In December 2020, a reader suggested I get in touch with a young Pasadena man named Edgar McGregor, who was approaching 500 straight days of picking up trash in local parks, including Eaton Canyon. I connected with McGregor by email but then got sidetracked by other things, as did he.

McGregor, now 25, still is picking up trash, and he also picked up a climate science degree at San José State in 2023. He operates a weather forecasting service out of his home, with a focus on the foothill communities of the San Gabriel Mountains, and has a keen interest in Santa Ana winds. This brought him a sizable following of people who paid close attention to his forecasts, particularly in January.

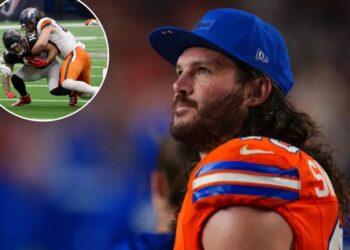

In his home office, McGregor studied computerized weather data and saw the makings of a monster. He knew the Santa Ana windstorm bearing down on the Altadena area would be catastrophic, and after a fire sparked in Eaton Canyon, possibly from arcing utility lines, he posted a video imploring his followers to “get out.” His warning, which sent caravans of vehicles down from the foothills, has been credited with saving lives.

A few weeks ago I finally went out with McGregor on a trash pickup. We met at the Santa Fe Dam Recreation Area, where he pulled plastic bags, bottles, cans, food wrappers and other rubbish out of thick, dry brush. He said the Irwindale location would offer us a sweeping view of the San Gabriel Mountains, which dramatically form the back wall of L.A. sprawl and serve as a reminder that along this towering creation of seismic sculpture, natural beauty and risk are inseparable.

Part of that risk, McGregor explained, is that when high-pressure air to the north and northeast is drawn toward low-pressure air along the coast, it gets compressed as it’s funneled and slung through canyons, it accelerates as it descends Southern California mountain ranges, and it becomes dangerously dry, threatening everything in its path.

“So, I credit my ability to forecast Jan. 7 … with my trash pickups,” McGregor told me, explaining that he had taken full notice of the distressed ecosystem at Eaton Canyon after two straight years of drought, which produced a heavy load of kindling.

“I knew it would be catastrophic. … Even before I ran outside to look at the hillside behind my house ablaze, I knew it was over. It was totally over. The whole canyon was going to go up,” McGregor said. “Spending so much time in that park and learning its natural history, when debris flows happened, when wildfires happened, what caused wildfires to destroy homes in 1993, I knew … this was the start of a new era for Altadena, right then and there.”

From my front porch on a clear morning, the San Gabriels sometimes do not look real. It’s as if a Hollywood crew worked through the night to assemble a movie set backdrop, with impossibly steep rock walls towering over the valley. In a matter of minutes, I can disappear into the mirage, trading traffic for tranquility.

But gravity has not been kind to the San Gabriel range and its foothills, where majesty and mayhem have lived together through decades of deadly fires and floods. In 1934 the new year began with a 20-foot wall of mud and debris thundering down from fire-scarred slopes and devouring much of La Crescenta and Montrose, gutting 400 homes and killing 45 people. In 1968 and 1969 the same one-two punch of fire and floods hit Glendora, wiping out 200 homes and killing 34.

The perennial threat along these sharp slopes was meticulously explored in a 1988 New Yorker article by John McPhee. He revisited the deadly 1978 La Crescenta mudslide, which picked up more than a dozen vehicles and parked them downstream while also destroying homes.

“Los Angeles Against the Mountains,” as the story was titled, had a clever opening sentence: “In Los Angeles versus the San Gabriel Mountains, it is not always clear which side is losing.” The piece began with the travails of Robert and Jackie Genofile and their two teenagers, Kim and Scott, who were nearly buried alive in their La Crescenta home.

Kim Genofile was 17 at the time of the storm. I wasn’t sure I had the right person when I dug up a phone number for a woman living in Orange County, but Kim Flotron answered and said she was indeed the former Kim Genofile, and she’d been thinking about the unfortunate souls by the thousands who lost everything in the Eaton fire.

Flotron, retired from a career in medicine, spoke as if the 1978 ordeal was still fresh in her mind. She said she couldn’t sleep the night of the disaster and went into her brother Scott’s bedroom and looked through the window at the storm. Flotron remembers telling their mother, “You should see all the rain that’s coming down.”

A series of debris basins protects neighborhoods in the San Gabriel foothills, catching storm runoff that can include mud, trees, rocks and boulders. The one above the Genofile house got clogged in the storm, and an avalanche of debris barreled down the hill.

“I can still hear it, to this day,” Flotron said.

Mud crashed into and plowed through the house, climbing the walls. Flotron said her father told everyone to jump onto the bed in the master bedroom, and she and her brother tried.

“But our legs got trapped by a boulder, and we were stuck,” Flotron said.

The Genofiles dug their way to safety, and the teens suffered only minor cuts and scrapes. Flotron told me her father, a contractor, had built the house that was destroyed and the family members decided to rebuild in the same location, despite the nightmare they’d survived.

There’s Los Angeles versus the mountains, as McPhee put it, but there’s also Mother Nature versus human nature, and home is home. As one Altadena fire survivor put it when I asked if he felt safe rebuilding in a place with such a storied history of shaking, baking and assorted other risks, he shrugged me off. Risk is everywhere, he said. And true enough, if one thing doesn’t get you, it’ll be another. Crime, accident, disease.

Flotron said that in their new house, the bedrooms were placed upstairs, to make for sounder sleep.

“We’re just very strong-willed people and have a tendency to be more positive,” Kim said of the decision to stay in La Crescenta. “My parents had this thing that, we have our lives, we’re not broken up. We thought we lost two cats, but we found one on a surfboard in the reservoir and one in a cabinet.”

She does think, though, that there has been lingering post-traumatic stress disorder in her family, and that her late father was never quite the same after losing the house and later shutting his business. Then, in 2009, the Station fire roared through the neighborhood, though the Genofiles were spared.

“That was frightening because it was like, what are we anticipating?” Flotron said. “It was all right there. You could watch the sumac explode and you could feel the heat.”

Her brother still lives in La Crescenta, Flotron told me.

“Whenever it rains,” she said, “we seem to talk.”

Seismologist Lucy Jones and I were walking down to the Gabrielino trail from La Cañada one day, talking about the assorted threats that hang over us in Southern California, testing both our preparedness and our sanity. She used to live in the general vicinity of the Genofiles and was evacuated from her home there for three days during the Station fire, only to hope and pray the following year that a debris basin near her home, filled nearly to the brim during a storm, would hold out. It did.

Before that, Jones had lived in the neighborhood where I live and said she was Richtered out of bed there in 1988 by the rude jolt of a 5.0 quake. After her adventures in La Cañada Flintridge, she and her husband, also a seismologist, wanted to be closer to their jobs at Caltech, so they began real estate shopping. Jones, working with the ultimate insider’s advantage, said they gave one home a pass after observing that it sat on the Raymond fault scarp.

“I might have been willing to gamble, but that wasn’t going to happen,” Jones said. “We’d never be able to invite a geologist to dinner.”

As we descended a winding path toward the trail, Jones spotted something that interested her on the face of a steep wall of rock.

“That looks like fault gouge,” Jones said, examining some bleached, sandy material sandwiched by darker, more solid rock.

She didn’t seem particularly alarmed, even though we were looking at what might be an example of what Jones called ridgetop shattering, which can be associated with seismic activity. And we were in the vicinity of the Sierra Madre fault, which conspired in prehistoric time with the San Andreas fault to form the San Gabriel Mountains.

Several million years ago, Jones said, there were no San Gabriel Mountains. The land was flat until a transverse kink in the San Andreas fault, which separates two great tectonic saucers — one sliding slowly to the southeast and one to the northwest — collected pressure that began pushing upward and forming the mountains. The San Gabriels still are climbing, and among the fastest-rising mountains in the world.

I often feel, when talking to Jones, that I’m asking questions that might get me kicked out of class. But I tried another one on her:

Why is this mountain range so steep?

“Because earthquakes are pushing it up faster than erosion is bringing it down,” Jones said, reminding me that the San Andreas is on the north side of the range and the Sierra Madre on the south side. “Every 5,000 years or so, the Sierra Madre fault moves again and pushes us up another 10 feet.”

As horrific as the Big One is sure to be, it’s easy enough to push that out of our minds because the timeline is unknowable. The next destructive quake could be in 5,000 years, or 10,000, or it might visit us before you finish the next sentence. Nobody knows. And there is no earthquake season.

But there are fire seasons, and in the evolving order of things that can go wrong, especially after what happened in January, L.A.’s proximity to wildlands seems ever more unsettling.

“Look at that hillside directly in front of us,” Jones said, gazing across the canyon. “That burned in the Station fire. That’s 16 years of regrowth, and it’s still struggling.”

In typical cycles, burned wildlands can take decades to recover. But they are struggling even in places not visited by fire, thanks to drought and other factors that have led to forest collapse.

We’re experiencing “a higher fire risk because of climate change,” Jones said. “The ecosystem is so stressed, because it’s experiencing a different climate than it evolved to experience.”

We reached the creek at the bottom of the trail and began winding toward the back side of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory on the edge of the Eaton fire’s western boundary. Along the way Jones pointed out the dynamics of change. In the sand along the creek and in boulders the size of dump trucks, she saw the map of historic reconfiguration.

“Look at the size of the rocks, and they’re rounded enough that they’ve been bouncing around in the stream for a while,” she said. “When fire happens and we have stuff coming down, the green burns and the soil comes sloughing off in the rain.”

At one point Jones reached across the gurgling creek to hand me her trekking poles for balance, so I wouldn’t take a spill on slippery rocks. As we approached the end of our hike she took me to a spot where, a few months ago, she identified a segment of the Sierra Madre fault.

“Sometimes you can see it really clearly,” Jones said, but rain had rearranged things, washing leaves and other materials down over the rocky ground.

She glanced across the creek, working with the aid of a geologist’s magic eyes, and spotted signs of another strand of the fault. She bent down to inspect some sandy material and said, “Look at how it’s all ground up in here against this very hard rock.”

If there were a big quake, Jones said, “we would expect these rocks will move about five meters up this way, and that’s going to be running into the bridge.” But in that scenario, the bridge, which crosses the creek at the back entrance to JPL, might already have been damaged from violent shaking.

Jones told me — awfully casually, it seemed — that big earthquakes always cause fires, that wood-frame construction can compound losses, and that the extent of the disaster “depends on what winds are blowing when the earthquake happens.”

I told her I needed to know that she sleeps OK.

“Yeah,” Jones said. “It’s geologic time.”

Jones, who spoke fondly of “playing in the mountains” with her grandchildren, left me with a few words of reassurance.

“I’m not moving,” Jones said. “And I’m not convincing my son to raise the grandchildren somewhere else.”

The Eaton and Palisades fires would not have been nearly as devastating without the Santa Ana winds that powered them, carrying embers great distances. Although there is no evidence at the moment that climate change has an impact on Santa Ana winds, which race over and along parts of the San Gabriel foothill corridor in the fall and early winter, there is evidence that climate change means elevated fire risk.

“The frequency at which we’re seeing autumns that are extremely dry is increasing,” Edgar McGregor told me. That means that when we enter Santa Ana season without having had much rainfall to douse vegetation, we’re primed for disaster.”

Another critical factor in the Eaton and Palisades fires was that the winters of 2023 and 2024 were unusually wet, producing vegetation that later became fuel in an unusually dry season. Daniel Swain and other climate scientists refer to these swings from drought to deluge as hydroclimate whiplash.

“When it rains, increasingly, it pours. That’s the way this is playing out globally,” said Swain, a researcher for the California Institute for Water Resources.

And why is that happening?

Because we’re playing with matches, burning fossil fuels, sending up more greenhouse gases and cooking the planet.

“I’m not sure that some folks are aware of how dramatically warmer it has become in the last 30 years,” Swain said. “Unfortunately, we’re on a trajectory for a lot more warming than we’ve seen so far,” and future warming will be exponential rather than linear.

“It’s obviously warmer, but why does that matter so much? Because of the atmospheric sponge effect,” Swain said. “As the temperature of the air rises, the size of the figurative atmosphere expands, and its capacity to absorb water does as well.”

The sponge is capable of both absorbing and dumping increasing amounts of water. A study published by Swain and other scientists reported that between 1980 and 2018 in California, human-caused climate change contributed to a doubling of the number of “autumn days with extreme fire weather.”

Swain said there’s some evidence of a shift in Santa Ana wind timing, with fewer winds in the fall and more in the winter. That’s potentially a good thing, because the later they are, the greater the chance that rains have arrived.

Jon Keeley, a research ecologist, UCLA adjunct professor and former Altadena resident, doesn’t buy the idea of a whiplash effect as an explanation for the January wildfires. He told me climate change is a bigger factor in the fires that hit Northern California’s heavily wooded areas than in Southern California’s chaparral terrains.

In January, he said, the primary factors were that Santa Ana winds blew at about twice their usual speed, and the fires were triggered. The Palisades fire was a reignition of an earlier blaze allegedly set by an arsonist, and the Eaton fire might have been ignited by sparking power lines.

Keeley said that once the fires got going, houses, rather than dry vegetation, were the fuel. More people means more power lines, more triggers and more development, and lowering the risk of fire requires a greater focus on all of those things.

“You cannot look at just climate change without … talking about population growth, and nobody is talking about population growth,” Keeley said.

Swain is in full agreement that climate change is only part of the story, and that there are lessons to be learned from January’s twin catastrophes.

“We could see much better fire outcomes in a higher fire-risk world if we do the right things,” he said, in terms of preparation and prevention, and how and where we build.

Swain mentioned Jones’ decades of work to educate the public on earthquake risk and preparedness, along with her campaign to elevate building codes and retrofit vulnerable structures.

“I’m almost in awe of the seismology folks who managed to convince people to prepare for something we’ve never seen before,” Swain said. “I want to get there with wildfire hazards.”

Many years ago I was out with a friend, kayaking over swells just beyond the jetty at the entrance to Marina del Rey. It was a warm, clear winter day, and as we headed back to shore, the snow-covered peaks of the San Gabriel Mountains spread out before us in the distance. In less than two hours you could go from swimming to skiing, or from having a dolphin slide under your kayak to having a bear dig through your trash can.

It’s easy enough to take this natural environment for granted, as many of us do. One of the things I admire about McGregor is that he doesn’t.

I told McGregor I’d spoken to two PhDs about the fires and that one emphasized the need to better understand the urgency of climate change, while the other was focused on reducing fire risk.

“We need to do both,” McGregor said. “I understand the importance of brush clearance, controlled burns and safer homes if you’re going to build” in the wildland-urban interface.

But over the last 119 years, by his computations, average daily temperatures in Pasadena increased by an alarming seven degrees.

McGregor — who lives at Pasadena’s northeast boundary, a block from Altadena — began working for L.A. County as a meteorologist after the fire but emphasized that he was speaking as a private citizen. One who was alarmed last January when, in his home office, he saw that the coming Santa Ana winds would be of high velocity and long duration.

Usually you get a high-velocity wind of short duration, he told me, or a low-velocity event of long duration. Santa Anas come in two flavors, he added, hot and cold, depending on their origin and characteristics.

“When we get the cold flavor, that’s when the winds dive over the mountains. They crash into the foothills below and they spread out. That’s what was carrying the Eaton fire into Altadena,” McGregor said.

I asked if his family considered moving, even though the house was not damaged. He paused before saying his grandparents built the house.

“It’s always been in the McGregor family, and it’s not really an asset to me, it’s a home. And you don’t consider those things with your home,” he said.

“So your home is safe,” I said, “but your house might not be.”

He said he hadn’t thought of it that way.

At the Santa Fe Dam, McGregor filled buckets with trash, saving his harshest comments for decomposing plastic bags. He distinguished native plants from non-native and said we need to better understand that in advancing wildfires, some trees — oaks, for instance — can be beneficial rather than hazardous.

“It’s not just that they have moisture in them and can eat embers for breakfast,” he said. “But also that they slow down the Santa Ana windstorms.”

McGregor said he changed his bio from climate activist to community activist because “that’s all-encompassing. I forecast weather when that’s what my community needs. I pick up trash when that’s what my community needs.”

He could let himself get overwhelmed by the declining health of the planet, or the dunderheaded indifference at the highest levels. But he chooses not to.

“I protect myself with the knowledge that I’m just an individual, and one that doesn’t have that much power, and I don’t let it get to me,” he said. “If I came out here every day and I just got angry with the litterbugs … I can’t think those thoughts, because I’m out here to enjoy the natural world and bring myself peace of mind.

“I get out of the house, go somewhere, take responsibility for a local natural area, be an example that others can live by. Maybe that meets the needs of the element within me that wants to have a purpose in this world.”

The January fires, which raged at the intersection of the built and the natural environments, were not the first in L.A. and won’t be the last.

They were humbling reminders that we’re temporary inhabitants of a place both blessed and cursed, tucked between ancient peaks and rising sea, with no greater calling than to be better stewards of our inheritance.

The post Amid catastrophic loss, the unshakable allure of the San Gabriel Mountains appeared first on Los Angeles Times.