It was one of humanity’s greater vanities that we ever questioned whether there are any planets in the universe beyond the eight in our little solar system. Our sun is a perfectly ordinary star, residing in a perfectly ordinary galaxy, out in the suburban fringes of one of the Milky Way’s spiral arms. There are more than 100 billion other stars in the galaxy and, in turn, up to two trillion galaxies in the universe. The physics are the same everywhere, and if our solar system could spin up planets out of the leftover dust and gas that formed the sun, others should be able to do the same.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Still, science being science, we needed proof—and we got it in 1992, when two astronomers found two planets orbiting a pulsar 2,300 light years from Earth. Since then, over 6,000 confirmed exoplanets—or planets orbiting other stars—have been found, leading astronomers to conclude that there is at least one planet circling practically every star in the sky. The Kepler Space Telescope, which launched in 2009 and operated for nine years, is credited with discovering at least 2,300 of them. Other spacecraft, including the James Webb Space Telescope, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, and the Hubble Space Telescope have also been on the exoplanet trail, as have several ground-based telescopes.

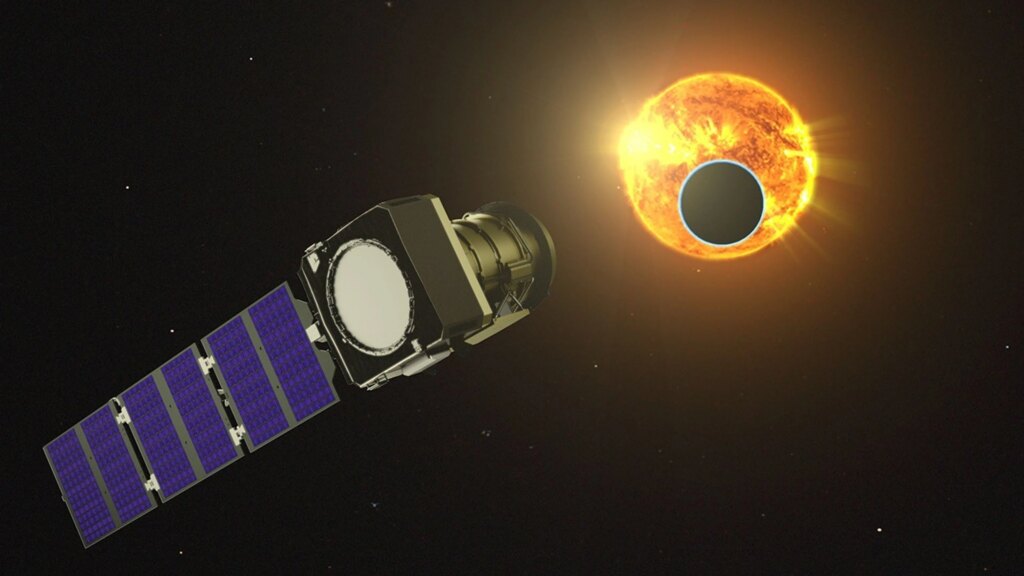

Now, a new space telescope is poised to fly sometime in the first quarter of 2026, looking nothing like the exoplanet observatories that went aloft before it and doing nothing like the job they’ve done. The latest planet hunter, dubbed Pandora, is a flyweight machine, tipping the scales at just 716 lbs. and measuring just 17 inches across, not counting its solar panel. That’s a rounding error compared to the Webb telescope, which is as large as a tennis court and weighs 13,000 lbs. Pandora will operate for only a year, and unlike Kepler and the others, which observe bushel baskets of planets, it will pay attention only to 20 hand-selected ones—but it will study them for vastly longer than any other telescope has, staring at a star system for up to 24 hours at a time and repeating each such session nine more times for every star it studies. Those detailed observations could go a long way toward determining if the conditions for life exist on distant worlds. But the job won’t be easy.

Exoplanets are far too small and dim compared with their parent star to be observed directly. Instead, space- and ground-based telescopes use one of two inferential methods. The first, known as the radial velocity technique, looks for slight wobbles in the star’s position, as the gravity of an orbiting exoplanet tugs it one way and then the other. The more marked the wobble, the more massive the planet.

The second, known as the transit method, looks for a slight dimming in the star’s light as the planet orbits in front of it. The change is fantastically small—the equivalent of removing a single light bulb from a board of 10,000 of them, according to Natalie Batalha, former Kepler mission director. The greater the dimming, the larger the diameter of the planet.

The transit method does more than simply confirm the existence of a planet. It can also tell astronomers something about its environment and chemistry. As background starlight streams around the planet, some of it passes through the atmosphere. That portion of the starlight is changed as a result, with its brightness and wavelength shifting, consistent with certain elements and compounds in the planetary air. If hydrogen is in the atmosphere, for example, the light will change in one way. If water or carbon dioxide or nitrogen or other components are present, it will change in others.

“Almost all of these planets have been studied, but they have been studied at varying degrees, and with [different levels of] success,” says Daniel Apai, professor of astronomy and optical sciences at the University of Arizona, and the scientist tasked with overseeing Pandora’s mission operations center housed at the school’s Space Institute. “The special power of Pandora will be these many revisits and extended monitoring of the star to build up a comprehensive picture.” Apai thinks Pandora compares favorably to the much larger and more powerful Webb, which has greater sensitivity in its observing instruments, but could never spend so much time focusing on individual stars because of the huge demand for observation time on the telescope from astronomers around the world.

The work Pandora does will be more challenging than just looking at the filtered starlight and copying down the chemistry it reveals. That’s because stars are not steady, unchanging sources of illumination. There are brighter, hotter regions on the surface called faculae, and cooler darker ones similar to sunspots. They change and grow and shrink and move as the star rotates, and can bollix up the readings the astronomers are trying to take.

This is most troubling in the case of water, which is essential for life as we know it. According to Ben Hord, a NASA postdoctoral program fellow at the Goddard Space Flight Center who spoke at the 245th meeting of the American Astronomical Society last January, variations in the light of the star can mimic or erase the signal of water. Teasing apart those false signals from the true ones across the chemical spectrum is the reason Pandora spends so much time, star by star, in its observation sessions.

“We observe how the stars rotate around, how different active regions appear and disappear in the visible hemisphere,” says Apai.

“We’re going to map out to see where the stellar contamination really starts to impact you,” says Elisa Quintana, Pandora’s principal investigator. “So we’ll be able to disentangle that.”

Choosing just which 20 planets to study out of a sky full of worlds was not easy. “We selected planets that orbit hotter stars and planets that orbit cooler stars,” says Apai. “We selected larger gas giant planets, and then also smaller sub-Neptune ones. We had about 100 interesting candidates at first and then made cuts.”

Adds Quintana: “We basically went through and divvied them out. We did all these literature searches on them to identify which ones would be good candidates.”

Among the features the Pandora team was looking for was water vapor in the star system, allowing the spacercraft to study that chemical signature more closely and see if a target planet itself was watery too. Hydrogen escaping the system, on the other hand, would suggest a planetary candidate that was being overheated by its sun. “In one system, hydrogen was spotted leaving the planet, which was attributed to the planet being pretty close to its host star,” says Apai.

The spacecraft will do all of this work for pennies on the dollar. The Webb telescope is the most expensive space observatory ever built, ultimately costing north of $10 billion. Pandora will fly for the relative pocket-change amount of $20 million.

Pandora’s big day—when it lifts off from a Kennedy Space Center pad aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and settles into low-Earth orbit—is coming soon, but NASA admits it can’t say exactly how soon. Scheduled for launch some time in the fourth quarter of 2025, the spacecraft remained grounded due to the 43-day government shutdown, waiting for Washington to reopen for business. For now the space agency is tentatively planning for a January launch.

Whenever the spacecraft does fly, the Pandora team is hoping that additional funding down the line might allow the mission to continue past the one year it’s budgeted for. “If things all go well, we plan to propose an extended mission to use the telescope for another year,” says Apai. Somewhere out there may lie a planet that could be home to life. Pandora just needs the time to find if it exists.

The post This Space Telescope’s Entire Job Is to Search For Signs of Life On 20 Distant Planets appeared first on TIME.