TORONTO — Janice Willier was perusing the website of the Edmonton Opera one day this year when she saw plans for a production based on Indigenous writer Thomas King’s 2020 novel “Indians on Vacation.”

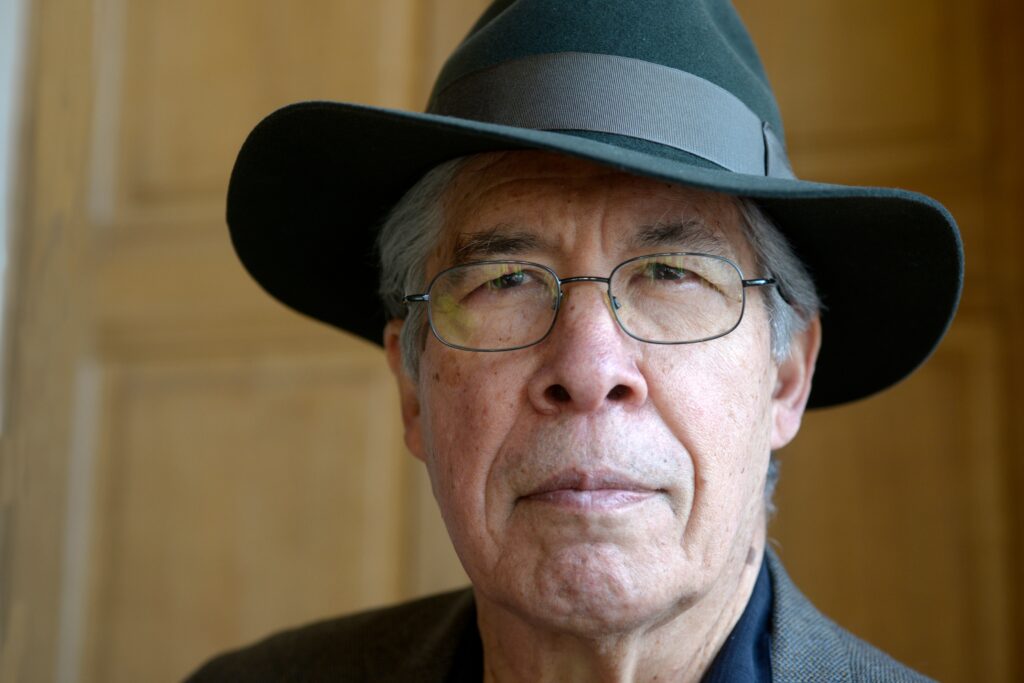

King has long used humor to pick apart stereotypes and illuminate the mistreatment of Indigenous people in North America. His 2014 nonfiction book “The Inconvenient Indian” has become a cornerstone of Indigenous literature and history course syllabi. The judges of one of several literary prizes it won here praised the work as “subversive, entertaining, well-researched, hilarious, enraging, and … hopeful.” A documentary adaptation premiered at the 2020 Toronto International Film Festival, where it was named Best Canadian Feature Film — the first of several honors it would win.

But Willier, a health project manager from the Sucker Creek First Nation, had heard rumors that King wasn’t, in fact, Indigenous. So she contacted the opera company — and within weeks, one of Canada’s most prominent Indigenous writers penned a new work: An essay in which he said he had learned he was not part Cherokee, as he said he was raised to believe. During a meeting with the Tribal Alliance Against Frauds, a U.S.-based nonprofit that aims to expose false claims of Indigenous identity, a genealogist presented him with records that show he has no Cherokee ancestry.

“It’s been a couple of weeks since that video call, and I’m still reeling,” King wrote in the Globe and Mail. “At 82, I feel as though I’ve been ripped in half, a one-legged man in a two-legged story. Not the Indian I had in mind. Not an Indian at all.”

Canada in recent years has been roiled by false claims of Indigenous identity among prominent figures in the arts, politics and academia. Perhaps best known is the case of Buffy Sainte-Marie, the musician and activist who co-wrote the Oscar-winning song “Up Where We Belong” and appeared regularly in traditional dress on “Sesame Street.” After the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. reported in 2023 that she was born Beverly Jean Santamaria to a couple with Italian and English ancestry in Massachusetts, she was stripped of several awards.

Such claims cause real harm, analysts say, cementing harmful stereotypes and denying actual Indigenous people opportunities in a country where systemic barriers to entry in many fields leave them in short supply.

Suspicions had long swirled about King’s Indigenous ancestry — a fact he acknowledged in the essay. Even so, the revelation has rattled Indigenous communities here and the Canadian entertainment industry.

The Anishinaabe writer Tanya Talaga, in a separate Globe and Mail piece she said she wished she didn’t have to write, called the news “a blow.” For Anishinaabe columnist Niigaan Sinclair, it was a “gut punch,” he wrote in the Winnipeg Free Press, even if King hadn’t claimed Indigenous identity “out of malice.”

Within days, the fallout was coming into focus. King said he would return one award: the National Aboriginal Achievement award for arts and culture. HarperCollins Canada accepted his request to withdraw an upcoming novel from publication, the Globe and Mail reported. The opera planned for Edmonton and Toronto was canceled.

King’s agent did not respond to a request for comment. HarperCollins Canada declined to comment.

In his essay, King said he hadn’t intentionally deceived anyone. But some now question his explanation, saying he should have done more to learn about his identity sooner, given its centrality to his work and image, and are urging him to give up other awards.

“He built his whole career on telling and presenting an authentic Indigenous voice to represent the lived experiences and the realities of Indigenous folks,” said Celeste Pedri-Spade, McGill University’s first associate provost for Indigenous initiatives. His Indigeneity, she said, “was central to all that.”

The poet Daniel Lockhart, a member of the Moravian of the Thames First Nation, says Indigenous people are left with a question that’s probably unanswerable.

“We wonder who else we lost because Mr. King assumed so much material wealth and space that was supposed to be reserved for people in our community,” Lockhart said.

King was raised in Roseville, California, by his mother, who had Greek ancestry. He told the author Margaret Atwood in 2020 that he took a liking to storytelling as a child. His family didn’t have much, he said, so he made up stories, “probably to make myself feel better, probably to try to create a world in which I was the hero.”

He came to Canada in 1980 to work in the Native Studies department at the University of Lethbridge and rose to prominence as a writer of fiction and nonfiction, and as a character on the CBC Radio program “The Dead Dog Café Comedy Hour.”

He has admitted to struggling with how to approach race and identity.

“It’s a difficult thing to navigate, especially if you sort of sit in that border zone, as it were,” he told CBC News in 2020. “I’m Cherokee and Greek: Would it be easier if I was all Cherokee, or all Greek? I don’t know. But it feels as though I’m in a border zone most of the time. It’s not quite this, not quite that.”

In his Globe and Mail essay, King wrote that his father left his family when he was 3 years old. When King was older, he wrote, his mother told him that his father was part Cherokee. In his late 60s, King tracked down his father’s sister in Spokane, Washington. She confirmed his mother’s story, he wrote.

King acknowledged hearing rumors about his Indigenous ancestry, but he mostly put them out of his mind. He recognized, he wrote, that he wasn’t “a good Indian” who spoke Cherokee or who was raised on a reservation, but he took comfort in his family’s story. In October, after whispers resurfaced, he contacted the Tribal Alliance Against Frauds, which he claims were their source.

The group traced his father’s lineage, finding records he says he had been unable to locate. On a November call, it told him his father was not part Cherokee. It was “devastating,” King wrote, “though devastating is too pedestrian a word.”

Robert Jago, a writer from the Kwantlen First Nation and Nooksack Indian Tribe who co-hosted a podcast on false claims of Indigenous identity, wrote in the Toronto Star last week that there had long been suspicions about King, but he was a “nice guy” and investigating further “felt like beating up on Mr. Rogers.”

Canadian institutions have been engaged in thorny debates about what it means to identify as Indigenous, what should be done when false claims emerge and what systems should be put in place to detect and discourage them.

Weeks before King’s essay was published, the Edmonton Opera was grappling with those questions. It had planned to stage the world premiere of “Indians on Vacation” in February 2026. The opera said the project, which had a mostly Indigenous cast, spoke “to an Indigenous story in a way we’re not often privy to.”

Willier, on seeing the listing, wrote to the opera with her concerns. She was granted a meeting with its executive director and artistic director over coffee and found them to be “very understanding.”

“They were eager to learn,” Willier told The Washington Post. “They were receptive, and I think they understood the impact that it would have on the Edmonton Indigenous community.”

Willier said she also contacted King’s agent as the opera debated what to do.

She met again on Nov. 2 with more folks from the opera and Indigenous academics, elders and artists. The Indigenous attendees agreed unanimously that the opera should be canceled.

“We had to express the damage that happens when cultural appropriation is being amplified and celebrated,” said Georgina Lightning, a director, screenwriter and actress from the Samson Cree Nation. “We’ve got so many storytellers. We’re not heard, we have no representation, we have no support, we have no opportunity. Why are we making room for a fraud?”

Opera leaders told them they would bring the matter to their board and lawyers, Willier and Lightning said, but it seemed likely then that the production would be canceled. After it was, but before the cancellation had been announced to the public, they joined a Zoom call with opera leadership and the cast and composer of “Indians on Vacation.”

In that session on Nov. 21, they said, composer Ian Cusson defended King, insisting that he was Indigenous. Some cast members were in tears, Lightning said. Cusson did not respond to a request for comment. Other cast members declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment.

On Nov. 24, the Globe and Mail published King’s essay.

“It was like, ‘Wow,’” Lightning said. “Open-and-shut case.”

Later that day, the opera announced the cancellation to the public, saying it had made the decision “after thoughtful reflection and consultation” with Indigenous people.

“Through these discussions,” the opera said in a statement, “it became clear that moving forward would not align with our commitments to reconciliation, cultural respect and responsible partnership.”

Lightning said that she hoped the controversy would not deter the opera from supporting other Indigenous stories.

“It was emotionally exhausting to go through this process,” she said. “And it was all worth it in the end. Sometimes it’s like, I don’t have the energy to fight this one. But it shows that maybe … when you put energy forth, people will listen.”

The post Acclaimed ‘Inconvenient Indian’ reveals he’s not Indigenous appeared first on Washington Post.