Photographs by Hannes Jung

The Bendlerblock is an imposing neoclassical building near the center of Berlin—severe and symmetrical, with a red-tile roof. It once served as the headquarters of the Wehrmacht, and it’s where officers who plotted to kill Hitler in 1944 were executed by firing squad. Now the complex houses Germany’s defense ministry, which oversees the armed forces.

I went to the Bendlerblock this past summer to meet with German military officials and see how they’re responding to an aggressive Russia and a mercurial America. Two sergeants escorted me to the office of Lieutenant General Christian Freuding.

At the time of our meeting, Freuding was in charge of the ministry’s Ukraine unit, but he had just been named the next chief of the army, a role he assumed in October. His actual, ambivalent-sounding title is inspector of the army. Freuding is gaunt and soft-spoken, with something of an aristocratic bearing. He doesn’t come from a long line of military officers, he told me, but his grandfather served in both world wars and was imprisoned by Allied forces in 1945.

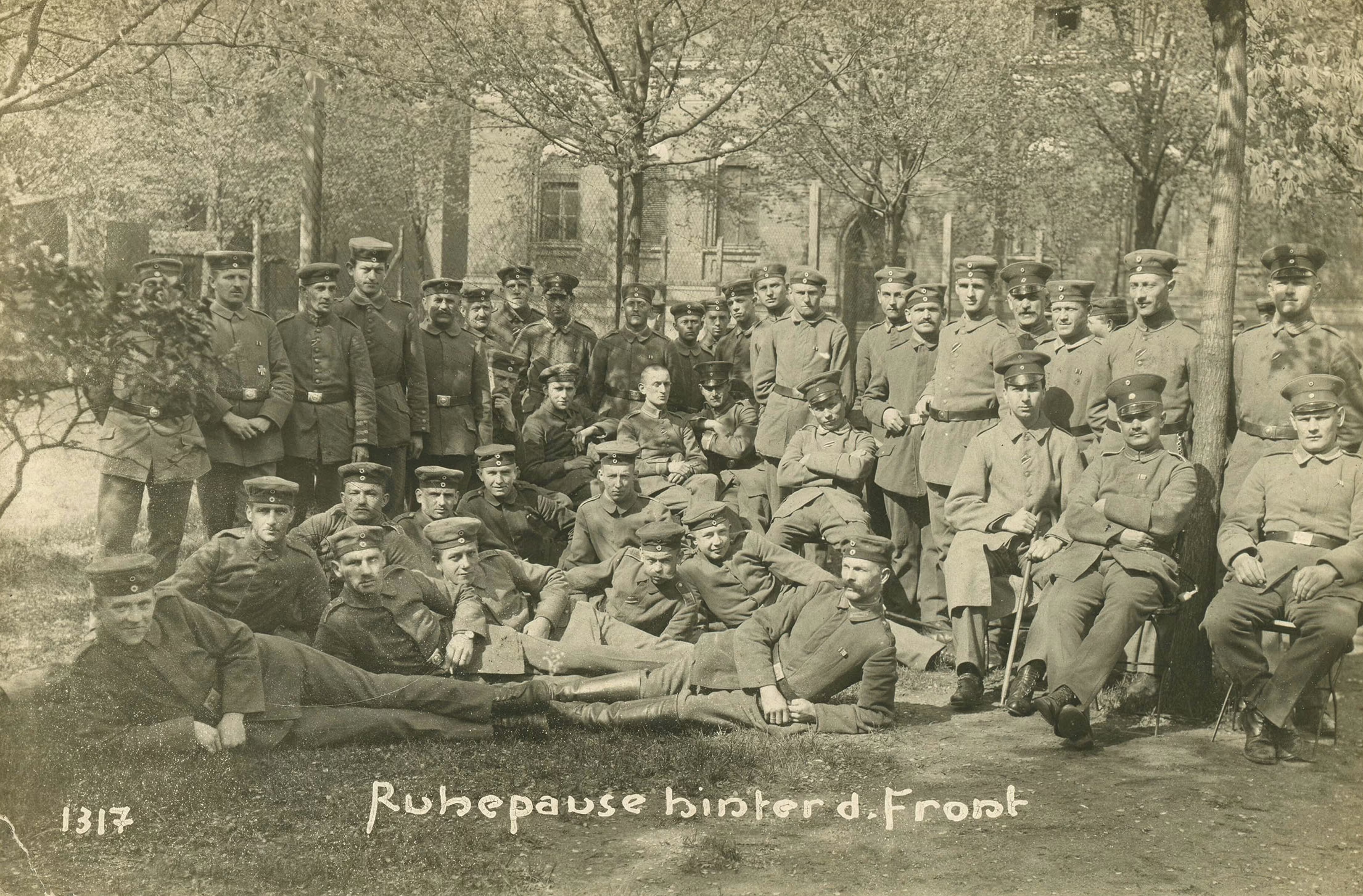

I told him about my own German family. A century ago, my great-grandfather Hans Salzmann was a soldier in the German army. He fought in the First World War and was wounded near Verdun and awarded the Iron Cross before returning home to practice medicine. But then his country turned on him. When the Nazis stripped him of his citizenship, he fled, sailing from Hamburg to Cuba and then to New York City, with a red J stamped on his passport.

Freuding nodded. “So you have a very personal relationship to this topic as well,” he said.

The topic in question was the past and future of German militarism and its meaning for German society—a topic about which my great-grandfather thought deeply. He clung to the belief that his homeland would one day be redeemed—that the nation of “Dichter und Denker,” of poets and thinkers, had not “disappeared entirely beneath the dirt and mud of the Third Reich.” He wrote these words soon after the Nazi surrender, as the Allies destroyed what was left of Germany’s war machine and put its leaders on trial for crimes against humanity.

At first, disarmament was imposed on Germany. American and Russian forces seized weapons depots, sealed off factories, and sent trainloads of military equipment out of the country. During the Cold War, countering the Soviet threat required a new West German military, rebuilt from the ranks of former Nazis, but always under Washington’s supervision.

[From the December 2022 issue: Clint Smith on how Germany remembers the Holocaust]

Germany eventually embraced its own relative powerlessness as a symbol of atonement, and of human progress. After the Cold War, the country’s pacifism became a mark of its faith in a global system of rules and treaties. Germany, the thinking went, could relinquish its own self-defense because brutish competition for continental dominance was over.

What made this possible was U.S. power, and in Germany, signs of it were everywhere—on bases where American troops were deployed and American nuclear weapons were stored, in cafés where Radio Free Europe broadcast American news and music, in schools and hospitals rebuilt under the Marshall Plan. Freuding said that he spent time as a teenager in the 1980s at American bars in Grafenwöhr, a town near a U.S. Army garrison that serves as one of NATO’s most important training bases. American soldiers were a constant presence, and he liked them. To Germans, Freuding said, the soldiers seemed steady, dependable—an embodiment of the American-led order.

But now that order is vanishing, Freuding said. My presence seemed to offer him something he’d been missing: an interested American audience for his worries about European security. Freuding had once been able to text American defense officials “day and night,” he said, but lately communication with his counterparts in Washington had been “cut off, really cut off.” The Trump administration had offered no warning, for instance, about its move to suspend certain weapons shipments to Ukraine. For information about American policy, Freuding has looked to the German embassy in Washington, where “there is somebody who tries to find somebody in the Pentagon.”

The faltering of American support couldn’t come at a worse time. The German officials I met, a sober group of military planners, spend their days watching Moscow’s troop mobilizations, trying to determine if Vladimir Putin will order an attack on a NATO country by the end of the decade and whether the American president would, in such a case, come to Europe’s defense. “You not only have an enemy knocking at the door,” Freuding said, “but you also are in the process of losing a true ally and friend.”

So Germany has recognized that it needs to rearm. It’s spending billions on weapons and repurposing civilian industries for arms production. It’s even debating whether to reintroduce conscription. The government has promised to transform the army into the strongest in Europe. For the first time since the Second World War, Germany is permanently stationing troops beyond its borders.

Not long ago, these plans would have set off international alarms. But as the United States upends the global order it created, Germany may have no other choice.

Boris Pistorius, the German defense minister, couldn’t believe what J. D. Vance was saying. On the main stage of the Munich Security Conference last February, the vice president was attacking America’s NATO partners, comparing European democracies to authoritarian regimes and accusing Europe’s leaders of stifling free speech and suppressing support for far-right parties. The targets of his criticism sat before him: the presidents of the European Commission and the European Council; heads of government from countries including Germany, Sweden, Ireland, and Latvia. A stunned silence fell over the grand hall of the Hotel Bayerischer Hof.

The annual security conference is traditionally a chummy event, sometimes described as a “transatlantic family meeting.” It’s not always harmonious; in 2003, Germany aired doubts about American plans for the war in Iraq. But criticism of the host country is considered uncouth. And in recent years, the meeting in Munich has represented a show of Western solidarity with Ukraine. But Vance used the conference as a platform for MAGA grievances. “The threat that I worry the most about vis-à-vis Europe is not Russia; it’s not China,” he said. “What I worry about is the threat from within.”

Pistorius couldn’t let the vice president’s comments pass without rebuke. “That is unacceptable,” he shouted in English from the second row. Vance continued, unfazed. Later, at the lectern, Pistorius declared that he must “explicitly contradict and oppose” Vance’s claims before turning to the focus of the conference: European and international security. Because the White House was pressing for a quick settlement to Russia’s war in Ukraine, and signaling that Europe would have to enforce the terms, Pistorius warned, “The choices we make now will determine whether we live in peace or in crisis.”

[From the October 2022 issue: Ukrainians are defending the values Americans claim to hold]

Pistorius has a restless air about him; his gait is hurried, his gestures emphatic. When I met with him at the Bendlerblock, he told me he’d never imagined that he would lead his country’s rearmament. His father was a pacifist who didn’t allow toy guns in the house. During the Cold War, Pistorius joined the Social Democratic Party, which had made Ostpolitik, aimed at easing relations with Moscow, the center of its foreign policy. “America is indispensable,” went the credo, but “Russia is immovable.” But after the Iron Curtain fell, Pistorius recalled, Germans thought they were living in a world without threats.

After Russia’s annexation of Crimea, in 2014, Germany agreed to work toward spending 2 percent of its economic output on defense within a decade. But its progress was slow in the years that followed, and Donald Trump complained in his first term that Germany and other NATO members weren’t paying their share. German soldiers told me it was common then for members of the officer corps to purchase their own gear: boots, pants, field jackets.

Then, in 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. At the outset of the war, Europe’s largest since World War II, Germany’s army chief admitted in a public post that the forces under his command were “more or less bare.” The German government declared a Zeitenwende, or “turning of the times.” It promised a burst of cash for the Bundeswehr—the armed forces—that would finally bring the country, which has Europe’s biggest economy, in line with NATO targets. A second shock came not long after the Munich Security Conference, when German officials watched in disbelief as Trump, in a televised Oval Office meeting, reprimanded Volodymyr Zelensky for refusing peace on terms dictated by the White House. Freuding said that he had never sent as many texts in a single night as he did on that occasion, to his friends and colleagues in Ukraine.

[Read: The beginning of the end of NATO]

For Friedrich Merz, then the chancellor-in-waiting, the confrontation made clear that Europe could no longer rely on the United States. A senior German official who spoke on the condition of anonymity told me that Merz, a member of the center-right Christian Democratic Union, is haunted by the question “Will America serve its allies to the dogs?” After the spectacle in the Oval Office, he became convinced of the need to amend Germany’s constitution to authorize unlimited government borrowing for defense. Within a month, the Bundestag approved the reform.

Görlitz is Germany’s easternmost city, adjacent to the Polish border. It was spared Allied bombing during World War II, and its old town bears the imprint of centuries of European history. Now Görlitz offers a glimpse of the future: At a ceremony there last February, then-Chancellor Olaf Scholz heralded the city as a hub of rearmament. Production lines once used for double-decker train cars are being altered to make parts for Leopard 2 battle tanks, Puma infantry fighting vehicles, and Boxer armored vehicles. The defense firm KNDS is taking over a factory from the rail company Alstom. The transition will be complete in 2027.

I asked Pistorius why manufacturers can’t move faster, noting that Germany has been adept at making tanks when it puts its mind to it. He said the companies, like the rest of German society, had grown accustomed to peacetime. When the Cold War ended, and a reunified Germany reduced its military, tanks were sold abroad or scrapped for metal and parts. By one estimate, Germany had only about 340 tanks by 2021.

According to Bruegel, a Brussels-based think tank, effective European deterrence—averting a Russian invasion of the Baltics, for example—would require 1,400 tanks and 2,000 infantry fighting vehicles, more than the combined capabilities of Germany, France, Britain, and Italy. Although all four countries are spending more on their armed forces to close the gap, no other Western European country matches Germany, which will devote more than 460 billion euros, or $538 billion, to the Bundeswehr over the next four years.

But in Görlitz, the shift to weapons manufacturing has run up against the growing power of political extremes. The far-right Alternative for Germany is the largest opposition bloc in the Bundestag, controlling nearly a quarter of the seats. The party’s base of support is in the former Communist East, where economic hardship fuels nostalgia for the world before German reunification, and sympathy for Moscow endures. The AfD’s national co-leader Tino Chrupalla, who represents Görlitz in the Bundestag, is scornful of the need to deter Russia. In 2023, he wore a tie with the Russian tricolor to an event at the Russian embassy in Berlin. And in a recent interview with a German broadcaster, he asked, “Do we really believe that we can defeat the world’s greatest nuclear power and win this war that isn’t even ours?” Sebastian Wippel, the AfD candidate who narrowly lost Görlitz’s mayoral race in 2019, told me that weapons made in the city must be used only to defend Germany, not to arm Ukraine. Deterrence, he said, can’t mean “threatening Russia.”

Some on the left are also skeptical of rearmament. Environmental and social activists protested in the spring against the planned assembly of weapons in Görlitz. NEVER AGAIN WAR! reads graffiti on a factory wall. Outside the plant that will soon manufacture tanks, I met an expert in the technical preparation of train parts who has worked in the rail industry for 16 years. He told me he would transfer to a factory in a nearby city to avoid making weaponry. “I want no part in it,” he said.

Across the Spree River from the Bundestag is an office building occupied by a start-up that makes suicide drones. On the ground floor is a showroom with an elegant minimalist aesthetic, a space so airy and bright that it could be an art gallery—except that military payloads fill the glass display cases. In one corner stands a drone. It’s tall, like a Giacometti sculpture.

The drone is named Virtus. It takes off vertically and tilts in the air to fly like a plane, a loitering munition with four rectangular wings. Guided by artificial intelligence, it circles a target area, identifies an enemy asset, and slams into it with an explosive warhead. The start-up, called Stark, has begun supplying the German armed forces with weapons for testing and certification, and the government plans to purchase a large stock of such drones next year.

Stark was founded in Berlin in 2024, and now has outposts in both England and Ukraine. It works only with NATO and allied militaries. The company’s drones are easy to assemble, a Stark spokesperson told me. This is important because armies differ in their techniques; the Ukrainians, for instance, use Velcro to strap the warhead in place.

The company’s pitch is that a drone is cheaper, and more cost-effective, than a tank. Powered by a battery, Virtus can fly for about 60 minutes at a cruising speed of 75 miles an hour, and dive at up to twice that velocity. The aim was “to make this kind of equipment a commodity, to make it easy to order it, easy to produce it, and easy to pay for it,” Johannes Arlt, a former air-force officer and Social Democratic Party politician who is now a Stark executive, told me. On his phone, he showed me a video of the drone landing deftly on a piece of printer paper.

Germany has long been inhospitable to defense start-ups because of too little demand and too much political opposition. But the country’s venture-capital firms have lately been flooded with proposals from such start-ups, according to Jack Wang, who leads investments in defense technology at a firm called Project A. The proposals cite Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference and Trump’s Oval Office confrontation with Zelensky, appealing to investors who see opportunities in the White House’s animus toward Europe. One is Peter Thiel, a Vance mentor who has invested in Stark. Another is the American venture-capital firm Sequoia Capital, whose most outspoken partner, Shaun Maguire, is a prominent Trump supporter.

As the Germans ramp up their own arms production, they still need to import weapons from abroad. I met with Colonel Dennis Krüger at the General Steinhoff Barracks. The facility was built by the Third Reich on the outskirts of Berlin, and later became a site of the Berlin Airlift, receiving the supplies that sustained the city during the Soviet blockade. Now the barracks are home to Germany’s air force. In the courtyard, Krüger showed me a retired Patriot launcher. Made in the United States, the anti-ballistic-missile system is a pillar of NATO air defense, able to neutralize drones, cruise missiles, and tactical ballistic missiles.

Recently, though, Germany has begun to look beyond the U.S. for air-defense weaponry. Krüger told me about traveling to Tel Aviv to fine-tune a missile-defense system purchased from the Israelis that can intercept and destroy long-range ballistic missiles in space. On the sleeve of his military shirt, below a decal of the German flag, is another with Hebrew lettering, the logo of the weapons project: Arrow 3. For decades, Germany has been a top exporter of arms to Israel, its commitment to the security of the Jewish state a legacy of the Holocaust. Arrow 3, the largest defense deal in Israeli history,reverses that logic by making Israel a guarantor of German safety.

Krüger said that work on the weapons system turned representatives from the two militaries into a “family,” and that they built camaraderie when his staff waited out missile attacks in Tel Aviv’s belowground shelters with their Israeli counterparts. The weapons acquisition from Israel is “one next step,” Krüger said, “in overcoming our history.”

Weapons—even unmanned drones—need soldiers to operate them. On the sidewalk outside a Berlin military-recruitment office, I met a young German named Julian Boy. At the time, the Bundeswehr was advertising an open house on its website: “Do you know exactly what you want? Then join the Bundeswehr now.” Boy, who is 24, fit and broad-shouldered with close-cropped hair, looked like an ideal recruit. Boy did know exactly what he wanted, and it was not to join the military.

He told me that he believes Germany should have more weapons and troops. “I don’t know if America will be there to support Europe,” he said. “So we need to do it ourselves.” But he has never considered enlisting. He already has a job, as a metalworker. Besides, the Bundeswehr’s deficiencies were legendary. Stories of scarcity and incompetence—that’s what his generation knows of the army. “It’s a meme,” he said. “Munitions being used up in two minutes.”

Changing this perception is the defense ministry’s hardest task. NATO targets call for a German fighting force of 260,000, far more than the country’s current roster of about 182,000 active-duty soldiers. Thomas Röwekamp, who chairs the Bundestag’s defense committee, told me that the government needs to convince a generation raised in peacetime that they can’t take their safety for granted anymore.

Germany is set to begin compulsory military screening in 2026, but won’t yet resume conscription, which was suspended more than a decade ago. All 18-year-olds will receive a questionnaire assessing their willingness to join the armed forces; men must respond, and women will have the option to do so. The hesitation about a draft—which Röwekamp argued will eventually be necessary—struck me as evidence of Germany’s abiding unease about preparing for war. Pistorius still hopes that a voluntary model can work.

Recruitment advertising is everywhere. A TikTok series offers a “road trip”through the Bundeswehr—the chance to follow four influencers on military missions. Calls to enlist adorn train stations and buses, even fast-food packaging. DO YOU HAVE WHAT IT TAKES? asks text printed on pizza boxes.

In the decades since World War II, Germans have developed a deep aversion to anything that resembles the Nazi veneration of the soldier. They’ve been outraged by recent scandals that seem to reflect the Third Reich’s lasting imprint on some corners of the military. In the special forces, a sergeant major placed under investigation in 2017 was alleged to have stockpiled stolen ammunition and explosives alongside Nazi memorabilia; at a party, soldiers were said to have performed the Nazi salute, which is banned in Germany. One special-forces unit was so rife with right-wing fanaticism that the defense ministry disbanded it in 2020. Today, screening for extremism is a Bundeswehr priority.

The last time Germany had a permanent armed presence in Lithuania was during the Nazi occupation, when the Wehrmacht swept east, invading the Soviet Union. By the end of the war, the Jewish population of Lithuania had been slaughtered. Near Vilnius, the capital, killing squads dumped corpses into trenches dug in the forest.

Now Germans carrying guns are back in Lithuania. They’re stationed in Vilnius, in an office building in the city’s business district, where the seventh floor is reserved for Panzerbrigade 45, the first permanent foreign deployment of German troops since the Second World War. When I visited the brigade, groups of soldiers were hanging out on the sidewalk, smoking cigarettes.

The German soldiers’ mission is to help fend off a Russian attack. Vilnius is their temporary home; a permanent base for the brigade, projected to number about 5,000 by 2027, will lie near the border with Belarus, the Russian client state that serves as a depot for dozens of Moscow’s nuclear weapons. Lithuania, a NATO member since 2004, is particularly vulnerable because it’s located along the Suwałki Gap, the 60-mile expanse separating the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad from Belarus. That strip of land is NATO’s only overland route connecting Western Europe to the Baltic states, and the alliance’s leaders worry that Putin could try to seal it off.

Brigadier General Christoph Huber, who leads the German soldiers in Lithuania, showed me a 3-D model of the barracks, which will include training fields, sports grounds, and housing. “We are here to defend every inch of NATO territory,” he told me. “To put on the fight against”—he paused, correcting himself—“the possible fight against Russia.”

The strategic logic is clear. Still, I wondered how Lithuanians felt about the sight of German soldiers. Across the street from the brigade’s headquarters is the old Jewish cemetery of Vilnius, a city once called the Jerusalem of the North. PLEASE RESPECT THIS PLACE FOR THE ETERNAL REST OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE states a plaque bearing a Star of David. It stands as a reminder of the Nazi past. But for the people I met in the residential neighborhoods of Vilnius, memories of Soviet terror are fresher, and fears of Russian aggression are ever present. A young mother told me that her family had suffered under Soviet collectivization policies, and that she feels safer with German soldiers around. I approached another resident, a scriptwriter who said only, “We live next to a shit country.”

I got the sense that the German military is more popular in Vilnius than in Görlitz. Huber told stories of being stopped on the street and thanked for defending Lithuania. We sat in his office, where German, Lithuanian, and NATO flags hung. He described ceremonies held in the spring to inaugurate the brigade, festivities that brought the chancellor and defense minister from Germany. In Vilnius cafés, Lithuanians insisted on buying coffee for his troops. The display panel on the front of city buses announced LTU DEU. Lithuania loves Germany.

DEU. Lithuania loves Germany.

The defense ministry points to the welcoming of German troops as proof of Europe’s support for its military buildup. “The fear of a weak and indecisive Germany is bigger than the fear of a strong Germany,” Pistorius said.

Huber said that his troops are receiving Germany’s most advanced military equipment, including the newest Leopard tanks. They are training on territory where they might go to war, crossing anti-tank ditches, dodging mine obstacles, and navigating rivers. Huber is studying Russia’s tactics in Ukraine, anticipating the “war of the future.” His battalions will become experts in electronic and drone warfare. “The Panzerbrigade 45 has the top priority within the German army,” he said.

The general has a paperweight on his desk quoting Winston Churchill: ACTION THIS DAY. I asked him about another Churchill maxim, delivered in an address to the U.S. Congress in 1943. The Germans, according to the British prime minister, are “always either at your throat or your feet.”

“Much has changed,” Huber said without emotion. There is nothing distinctive, he added, about the German capacity for evil. “We have to be aware of human beings, in general, having a dark side.”

In June, as part of a “Day of Values” observed within the German army, members of the Panzerbrigade cleaned up graves at a Jewish cemetery in Merkinė, a Lithuanian town where hundreds of Jews were shot by Nazi forces and local collaborators in 1941. Some of the tombstones are more than a century old. The soldiers wiped away the dirt that had collected from decades of neglect. The Jews who might have tended the graves of their ancestors are dead, Huber said. “Germans killed them.”

A bronze statue of a naked man with bound wrists stands in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock. It honors the army officers who tried to assassinate Hitler, and who were shot in the courtyard on a summer day in 1944. Toward the end of my interview with Pistorius, after we had discussed tanks and soldiers, I asked him if he finds the statue at all incongruous.

Germany must be the only country in the world, I said, to place a memorial to an attempted coup within its defense ministry. Pistorius said that he appreciates the statue as a reminder of the democratic sources of his country’s military power. “No oath is ever taken again on a leader, but on a constitution.”

But constitutions can be amended. And the oaths of soldiers can change as well, depending on shifting political tides. If the AfD continues its march to power, an illiberal German government could reverse the country’s international allegiances—the tanks and drones now equipping the Ukrainian resistance instead advancing Russian interests, the army-building set in motion for the defense of liberal democracy exploited by a resurgent German militarism. Listening to plans for rearmament in the old Wehrmacht headquarters, I wondered whether Germany could get power right this time.

Of course, militarism can serve illiberal ends anywhere, if democracy becomes fragile. The Trump administration has shown an early willingness to deploy the National Guard, and even regular Army units, to American cities. “I could send the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines—I could send anybody I wanted,” Trump has said. Such rhetoric shocks Germans because it’s reminiscent of their own country’s past.

After the war, my great-grandfather remembered acts of resistance. He knew a professor in Berlin who read poetry to the Brownshirts in his class, explaining, “That’s from the Jew Heinrich Heine”; a taxi driver who took a hunted Polish Jew to the Czechoslovakian border to escape; a father who brought his young daughter to see a burning synagogue, telling her, “Never forget those misdeeds of the Nazis.”

Where were “the ‘good’ Germans?” my great-grandfather asked. In jails and concentration camps, he answered, and buried in the earth. But as a refugee, “rescued here on the foot of the Statue of Liberty,” he believed American influence would help secure peace and purge Europe of fascism.

For a time, it did. But that world is disappearing, and Germany’s pacifism belongs to another age.

This article appears in the January 2026 print edition with the headline “The New German War Machine.”

The post The New German War Machine appeared first on The Atlantic.