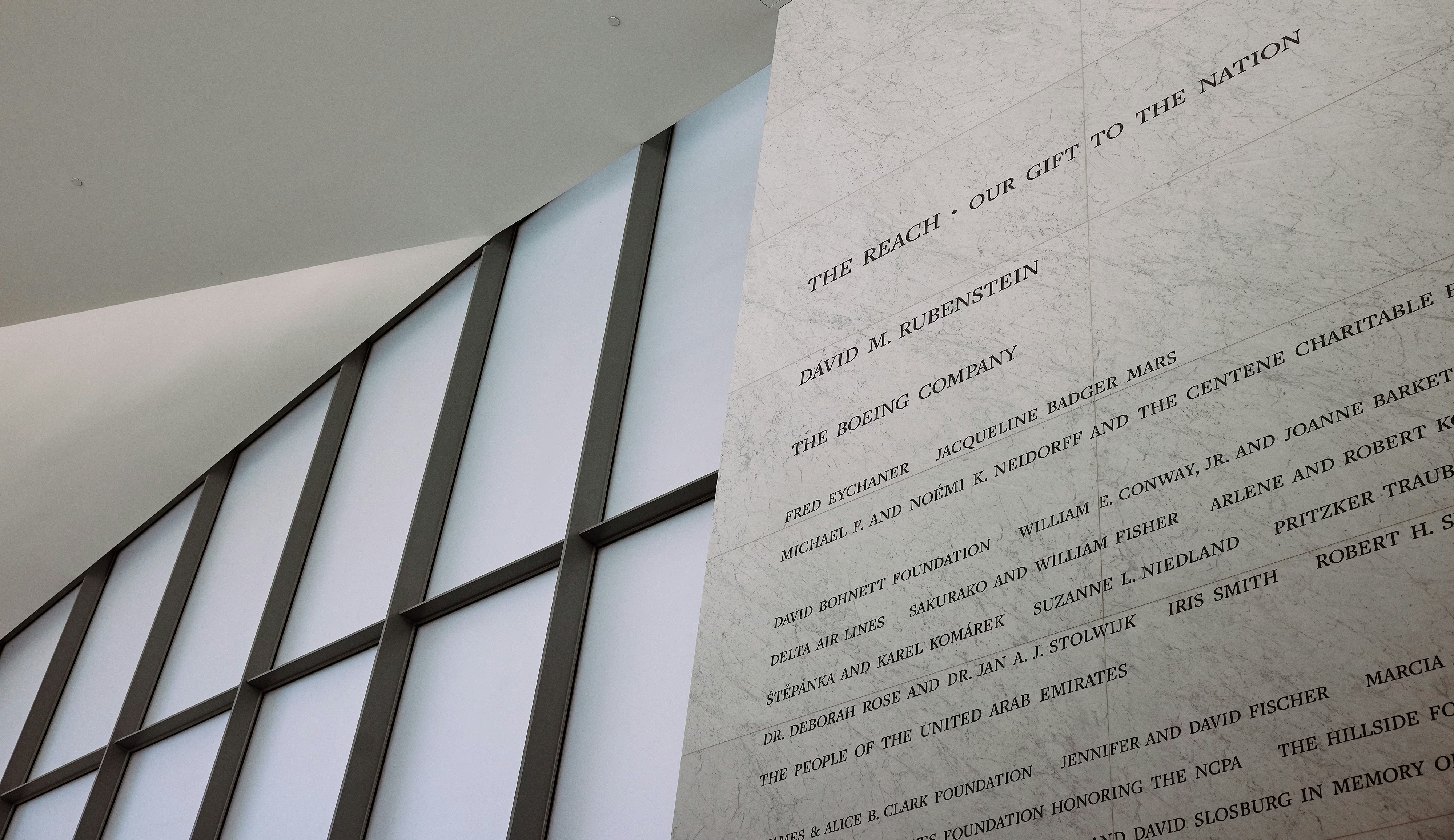

The homestead of Thomas Jefferson has a David M. Rubenstein Visitor Center; George Washington’s estate benefited from a $10 million donation to its library. Rubenstein gave the National Museum of African American History and Culture $10 million, along with a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation that is displayed in the David M. Rubenstein History Galleries. He donated in excess of $100 million to the Kennedy Center, where he oversaw construction of a large annex. When the giant pandas Bao Li and Qing Bao arrived at the National Zoo last autumn by airplane from Chengdu, China, they set out to explore their new digs: the David M. Rubenstein Family Giant Panda Habitat. When an earthquake damaged the Washington Monument in 2011, Rubenstein kicked in $10 million to help pay for repairs.

I first interviewed Rubenstein months before the 2024 presidential election. Back then, he was confident that he could manage his relationship with Trump if he were to win, as Rubenstein had after Trump’s 2016 victory. The two men regarded each other as friends—sort of. In 2014, he interviewed Trump onstage at the Economic Club of Washington (“When David calls, I say yes,” Trump told the crowd). The Trump of 2025, however, is a different fellow than the Trump of 2017. Institutions and norms at least tolerated by previous Republican presidents exert no hold on him, nor do the genteel mechanisms of soft power that have run Washington for years. The mere existence of a complex of arts, history, and the old Washington establishment itself, all sitting somewhere just outside the official D.C. bureaucracy, seems to rankle Trump—especially when the leaders of those organizations decline to declare fealty to him. All of this set Rubenstein on an unintended collision course with Trump.

Besides, Rubenstein told me, only half joking, having “a billion dollars is not what it used to be.” Rubenstein did not, in the fashion of Bill Gates, build a paradigm-shifting computer-operating system. He did not, as Steve Jobs did, create an artful, culture-shifting technology firm. Nor did he, like Jeff Bezos, construct a consumer behemoth. The lifework of private-equity barons offers less social utility. They accelerate the financialization of the world economy, boost the performance of public pension funds and college endowments, and produce fabled wealth for themselves and the exceedingly comfortable. Along the way, their work can sometimes make life measurably more painful for families on the lower end of the income scale.

Rubenstein, who is 76, has studied the actuarial tables and knows his end is an approaching train. He remains a co-chair of Carlyle and still travels the world raising money and speaking at lavish investor conferences. He drinks neither alcohol nor coffee, plays no golf, and harbors no desire to retire and work on a meditative memoir.

Trump has signaled—much as Vladimir Putin did to his own oligarchs—that even the wealthiest would be wise to bend a knee. He’s given the comfortable class a clear look at what he can do to those who refuse to do his bidding. Trump has batted around Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell—a former Carlyle partner and a friend of Rubenstein—like a piñata for refusing to cut interest rates. Trump has ended federal contributions to PBS—Rubenstein is one of its largest individual donors, and has hosted two shows on the network. Trump has similarly attacked the Smithsonian, complaining that it’s out of control and overly focused on “how bad Slavery was.” He has demanded a “comprehensive internal review” of its exhibitions.

If there was a single way to describe Trump’s institutional targets in the first year of his second term, it might be “David Rubenstein’s Rolodex.” What had long been Rubenstein’s instrument of immense power and influence is now a liability.

[From the June 2025 issue: Ashley Parker and Michael Scherer on Donald Trump’s return to power]

Rubenstein grew up in what he calls a “Jewish ghetto” in deeply segregated 1950s Baltimore. He recalls thinking as a child that everyone in the world was Jewish; he told me he was 13 when he realized that there were far more goyim. His grandfather had come to the United States in the early 20th century at the age of 10, fleeing anti-Semitic pogroms in Ukraine. (An Ellis Island clerk, he says, changed the family surname from Rubensplash to Rubenstein.) His father served in World War II and worked as a postal clerk, and his mother worked in a dress shop.

I asked if Rubenstein discerned an arc to his life, some hint or premonition of great riches and influence to come. He wagged his head no. He was not a good athlete; he peaked in Little League. He insisted to me that he wasn’t intellectually gifted, despite having skipped eighth grade and graduated high school at 16 years old. And socially, well, “I wouldn’t say that the girls in the Baltimore Jewish community were just saying … ‘This guy is so handsome, charming. He’s wealthy. He’s going to be famous.’ No, there was none of that.” He gave me a palms-up shrug and made rare eye contact: “It was a tortoise-and-the-hare thing.”

Rubenstein did, however, feel a skin-afire urgency for a life that was more than the post office. He wanted to break out, though how and to what end was a mystery. He attended Duke University, where he studied political science, followed by law school on full scholarship at the University of Chicago. Rubenstein landed at the white-shoe law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, where he worked for two years in the ’70s. There he befriended Ted Sorensen, a former speechwriter for President John F. Kennedy, who became his mentor.

Being a lawyer was not, he came to realize, his calling. He told Sorensen several times that he yearned to work in politics and public policy. His ambition was not workaday; Rubenstein said that he had the White House in his sights. Sorensen made a few phone calls, and at age 25, Rubenstein became chief counsel to the charismatic senator Birch Bayh, a Democrat from Indiana. Bayh entered the 1976 Democratic presidential primary with high hopes but flamed out, laid low in part by his support for abortion rights. Rubenstein dialed Sorenson again. “Well, do you have any more candidates that I might work for?” he asked. Sorensen put Rubenstein in touch with a powerful lobbyist, who in turn connected him with a southern Democratic presidential candidate who needed staff. Rubenstein signed on. “I didn’t know Carter from a hole in the wall,” he told me. “I can’t say I had a compelling desire to work for Jimmy Carter.”

Yet he would serve as a top deputy to Carter’s domestic-policy adviser, Stuart Eizenstat. He described himself as “not qualified, not experienced, but eager,” and he grew accustomed to walking into the Oval Office and talking with Carter. (He recalled that the president was “very smart,” a taskmaster who hated split infinitives. “No one would say he had a great sense of humor,” he said.) Rubenstein was a bundle of nervous energy. He ate out of White House vending machines and walked about hollow-eyed from lack of sleep.

There is an oddity here. One can talk with Rubenstein for hours without hearing him express sharp-edged political beliefs. He worked for Democrats, but even today he rarely mentions the issues that moved him.

Carter lost to Ronald Reagan in 1980. Rubenstein was a lonely Democrat in a world turned conservative Republican. Power brokers stopped returning his phone calls. He joined a midsize law firm and became a partner doing what Washington lawyers do: selling access. At this point he was making, “by normal human standards, a fairly good income,” he told me. He would soon marry his wife and have three children. He saw the shape of his future: Perhaps former Vice President Walter Mondale would win the presidency in 1984 and he’d get back into government. Maybe by the time I’m 70 years old, he recalled thinking, I will be deputy secretary of transportation or something.

That reverie held no kick for him. Rubenstein had tired of playing the mercenary. And, he told me, “nobody thought I was a great lawyer.” It was the Roaring ’80s on Wall Street; he saw peers from the political world, men lacking anything like his IQ, getting wealthy. One morning, he read that former Treasury Secretary William Simon had invested $330,000 in a greeting-card company and made nearly $70 million in 18 months. Why not hang out a shingle, he said to himself, and try my hand in this world? Rubenstein quit his law firm and, with three partners and fundraising help from the financier Edward Mathias, obtained $5 million in seed capital to launch Carlyle in 1987; the founders named the company after the historic New York hotel to confer a touch of class. The game to which these men sought entry was known as private equity. Most major private-equity funds sat in financial capitals: New York, London, and Hong Kong. Carlyle’s headquarters faced Pennsylvania Avenue, in between the White House and the Capitol. “If I had moved to New York to do it, nobody would have taken me seriously,” Rubenstein told me. “I didn’t have investment-banking experience, and all the other private-equity firms have been started by investment bankers.”

The sector was taking flight, and its pioneers made no pretense of high-minded pursuit. The goal was to get rich and richer still, and their theory of the hunt was straightforward: Find companies that had grown fat, put up the most modest of stakes—sometimes as little as 1 percent equity and no more than 5 percent of the asking price was ideal—and borrow the remainder against the value of the company. In other words, the prey would finance its own kill. Conduct a hostile takeover, fire leaders and institute layoffs, and streamline the newly debt-burdened companies before selling them. Should these efforts fail and a company collapse, sell the assets.

But when the Carlyle boys tried their hand at identifying takeover targets, more experienced heads at other companies scoffed at them. Who were these novices? Rubenstein acknowledged the truth in that. “I thought I’d build a little teeny investment firm,” he told me. “Maybe we’d do a leveraged buyout—as soon as I figured out what a leveraged buyout was.”

They had no real plan. Then they went to Alaska.

Not long ago, I found myself in a coffee shop in Anchorage, listening as an ornery old attorney, Donald Craig Mitchell, talked of impecunious Native tribes, tax-loophole wizardry, and ambitious D.C. influence peddlers on the make.

Alaska is crucial to understanding the Rubenstein origin story. In the early ’70s, Congress and President Richard Nixon created the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which aimed to settle tribal land claims by transferring 44 million acres of land and nearly $1 billion to Alaska Natives. Native-run corporations would own and administer mineral, fishing, and timber rights on a for-profit basis, employing thousands of Natives and lifting entire communities out of poverty. That was the theory, anyway.

The reality was messier, and the plan wildly ambitious. At the time, most Alaska Natives lived deep in the bush. Just 14 percent had completed high school and 1 percent had graduated college. The act pitched tribes into a crash Westernization. By the mid-’80s, several Native-run corporations teetered near insolvency. Alaska’s powerful Senator Ted Stevens, a Republican, stepped in to help. He created a tax loophole, which he assured the Senate would not prove terribly costly, and attached it to a 1986 tax bill. (Stevens had reeled in so many federal dollars that Alaskans jokingly referred to him as the state’s largest industry.) The loophole allowed Alaska Native corporations to sell losses on lumber, mining, and fishing to large American corporations seeking to reduce their tax liability—a potential lifeline for the Native corporations and a profitable possibility for middlemen who understood tax law. You see where this is going?

Rubenstein and his partners in the fledgling Carlyle firm were struggling to make their way in a financial world they only half understood. But they had a splendid sense of how politics and backdoor decision making worked in D.C. One day, Stephen Norris, a co-founder of Carlyle, told Rubenstein of the Alaska loophole, a situation that was practically tailor-made for the firm’s expertise. Rubenstein, then 38, took notes. This, he figured, might be their break.

The Alaska loophole gave birth to what those in Washington business circles called the “Great Eskimo Tax Scam.” It was akin to sounding a dinner bell for D.C. lawyers. Rubenstein dialed tribal leaders and lobbyists affiliated with the Native corporations and promised that he could make them lots of money—in exchange for a cut of the action. He and Norris recruited corporations in search of tax losses, flying the executives to Washington and lodging them at posh hotels. Many of the Native leaders Rubenstein worked with have passed away, but I found a long-retired Native businessman who shared his recollection on condition of anonymity. Rubenstein, he told me, did not talk of the beauty of Alaska’s forests and fjords. Nor did he make much eye contact. I will make you millions, he said, and I will work seven days a week. It was, this man recalled, a disarmingly effective spiel.

In less than a year, Rubenstein and Norris bundled and sold more than $1 billion worth of tax losses by tribal corporations to American companies. For their service, Rubenstein and Norris charged a 1 percent fee and walked away with at least $10 million. With that, Rubenstein knew that he could compete in the world of finance.

The Alaska sales job clarified something else for him too. He was neither an economics wunderkind nor a hawkeyed stock picker. Improbably, however, this man who so often fixed his eyes on his shoes during conversation discovered he could persuade wealthy people to part with investment capital. Soon he was boarding airplane after airplane, traveling hundreds of days each year, wooing politicians and pension-fund officials, Texas oil barons and Middle Eastern emirs. Painstaking preparation preceded each conversation, whether in corporate offices in Switzerland, a swank restaurant in Singapore, or a mansion overlooking the Persian Gulf. “I made myself into a fundraiser, which was a little incongruous, because I wasn’t an outgoing personality,” Rubenstein told me. “You just have to steel your courage up.”

In 1989, Rubenstein recruited Frank Carlucci to be Carlyle’s managing director. A short and intense charmer, Carlucci had spent more than a decade in the foreign service, then served as deputy CIA director in the Carter administration and defense secretary in the Reagan administration. Finance types at other firms clucked dismissively about Carlucci’s lack of investment experience. Rubenstein waved them off.

The late ’80s were a time of disarray in the armaments sector, and private equity thrives in disarray. As defense secretary, Carlucci had reorganized the Pentagon’s contract armament-procurement system. He knew the right people: the generals, the defense undersecretaries, and staffers who made the gears of the trillion-dollar defense world move. The Cold War was ending, and corporations were putting defense divisions up for sale. Carlyle wanted to avoid the markup associated with auctions run by Wall Street firms; a discreet phone call from Carlucci to a defense-contractor CEO was preferable.

Private-equity firms of the era gloried in excess. Greed was good, and publicity reified status. Rubenstein speaks of that time with the dispassionate and distancing tones of an anthropologist. It “was not, you know, ‘Let’s worry about DEI,’” he told me. Nor was it “‘Let’s make sure we pay all our taxes; we’re very good on environment; and let’s make sure we don’t lose any jobs, because we don’t want people to lose their livelihood.’” He shook his head. “The zeitgeist was ‘What is the highest internal rate of return we could get?’”

In 1993, a reporter slipped behind the Carlyle curtain as the company was growing rapidly. The New Republic writer Michael Lewis, who later wrote the best-sellers Moneyball and The Big Short, talked with Rubenstein and Carlucci at length for an article titled “The Access Capitalists.” Rubenstein came off as an awkward but connected man who understood a world fueled by the currency of access. To call him an old-fashioned entrepreneur was, Lewis wrote, “one of those half-truths that contains even less truth than a lie.” Rubenstein and his partners still talk about how much that New Republic piece stung.

But Lewis depicted the firm as immensely profitable, and that was catnip for D.C.’s wealthy. “If you’re an investor, you want access,” a Carlyle co-founder who requested anonymity told me. “Suddenly everyone wanted to talk with us.”

The ’90s became a time of explosive growth in Carlyle’s defense spending. Carlyle’s $850 million purchase of United Defense, which manufactured tanks, artillery, naval guns, and missile launchers, was particularly fruitful. United Defense reeled in $5.8 billion in contracts from the Pentagon. When Carlyle fully exited the company, in 2004, it had made more than a $1 billion in profit. By 2000, the collective value of defense companies in Carlyle’s portfolio rivaled that of Raytheon and General Dynamics.

Meanwhile, Rubenstein kept hiring prominent Republicans, and not only from the defense sector. In 1993, he brought on a double bill from George H. W. Bush’s administration: Secretary of State James Baker—a Princeton classmate of Carlucci—and Office of Management and Budget Director Richard Darman. During Bush’s term, Rubenstein had put his son George W., on the board of a Carlyle subsidiary, too. That proved to be a misstep: Rubenstein told investors that the son had a taste for off-color jokes and no evident feel for private equity. Finally, in 1998, Carlyle added the former president, Bush himself, as an adviser. “I recruited people who I thought could get their calls returned,” Rubenstein told me.

Those Rubenstein brought along made out well. By 2001, Baker may have held as much as $180 million in equity in the firm.

To ask Rubenstein about the value of Carlyle’s high-profile hires is to observe a rhetorical two-step. These men were door knockers, he said, the shiny objects meant to attract attention. A potential client might turn down a dinner invitation to talk out investment opportunities with David Rubenstein, he told me, but they’d show up for Jim Baker: “I’m paying these guys basically to speak at the dinner or lunch.” As wealthy guests appeared, Rubenstein would move in, shaking hands, persuading them to invest in Carlyle.

There was more to it. Carlucci’s phone calls led to the purchase of companies. After he left office, the elder President Bush helped Carlyle win a battle to acquire a Korean bank. When Rubenstein flew to the Middle East to raise money, he invited Baker to tag along. “Because I’m Jewish, I didn’t think I should go,” he told me. But when he expressed his reservations to Baker, Baker gave him a look as if to suggest he was a naif. “It’s not a problem that you’re Jewish,” Baker replied. (Rubenstein since has come to see a certain advantage to being Jewish in that region. As he put it, “People in the Middle East thought: ‘Jews are smart. They know how to manage money.’”)

That cozy world changed on September 11. As the airliners crashed into the World Trade Center towers, Carlyle was running an investor conference at the Ritz-Carlton in Washington, D.C. In attendance were members of the bin Laden family, including Shafiq bin Laden, an estranged half-brother of Osama. This was unfortunate timing for both Carlyle and the bin Laden family, which hurriedly liquidated its holdings in a Carlyle fund that invested in buyouts of military and aerospace companies.

Within a few years, Carlyle’s challenges began to cascade. Anti-war demonstrators picketed. Congress asked tough questions. The Economist magazine opined that Carlyle “gives capitalism a bad name.” The founders felt exposed. “We were heavily criticized for having been part of the ‘war machine,’” Rubenstein told me. He gave a slight shrug. “If you live by the sword, you die by the sword.”

The life of a private-equity titan is wonderfully remunerative and unfailingly unsentimental; he knew what he had to do. In March 2005, as body counts in Iraq mounted, Rubenstein and a partner, Daniel A. D’Aniello, walked into Baker’s office.

The former secretary of state eyed the Carlyle founders scuffling and staring at their shoes. He chuckled. He recognized his end. “You guys!” he said loudly to Rubenstein. “You need to separate from me. I’m a big boy, I get that.”

Carlucci had retired two years earlier. Rubenstein turned his attention to George H. W. Bush. He was fond of Bush, and regarded him as a smart man of impeccable manners. “It was awkward,” he allowed.

Rubenstein need not have worried. The former president was scion of a wealthy WASP family and a former intelligence chieftain, and reacted with no less sangfroid than Baker. This was the business these men had chosen. “Bush said to us, ‘Look, I know the war is going south and you’re getting blamed. Cut me loose,’” Rubenstein recalled.

Since 2004, Carlyle has pivoted away from defense—but it still runs by the logic of access capitalism. Carlyle does private lending and holds stakes in aerospace companies, luxury housing, health care, oil fields, natural-gas pipelines. It has owned and sold majority stakes in Hertz; Dunkin’ Brands; Cogentrix Energy, an American power generator; and Booz Allen Hamilton. It has purchased significant tracts of real estate, extended credit to builders, and moved into the insurance sector. Carlyle took a minority stake in McDonald’s China in 2017; it sold that for $1.8 billion in 2023. It helped finance and lead a renovation of John F. Kennedy International Airport, creating 10,000 jobs.

[Roge Karma: The secretive industry devouring the U.S. economy]

But not all is well. Interest rates have climbed, the sector has grown crowded, and as more and more private-equity firms compete to buy companies, prices go up and profit margins are squeezed. Private-equity firms hold more than $3 trillion worth of unsold firms; investors cannot see returns until these sales go through. “Private equity has struggled a bit,” Rubenstein told me, adding that growth has slowed noticeably. The biggest firms resemble great white sharks, swimming in ceaseless search of yield and profit. Although they have ventured into obscure or unlikely areas, the weight of their deals has tended to fall heavily on working-class Americans. As Brendan Ballou wrote in his book, Plunder, private-equity firms were responsible for 600,000 jobs lost over the past decade in the retail sector alone.

Mobile-home parks offer an instructive case. Twenty million working-class and poor Americans live in trailer parks, the biggest pool of nonsubsidized affordable housing in the nation. Family operators traditionally owned these parks, but private-equity firms have piled in, seeing opportunity in a national housing shortage. Blackstone, Apollo, and Carlyle are among the 23 private-equity firms that now own more than 1,800 mobile-home parks with 377,000 lots, or about 4 percent of all parks in the country.

Which, after a fashion, explains how I found myself driving through the high desert and the Carson Mountains to Sparks, Nevada. I turned into the Sierra Royal Mobile Home Park on a razor-sharp morning and saw well-kept mobile homes with ornamental bushes and flowers. Jeanneil Marzan, a white-haired retiree, stood at her door. “We bought here because it was a nice, quiet community, and affordable,” she told me.

Mobile-home economics are straightforward: Marzan owns her home and rents the land for about $900 a month from Sierra Royal. But in 2022, when Carlyle purchased the mobile park, monthly land rents for new tenants rose to $1,010. That set a tough standard for new renters and drove down buyer demand.

“It was like ice water thrown on us,” Marzan said.

“Carlyle wants money we don’t have,” Roger George, one of her neighbors, told me.

Some days later, I talked mobile homes with Rubenstein, who insisted that Carlyle seeks to improve mobile parks and discusses plans beforehand with tenant groups. (No tenant I interviewed at the Sierra Royal recalled such a consultation.) “People are living in mobile homes not because, I suspect, they love mobile homes but because that’s what they can afford,” Rubenstein told me.

A spokesperson suggested I examine Plaza Del Rey, a mobile-home park in Sunnyvale, California. Carlyle purchased this working-class pocket of Silicon Valley 10 years ago, and he said “it worked out really well for everyone.” But when I exchanged emails with a Plaza Del Rey tenant, Fred Kameda, I heard a different story. He moved there in 2011. When Carlyle took over, he said, it sharply increased costs for new residents, doubling rents in five years. “The land-rent increases had the immediate impact of reducing the sales price of our home,” Kameda said. “Our mortgages are underwater and our homes unsellable.” Carlyle paid $150 million to acquire Plaza Del Rey in 2015 and sold it four years later for $237 million.

Carlyle’s foray into nursing homes raised more troubling questions. In 2007, the firm purchased Manor Care, one of the nation’s largest nursing-home chains, for $6.3 billion. At the time, critics cautioned that Carlyle did not appreciate the patients’ vulnerability, and warned about the consequences of trying to juice the profit margins. But Carlyle’s analysts exuded cockiness. “Manor Care is poised to become an even stronger health care provider under Carlyle’s ownership,” the firm stated in a 2007 release.

Carlyle borrowed $4.8 billion and put that on Manor Care’s ledger. There was a sale leaseback. Carlyle paid itself handsomely to manage the nursing homes, but the nursing-home chain began to leak money. A 2018 Washington Post investigation found that patient care crashed after Carlyle’s takeover; inspectors saw patients with bedsores and sitting in urine, and residents and their families consistently reported that staffing was inadequate. In March 2018, the chain filed for bankruptcy and Carlyle slipped away. (Carlyle told The Washington Post at the time that it had only reduced administrative—not nursing—costs, and attributed Manor Care’s financial troubles to a decline in federal Medicare spending. A spokesperson told The Atlantic that Carlyle had “exited the investment in 2018” and was no longer involved with the chain.)

Manor Care represented a significant investment and a large embarrassment for Rubenstein and Carlyle. How, I wondered, did a nursing-home chain with tens of thousands of employees deteriorate so markedly while owned by one of the globe’s wealthiest private-equity firms? “Nursing homes is a difficult business, right?” Rubenstein replied.

Right.

“It’s pretty easy to say, Well, 20 percent of your people died,” he continued. “But, you know, they get into the nursing home when they’re 90 years old. They’re probably going to die at some point.” Going forward, he said, Carlyle will avoid investing in nursing homes. “It’s hard to convince people that you’re adding a lot of value,” he said. That was perhaps especially the case with respect to Manor Care, where the reverse was true.

Rubenstein sat in his office on a sultry summer day at Camden Yards—he had recently purchased his hometown Orioles for $1.725 billion—as our conversation turned to his wealth. He’d presented himself to me as a run-of-the-mill billionaire, recounting deals missed and titans with fortunes that eclipsed his own.

Rubenstein’s not that rich, by billionaire standards. The nation has some 1,000 billionaires, and his pile is a fraction of that of his wealthiest peers in private equity, a fact that has not escaped his notice. As Rubenstein had noted to me, having $1 billion is not what it used to be. But he also acknowledged that he is fabulously wealthy—he is at least that self-aware.

Rubenstein knows that many Americans view his sector as a fixed casino, and hinted at slightly bruised feelings. “You can always make jokes about private equity,” Rubenstein told me. “People think, as Balzac said, that behind every great fortune there’s a crime. If you’ve done something to make a lot of money, you must have done something wrong somewhere.” But where was the crime, Rubenstein continued, in accumulating piles of riches for yourself and your investors if, along the way, you also delivered great returns to public-employee-pension funds and college endowments and invested in companies that create jobs?

Rubenstein tutored me in the mathematics of private-equity profit extraction. His analysts target underutilized market sectors, whether a gas pipeline in Alaska or a Mumbai-based life-insurance company. It fell to him to persuade trustees of pension funds and managers of university endowments to hand over investment dollars. (He made many phone calls and several trips to California to woo trustees of Calpers, the agency that manages public retirement funds in that state. It’s now a major investor in Carlyle, with billions of dollars in various funds.) Private-equity services do not come cheap. Although management fees have fallen recently, the standard industry charge for years was 2 percent of total capital annually and 20 percent of profits. The legendary returns make it all worthwhile.

Or not. Ludovic Phalippou, an economics professor at Oxford and a critic of private equity, has argued that when fees are factored in, private-equity returns differ not much from those of stock funds. Other prominent analysts take an even more pessimistic view; Morningstar, a well-regarded fund-rating agency, cautions that of the 14 private-equity-focused funds launched in 2022 or earlier, 11 have underperformed the S&P 500 since their inception, some “by a lot.” To Phalippou, private equity is terrific at creating wealth—for its founders. One speculates he is not a favored guest at private-equity soirees. (Private-equity economists argue that their companies investments cannot be measured by comparing them year over year to, say, stock-index funds. The sale of equity investments are carefully timed, they argue, and they note that many sophisticated investors apparently agree with them).

I asked Rubenstein whether the private-equity fee structure is a touch avaricious. He shrugged. “Trying to defend making high rates of return and making 20 percent of the profits is not easy to do,” he replied evenly. I looked at him, puzzled, and he steadily returned my gaze.

Private equity charges what it does because it can. And private equity, whatever its capitalist digestive problems, continues to disgorge billionaires. From 2005 to 2020, private-equity billionaires have multiplied from three to 22; Phalippou calls the sector a “billionaire factory.” To Rubenstein’s repeated point, some of his peers—Leon Black, Henry Kravis, and Stephen Schwarzman leap to mind—have a net worth far greater than his own.

Central to Rubenstein’s sense of himself is an inchoate desire to outstrive peers, in business, in philanthropy, in public fame. Without a therapist—he has never seen one, he told me—he cannot explain this compulsion. Age, however, has rendered him curious about its genesis.

He invited me to engage in a speculative exercise. Who was first in your high-school class? Do you remember? he asked in a manner that suggested he had forgotten his answer. “There are many people who had incredible résumés that I would have died for, and now they’re retired. They’re not doing much. They’ve lost their drive. It’s strange how the world works.”

He mentioned a friend in Chicago, a wealthy man diagnosed with ALS, the deadly neurodegenerative disease. He also told me that, a few days earlier, then–Georgetown University President John DeGioia, another acquaintance and eight years his junior, had suffered a stroke during a meeting. (DeGioia has since stepped down.) Rubenstein told me he peruses newspaper obituaries with careful attention to detail. “I read the obituaries to see whether people younger than I died and why they might have died,” he said. “I’m at an age where a lot of your friends die.”

“How did I get lucky?” he asked.

There was his unspoken chaser: How long will his luck hold? Rubenstein has spent much of his adult life in black SUVs and private airports and mansions and princely restaurants, in conversations with sheikhs, presidents, and managers of sovereign wealth funds. He has spent 250 days a year on the road, often as the lone passenger—he prefers solitude—on his Gulfstream jet. He rarely if ever watches movies on the plane, preferring to read the books and newspapers piled at his feet or study numbers and rehearse his pitches. As he joked (I think) on a recent business podcast: “I told my family, ‘Bury me in my airplane.’ I’m never so happy as when I’m in my plane. I can call people or not call people. They can’t reach me easily. I can watch TV; I can sleep.” A boulder outside his mansion in Nantucket, where he rarely sleeps, is inscribed I’d rather be working.

“I want to get it done before I die,” he said of philanthropy and empire building. He calls it his “sprint to the finish.”

Rubenstein gave me a list of his friends and colleagues. All praised his intelligence and attentiveness. When I asked if Rubenstein ever called them to just chat, if they shared laughs over long dinners, they fell silent or shook their head.

Each year at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, James Gorman, the former Morgan Stanley chair who is now the chair of Disney, throws a big dinner, and Rubenstein joins him at the head table. “Some people feed off of moving constantly,” Gorman told me. “If you slowed David down, he’d slow very quickly. It’s like a fish that stops swimming. They stop and they die.”

Rubenstein told me once that he wondered whether his three children had inherited his obsessive drive. He has said that they grew up “reasonably wealthy.” (He had earned millions by the time his eldest daughter was in elementary school, and he was closing in on his first billion by the time she graduated college.) Too much comfort, he said, puts the children of the wealthy at a disadvantage. “You might have grown up spoiled, without the drive to achieve something,” he said.

As adults, his children, now ages 34, 37, and 40, followed Rubenstein into the family business, and although he’s signed a pledge to give away perhaps half of his fortune to charity, he’s also plowed millions—“modest amounts,” he calls the sum—into his children’s private-equity funds. He noted, a touch archly, that the kids have yet to produce quite the promised returns. His son, Andrew, is a co-founder of the venture-capital firm Shorewind Capital. His daughter Alexa Rachlin, after a stint at Goldman Sachs, works at Declaration Partners, which is anchored by Rubenstein. His younger daughter, Gabrielle, who co-founded Manna Tree Partners, seems to most embrace his work ethic. Years earlier, at a conference in Zurich, she offered a glimpse of what it was to labor in the shadow of an influential multibillionaire father. She spoke of embarking on an exhausting 323-day, 18-country fundraising tour that she halted only as COVID swept the globe in early 2020. “It really destroyed my microbiome,” she said at the conference. But “I earned my father’s trust. My father’s language is fundraising.”

There’s a decent chance today that if you are not in the finance industry, you know of Rubenstein less for his career in private equity than for his role as a benefactor: the halls and galleries, the placards on monuments, the board seats at elite nonprofits and universities. His philanthropy resembles the late-life turn of many famously wealthy men. Andrew Mellon established the National Gallery of Art. John Rockefeller gave away a large chunk of his fortune, equivalent to more than $10 billion in today’s dollars. Andrew Carnegie, the steel baron, divested himself of 90 percent of his wealth and built 2,509 libraries. Carnegie even marked himself as a sort of class traitor by celebrating progressive taxation: “By taxing estates heavily at death the state marks its condemnation of the selfish millionaire’s unworthy life.”

No such heresy escapes Rubenstein’s lips; he has no inner Bernie Sanders, and has defended the tax advantages that his class views as birthrights. He gives great sums to children’s health care and cancer research, but his passion is his own brand: patriotic philanthropy. He said that reminding people of America’s narrative arc strengthens American democracy. It’s also the case that his philanthropy reinforced his station—as an exemplar of Washington’s old establishment.

In return for his donations, Rubenstein has collected a blur of board memberships and chairmanships—the Kennedy Center, the National Gallery, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Brookings Institution. Celebrities surrounded him. He has stood with evident joy among presidents and first ladies, chatted with the comedian Billy Crystal, given awards to Bette Midler and Big Bird.

Rubenstein tended to the business of reputation building ever so carefully. He is averse to controversy and does not donate to political campaigns. But a man of wealth has many ways of rendering service to political patrons. He has several times turned his 13-acre Nantucket estate over to the Bidens. (George H. W. Bush and his wife have stayed there as well.)

This is an old sort of D.C. power projection. To wit, in the final days of his administration, Joe Biden awarded Rubenstein the Presidential Medal of Freedom. That could be read as status affirmed, another honor to be tucked into Rubenstein’s obit file, his sprint to the finish looking grand.

One observer was, however, not so impressed: Donald Trump, who, during his first term, was often stiffed by the sort of celebrities who surrounded Rubenstein. He watched Rubenstein, his maybe friend, aglow in a nest of Democrats, sitting on stage with Hillary Clinton and Alex Soros. Anna Wintour was there as well, and she had not put Melania, the first lady, on the cover of Vogue. The perceived slight, say those who know them, ate at Trump. Three weeks after Trump’s second inauguration, Rubenstein was out as chair of the Kennedy Center.

In one of my interviews with Rubenstein, in the conference room of a 32nd-floor Carlyle aerie in Manhattan, I asked whether Trump’s unsettling admixture of resentment, bullying, and retaliation threatened his legacy. This president is—Rubenstein paused and picked his word carefully—“unique.”

I looked at him. Was that all? What of Trump’s mercurial game with tariffs, the humiliation of foreign leaders, the masked men carrying out immigration arrests in schools and stores, the deportations without due process? What of Trump’s challenge to constitutional norms? Rubenstein, who fancies himself a lay historian of the American presidency, speculated that Trump might circumvent the law and run for a third term in 2028. “He feels he can be president longer,” he said. Amend the Constitution; “just stay there,” refuse to leave the White House at the end of his term; or run as vice president on a ticket with J. D. Vance so that Vance can resign upon their election, leaving Trump to take power again.

Rubenstein laid out these scenarios. And a few seconds of silence followed. The unspoken thought seemed to hang in the room: Don’t captains of finance have a duty, perhaps even an obligation, to speak up? “Right now, who in the business community is publicly saying, ‘You can’t be doing all the things you are doing’?” Rubenstein said after a while. “Nobody, nobody.”

Rubenstein sat for the first time this year on the committee of the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation that hands out the annual Profile in Courage Award. Past award winners have included the civil-rights legend John Lewis, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, and Senator John McCain. In these perilous times, Rubenstein said, the board had trouble finding someone “who actually has the courage right now to deserve the Profiles in Courage award.” Too many have shrunk from the moment. On May 4, the foundation gave the award to former Vice President Mike Pence, who withstood Trump’s extraordinary pressure to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

A business titan is not nature’s rebel. Rubenstein’s vote to honor Pence for standing up to Trump likely did not escape the president’s notice. So maybe that counts for courage. But couldn’t a man with all that money, and all that power, do something more for the country he loves? Rubenstein shook his head and gave me a look that suggested that, like most of his class, he’d already made up his mind.

The post The End of Soft Power in Washington appeared first on The Atlantic.