America’s year of independence, 1776, began with virtually all of those living in Britain’s 13 North American colonies content to remain under royal rule so long as they could enjoy the basic rights of British subjects. By year’s end, most Americans with a position on the subject favored separation from Britain. Although it was a year of intense fighting, much that mattered in 1776 happened away from the front lines of combat. The full history of 1776 reveals that the most consequential shift that year was not one of battle lines but of ideology: the rejection of monarchism as a core American value.

The year did not see a fundamental change in the contours of the fight for freedom. The Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill occurred during the spring of 1775. The Second Continental Congress named George Washington to lead an American army besieging British forces in Boston during June and adopted the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking Up Arms a month later—all in 1775, not 1776. Even the American conception of liberty did not change in 1776. The individual rights declared in the state constitutions that year echoed the rights demanded of Parliament in earlier petitions by the colonies and Congress. Slavery did not end in any state during 1776, the status of women stayed much the same, and voting rights remained essentially unchanged.

On the military front, 1776 was the year that the Americans drove the British from Boston and kept them out of Charleston, South Carolina, but lost New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. On balance, despite a small but inspiring year-end victory in Trenton, New Jersey, the Americans ended the 1776 military campaign in a weaker position than they began it. Losing the Battles of Long Island and Fort Washington left thousands of American prisoners of war in British prison hulks and the remains of Washington’s army huddled in Morristown, New Jersey, while the British Army settled into winter quarters in New York. The fighting that occurred during 1776 mattered at the time because it kept the Americans in the war, but the Battle of Saratoga (1777) and Siege of Yorktown (1781) are what brought American victory.

[From the November 2025 issue: Whose independence?]

What did change in 1776 was that Americans decisively turned on monarchism and embraced constitutional representative government as the basis for their liberty and happiness. This required independence. In 1776, a rebellion for rights by willing subjects of British colonies became a Revolution for freedom by people who now wanted their own republican government, run by them. Focusing on battles misses much that mattered in 1776 and still matters today: simply put, that in the United States, “the people” would reign and their elected representatives would rule.

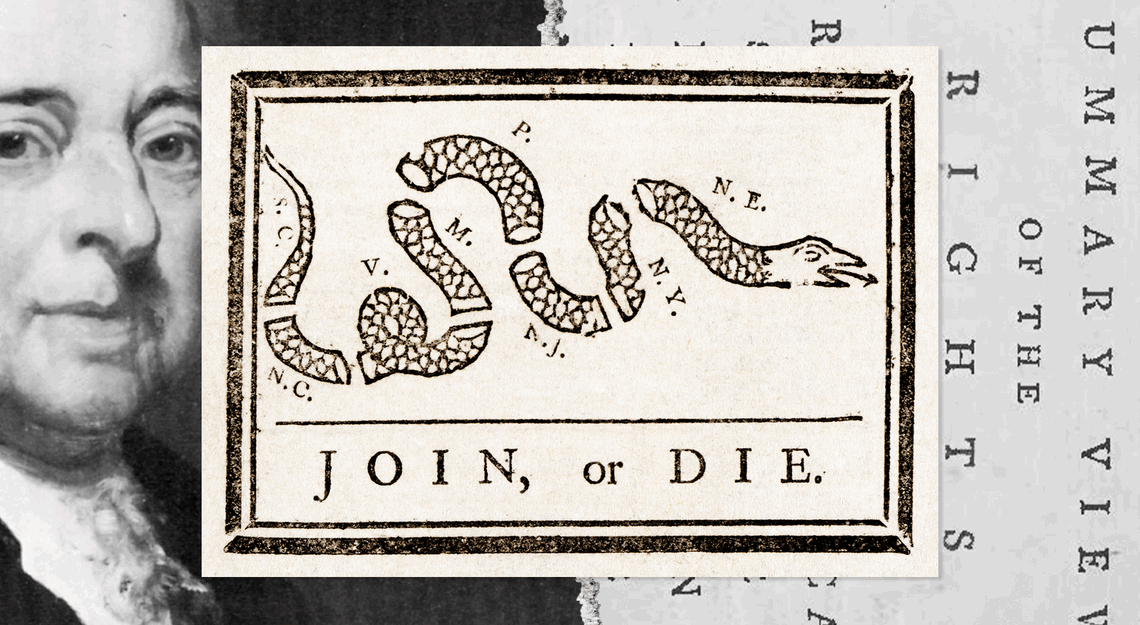

Comparing the words and deeds of 1775 with those of 1776 shows a profound shift in sentiment among the American people. Patriots had been asserting and, in some cases, fighting for their rights as British subjects since the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765, which resulted from Parliament imposing taxes on unrepresented colonists. Parliament refused to back down from the bedrock principle, expressed in its Declaration Act of 1766, that it “hath, and by right ought to have, full power and authority to make all laws and statutes of sufficient force to bind the colonies and the people of America, subjects of the Crown of Great Britain, in all matters whatsoever,” and sent troops to enforce its law in Patriot strongholds such as Boston. Colonists did not question their status as royal subjects but maintained that legislative power over them, including the power to tax, rested in their own elected colonial assemblies.

Thomas Jefferson captured the Patriot view in his 1774 pamphlet, A Summary View of the Rights of British America. “Can any one reason be assigned why 160,000 electors in the island of Great Britain should give law to four millions in the states of America, every individual of whom is equal to every individual of them?” he asks. “Were this to be admitted, instead of being a free people as we have hitherto supposed and mean to continue, we should suddenly be found the slaves not of one but of 160,000 tyrants.” Note Jefferson’s concern about tyranny by Parliament, not by the King. This would change in 1776.

As the conflict deepened, to coordinate their resistance to Parliament, the colonies sent delegates to a First Continental Congress, in 1774, and called a second one for 1775. Before that second Congress met, British troops in Massachusetts clashed with Patriot forces at Lexington and Concord, leading Congress in July 1775 to adopt its Declaration on Taking Up Arms. After noting, “We are reduced to the alternative of choosing an unconditional Submission to the tyranny of irritated Ministers”—which is to say, the King’s ministers in Parliament—“or resistance by Force,” the declaration explains, “We have not raised Armies with the ambitious Designs of separating from Great-Britain” but “in defense of the Freedom that is our Birth-right.” Congress then adopted the Patriot forces opposing the British in Boston as its army and chose Washington to lead it.

Reinforcing the point that these steps were aimed against parliamentary ministers rather than the King, Congress then sent its Olive Branch Petition to King George III, declaring the fidelity of colonists “to your Majesty’s person, family, and government” and asking him to rein in the ministers. Siding with Parliament, the King refused to receive the petition and instead, in August, proclaimed “the colonies in open and avowed rebellion.” Then, in a speech to Parliament on October 27, he vowed to quash the rebellion with more ships, troops, and Hessian mercenaries.

This speech did not reach America until December and was not widely disseminated until January 1776, when it appeared in colonial newspapers. This timing coincided with the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, the first widely read pamphlet proposing American independence. Damning authoritarian governments as “the disgrace of human nature,” Paine calls for popular ones with frequent elections to ensure “their fidelity to the Public will.” The effect was electric. Almost overnight, the King rather than Parliament became the target of colonial grievance, and gaining independence under representative state governments rather than securing rights under a sovereign monarch became the Patriot aim.

Within weeks of its publication, Common Sense became the best-selling and most widely read pamphlet of its day. Offering what his pamphlet depicts as “nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense,” Paine opens and closes by contrasting the dazzling ideal of republican rule under fairly and frequently elected legislators who represented “the public will” against a grim reality of arbitrary rule by authoritarian monarchs. Paine singles out for special scorn the British royal lineage, whose founder, William the Conqueror, Paine depicts as “a French Bastard landing with an armed Banditti and establishing himself as King of England against the consent of natives.” “Monarchy and succession have laid (not this or that kingdom only) but the World in blood and ashes,” Paine affirms in a line that became an American statement of faith. “Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.”

Paine’s words gave voice to an emerging spirit that lifted colonial resistance to imperial tax policy into a global revolution for liberty under law. “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind,” Paine proclaims at the outset. “We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” he promises at the end. In the 80-odd pages in between, Common Sense depicts “liberty and security” as the “end of government,” outlines a democratic one calculated to advance “the greatest sum of individual happiness with the least national expense,” and assures readers that, for such a cause, Americans could prevail against all the force that Britain could muster. Life, liberty, and happiness stand as founding ideals here much as they would in the Declaration of Independence six months later. “The will of the king is as much the law of the land in Britain as in France,” Paine writes in defiance of George III. “In America the law is King. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King.” This became the animating spirit of 1776; it is why that year still matters.

John Adams soon advanced these themes in his preamble to Congress’s resolution urging colonies to form new governments and a pamphlet summarizing his thoughts on those institutions. “Whereas his Britannic Majesty” has “excluded the inhabitants of these United Colonies from the protection of his crown,” Adams’s preamble declares, “it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed, and all the powers of government exerted, under the authority of the people.” This, his pamphlet notes, would require a written constitution for each newly sovereign state. Asserting like Paine that “the happiness of the people, the great end of man, is the end of government,” Adams writes that “the form of government which will produce the greatest quantity of happiness is the best.” Republics do so because they represent the people, he offers, but only by having constitutional structures that assure fair elections and prevent the concentration of “all the powers of government” in any one body or office. Republics, he writes, are governments “of Laws, and not of men.” Only public virtue buttressed by a balanced constitution can sustain them.

Adams closes his pamphlet with a flourish. “When” he asks, had a “people full power and a fair opportunity to form and establish the wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can contrive?” To him and other Patriots, 1776 was less about defeating Britain than about establishing representative governments and securing individual rights. “In truth it is the whole object of the present controversy,” Jefferson writes about the new constitution being drafted for Virginia, “for should a bad government be instituted for us in future it had been as well to have accepted at first the bad one offered to us from beyond the water without the risk and expense of contest.” Along those same lines, the opening line of North Carolina’s 1776 constitution reads, “All political power is vested in and derived from the people only.”

[From the November 2025 issue: The insurrection problem]

Then and thereafter, these new constitutions of 1776 served as footing for the Declaration of Independence, in which Congress affirmed that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” It concludes its list of grievances: “We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, … do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown.” Patriots in New York responded to the declaration’s first public reading by toppling a statue of King George III.

By replacing reigning monarchs and ruling lords with elected leaders, American independence gave impetus to the principle of equality under law. In Britain at the time, legal status and political office came from birth. While purportedly placing even the monarch under the law, England’s fabled Magna Carta conferred rights and power based on rank, with more for barons, less for freemen, and still less for serfs. All were not created equal. Although some Patriot leaders were wealthy and many held political posts before the Revolution, none came from an ennobled or long-established family. Virtually all of them or their recent forbearers earned their wealth and gained their positions in America, where economic and political opportunities existed for free white males. In 1776, most Patriots likely accepted the self-evident truth of the historic phrase in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal.”

Quite obviously, their conception of “all men” was not a complete one. For many prominent Patriots, it did not include Native Americans, enslaved people, and women. Jefferson freed only 10 of the more than 600 persons he held in bondage, and most of those freed were his own children by Sally Hemings. In 1776, when Virginia and Delaware used similar words in their state constitutions, they qualified them to apply only to persons in society, which excluded Native Americans and enslaved Black people. For northern states that used this phrase in their constitutions without qualification, it prodded them toward ending slavery. Indeed, when an enslaved Massachusetts woman known as Mum Bett first heard the phrase quoted from her state’s new constitution, she demanded and received her freedom in court.

In the next century, opponents of slavery and advocates of women’s rights understood the assertions of 1776 about equality under law as foundational to the American identity. In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton began her Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments by paraphrasing the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” In his 1852 speech decrying American slavery, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Frederick Douglass professed to draw “encouragement from ‘the Declaration of Independence [and] the great principles it contains.’” Two years later, after Congress opened the door to slavery’s westward expansion through the much-maligned Kansas-Nebraska Act, Abraham Lincoln stated, “The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska are utter antagonisms.” Such affirmations and others like them demonstrate the ongoing significance of 1776. Its ideals established and sustain American liberty and equality under law. “The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth,” Paine’s Common Sense proclaimed at the outset of that epic year. “’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest.” As members of posterity’s current living generation, we still are.

This article has been adapted from Edward J. Larson’s new book, Declaring Independence: Why 1776 Matters.

The post What Actually Changed in 1776 appeared first on The Atlantic.