Early last month, the White House convened a meeting of right-wing influencers for a livestreamed discussion of antifa and the danger they claim it poses. Over the course of the roundtable, President Donald Trump suggested that protests against him had been organized by mysterious funders, who he hinted could soon be in “deep trouble.” He complained about television networks that were biased against him but praised CBS, whose parent company had recently been purchased by a Trump-friendly billionaire. And he touted an executive order that demanded the Justice Department bring charges for burning American flags. “We took the freedom of speech away,” the president said.

Like so many of Trump’s pronouncements, this was something of an exaggeration: Flag burning is still protected speech under the First Amendment, per a 1989 Supreme Court decision that Trump has no ability to overturn. But Trump’s comment did reflect a deeper truth about his administration’s effort to force an abrupt contraction of American civic space.

During the first 10 months of Trump’s second term in office, the federal government has cracked down on political expression—often understood as the most protected category of speech—with a persistence and viciousness reminiscent of some of the darkest periods of U.S. history. The administration has pushed for the prosecution of the president’s political opponents, fired government employees for taking positions perceived as less than entirely loyal to Trump, and barred certain law firms from working with the government because they displeased the president. It blocked AP reporters from the White House press pool because the wire service refused to refer to the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America.” It has investigated media companies and threatened to withhold merger approvals unless networks get rid of DEI policies; slashed billions of dollars in grants that it characterized as deriving from “immoral” and “illegal” DEI practices; and withheld funding for high-profile universities such as Harvard and Columbia with the goal of forcing their capitulation to the administration’s political agenda. Following the murder of the right-wing influencer Charlie Kirk, in September, the administration called for the repression of left-leaning political views and revoked the visas of six foreigners who had criticized Kirk online. Months earlier, it snatched up and attempted to deport foreign students studying at U.S. universities who had criticized Israel, deriding them as “pro-Hamas.”

These attacks are dizzying in their variety. But they are best understood in the aggregate, as facets of a single campaign to destroy the American public sphere and rebuild it scrubbed of political opposition. In that respect, Trump’s crusade of repression bears a resemblance to the ongoing silencing of dissent in other backsliding democracies around the world, such as Turkey, Hungary, and India. After federal immigration agents grabbed Rumeysa Özturk, a Turkish Ph.D. student at Tufts University, off a Boston-area street—apparently in retaliation for her co-authorship of an op-ed criticizing Israel—a group of Massachusetts members of Congress compared the abduction to the 2020 arrest of a dissident by secret police in Belarus. Cases such as Özturk’s, the representatives wrote in The New York Times, bring the country “closer to the authoritarianism we once believed could never take root on American soil.”

[Read: We study repression in Turkey. Now we see it here.]

Yet the Trump administration’s effort to crush dissent is not without American precedent. On a single day in 1920, the Justice Department rounded up thousands of people for deportation because of their supposed Communist sympathies, though many had little or nothing to do with the Communist Party. In Boston, not far from where Özturk was arrested, some “aliens” were handcuffed and chained together while authorities marched them down the street in front of photographers. Those raids were the peak of what is now known as the first Red Scare—a period of paranoia about Communism and anarchism that began around the time of America’s entry into World War I. Three decades later, the country plunged into the second Red Scare, a rampage against supposed Communist plots often remembered by the name of its most famous proponent, Republican Senator Joe McCarthy. Accused “reds” were hauled in front of Congress, lost their jobs, and retreated from public life.

Today, the country might be said to be in the midst of a third Red Scare. It is shaped by the legacies of the previous two, in terms of both its substantive anxieties and the techniques of its inquisitors. Our new Red Scare, like the first, is obsessed with immigration and the potential of left-wing political violence—then, anarchists and Communists; today, the imagined, shadowy antifa. Like the second, it is coupled with unease about changing norms regarding gender and sexuality. The anti-Communist fervor of the late 1940s and ’50s generated suspicion of women in positions of authority within government and drove thousands of gay and lesbian government employees out of the federal workforce, in what the historian David K. Johnson termed the “Lavender Scare.” Now the Trump administration’s anxiety about the erosion of rigid gender roles manifests in its disdain for feminism—early in the administration, agencies removed material on women’s achievements from their websites—and in its aggressive hostility toward transgender people, whom the government has pushed out of the armed forces and erased from National Park Service websites. Cam Silver, a political scientist at the City University of New York, described this campaign as a “Sapphire Scare,” after the blue of the transgender-pride flag. “The word ‘woke’ now performs the job that ‘communism’ did in the 1950s,” Silver told me over email.

In a country that prides itself on independence and freethinking, key pillars of civil society—universities, law firms, businesses—have proved quiescent in the face of a campaign to squelch dissent. The political scientist Steven Levitsky, a prominent scholar of democratic decline, graded the early response of civil society to Trump’s onslaught as a “D-minus.” Yet as methods of repression have evolved over the past 70 years, so, too, have methods of resistance. Trump’s campaign of repression is therefore in the strange posture of pushing more forcefully to silence dissent than the first and second Red Scares ever did, while also facing far more organized opposition—and a public that sours on the government’s efforts the more that Trump doubles down. American civil society is in some ways weaker than many had hoped, but it is also stronger than it once was.

The first and the second Red Scares both drew their power from fear. Although President Woodrow Wilson ultimately was able to deport only a small portion of the noncitizens arrested during the first Red Scare, those numbers don’t capture the “intimidation resulting in self-censorship” that spread after the raids, Julia Rose Kraut explained to me; she is a legal historian and the author of Threat of Dissent: A History of Ideological Exclusion and Deportation in the United States. In June 1917, in a precursor to the Trump administration’s furor over student protests at Columbia University, three students were prosecuted for printing anti-draft pamphlets. (My great-great-uncle was among them.) Then, as now, government harassment was a warning to others not to make too much noise. Similarly, in the second Red Scare, after a group of prominent screenwriters, producers, and directors—the “Hollywood Ten”—were questioned about suspected Communist sympathies by the House Un-American Activities Committee, the movie industry began quietly paring back film scripts to avoid anything too left-wing.

Contemporary First Amendment law refers to this dynamic as a “chilling effect,” and there is a great deal of it in the United States right now. Testifying in a legal challenge brought by the American Association of University Professors against the Trump administration for its attempted deportations of student protesters, multiple green-card-holding professors said that they had ceased speaking publicly and attending conferences for fear of attracting the administration’s attention. In Texas, where several professors and university administrators have been pushed out or otherwise punished following MAGA outrage, some academics say they are anxious about the potential career repercussions of teaching subjects as previously anodyne as the women’s suffrage movement and gender-bending comedies by Shakespeare. In Tennessee, a retired police officer spent more than a month in jail after sharing a Facebook meme in response to Charlie Kirk’s death. Large law firms are wary of affiliating themselves with politicized causes, lest they be targeted by Trump’s wrath—making it more difficult for would-be plaintiffs to secure pro bono legal representation. Chat with a journalist whose work touches on domestic politics, and you will likely hear complaints that many sources are now far less likely to go on the record for any story critical of Trump.

The historians, lawyers, and scholars I spoke with were in marked agreement that the current moment is not just comparable to but even more damaging than previous Red Scares. Within higher education, today’s crackdown is “worse than McCarthyism—much worse,” Ellen Schrecker, a historian and the author of No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities, told me. Then, she explained, individual academics were scrutinized and fired for Communist ties. But today, the country is experiencing a “frontal attack on everything that has to do with universities and colleges,” Schrecker said.

This assault on higher education is best understood as a means of destroying a locus of political opposition. With growing political polarization along educational lines, college-educated voters have become more likely to vote for the Democratic Party. Trump’s solution is an attempted dismantling of the institutions that helped produce these voters in the first place—and a symbolic attack on institutions of knowledge and expertise that are inherently at odds with Trump’s model of governance by know-nothingism.

[Read: Trump’s crime crackdown isn’t holding up in court]

This overtly partisan cast distinguishes Trump’s campaign to crush dissent from America’s fits of anti-Communist paranoia in the early and mid-20th century, which were more bipartisan affairs. The House of Representatives twice refused to seat the socialist Victor Berger in Congress by near-unanimous votes in 1919 and 1920, objecting to his anti-war views. Although the second Red Scare is today associated with McCarthy’s culture-warring conservatism, a key early step was Democratic President Harry Truman’s establishment of a loyalty program to root out “subversive” federal employees. Likewise, although the first and the second Red Scares spiraled out of control, they began as responses to genuine shocks: the Russian Revolution in 1917 followed by a string of anarchist bombings, and the deepening tensions amid the advent of the Cold War in the late ’40s. As political violence again grips the country, the Trump administration seems less interested in lowering the temperature and more interested in wielding those threats as an excuse to quiet political opposition.

The government’s legal tactics have changed since the first and second Red Scares, in large part because the protections offered by the contemporary First Amendment are far more robust. Today’s law of free speech itself evolved “as a reaction to the problems of the McCarthy Era,” the First Amendment scholar Genevieve Lakier recently wrote. For this reason, Trump would have far more difficulty, say, prosecuting Columbia students simply for handing out pamphlets. The evolution likewise explains why the administration has so far struggled to come up with legal tools for attacking antifa—the nonexistent organizational structure of antifa notwithstanding—and why it has relied so heavily on paper-thin allegations of anti-ICE protesters assaulting immigration officers: Criminalizing political activity is out of bounds, full stop.

But at the same time, the Trump administration has proved skilled at exploiting the weak points of First Amendment law—a campaign most visible in the president’s attack on pro-Palestinian foreign students, such as Özturk. Although a 1945 precedent establishes that immigrants within the United States enjoy First Amendment protections for freedom of speech and of association, the government’s expansive powers of immigration enforcement have left noncitizens far more vulnerable to ideological scrutiny. In this sense, the Trump administration may have gone after noncitizen students with such force in significant part because they made for easy targets. Along similar lines, the Department of Homeland Security recently revoked the visa of Sami Hamdi, a British Muslim political commentator critical of Israel, and detained him for deportation—ostensibly for “supporting terrorism,” an allegation for which the government provided no evidence—while he was in the middle of a U.S. speaking tour.

The administration is also armed with post-9/11 legal precedents that cut into speech protections—even for citizens—on issues that can be framed as relevant to foreign policy or national security. When U.S.-based lawyers and human-rights advocates challenged the administration’s sanctions on the International Criminal Court, arguing that Trump had violated their First Amendment rights by barring them from working with the court, the Justice Department pointed to a 2010 Supreme Court decision that allows restrictions on Americans’ engagement with designated foreign terrorist organizations. For related reasons, Trump’s supporters have toyed with the idea of somehow designating the poorly defined antifa as such a group, a move that could effectively criminalizing dissent. (In September, Trump issued an executive order declaring antifa to be a domestic terrorist organization, but this designation has no legal meaning.) The fact that the administration has not yet done so speaks to the factual and legal shakiness of this argument.

The flip side is that political speech unambiguously by Americans, about America, receives strong legal protections. It’s here that Trump has come to rely on more indirect methods of pressure—chiefly involving the withholding of money. Universities are far more vulnerable to presidential pressure today than they were during the second Red Scare, thanks to the massive amount of federal funding that the government has poured into higher education over the past 70 years. Trump is now dangling the potential loss of that same funding over schools to get them to bend to his will, and in many cases it is working in his favor. Columbia, Brown, Cornell, and the Universities of Pennsylvania and Virginia have all brokered agreements with the administration requiring various degrees of coordination with the government. The Federal Communications Commission, meanwhile, has leveraged a consolidated media landscape by threatening to withhold merger approvals unless companies pledge fealty to Trump. FCC Chair Brendan Carr approved an $8 billion merger between the media giants Skydance and Paramount, which owns CBS, only after Paramount handed Trump $16 million to settle a baseless lawsuit and Skydance agreed to install a Trump-friendly ombudsman at the network.

(Brendan Smialowski / AFP / Getty)

Carr’s self-appointment as chief censor is a sharp reversal from his previous insistence that “censorship is the authoritarian’s dream.” Like many others on the right, he spent President Joe Biden’s term in office warning about supposed government repression of conservative ideas. Hypocrisy aside, this recent history has aided litigants who challenge attacks on free expression far more blatant than anything the Biden administration ever dreamed of. In 2024, the Supreme Court ruled that New York regulatory authorities had breached First Amendment protections by threatening and cajoling insurance agencies against doing business with the National Rifle Association. Again and again, judges have pointed to NRA v. Vullo to argue that Trump’s bullying of law firms and universities is likely unconstitutional.

Right-wing cries for retaliation following Kirk’s murder almost resulted in Vullo’s biggest moment yet. After the late-night host Jimmy Kimmel criticized MAGA’s response to the assassination, Carr appeared to threaten companies that didn’t “take action” on Kimmel. Disney promptly pulled Jimmy Kimmel Live from ABC—a textbook example of the dynamic prohibited by Vullo. Kimmel, arguably, could have sued. Instead, public outrage exploded. Cancellations of subscriptions to Disney’s streaming services doubled following a campaign encouraging consumers to abandon the company, according to the data-analytics company Antenna. Just shy of a week later, Disney returned Kimmel to the air. The broadcasters Nexstar and Sinclair, which are both awaiting the FCC’s sign-off on acquisitions, initially refused to air the show but allowed it back after just a few days.

[Read: The Constitution protects Jimmy Kimmel’s mistake]

When I spoke with Schrecker about her study of the second Red Scare, she pointed to Kimmel’s victory as an indication of the difference between the McCarthy era and today. During McCarthyism, “there was essentially no opposition,” she told me. “People either supported the purges, or else they were too afraid.” One representative anecdote in No Ivory Tower describes a graduate student at the University of Chicago who, during the ’50s, was unable to persuade frightened colleagues to sign a petition—not about any politically sensitive topic but for the university to install a vending machine in their laboratory. In contrast, after Disney pulled Kimmel from the air, petitions and calls for boycotts blossomed. The ACLU launched a campaign to “defend free speech,” and hundreds of actors and artists signed on.

Reading No Ivory Tower, I was struck by how little organizations such as the ACLU and the AAUP, the professors’ association, did to protect academics from McCarthy’s censorship. Today, both organizations have been aggressive in pushing back. The ACLU recently announced that it has filed more than 100 lawsuits against the second Trump administration; in addition to its lawsuit over attempted deportations of foreign students, the AAUP has filed suits against a variety of the administration’s efforts to target higher education. Many civic institutions have buckled under pressure, but the ruckus made by the others is far louder than any of the muted pushback against McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The institutions that initially caved have, paradoxically, tended to be bigger and wealthier—Paramount, Columbia University, prominent law firms. Such organizations “are in many instances actually more vulnerable, because they have more pain points—federal grants, licenses, merger approvals—that the Administration can use to exert leverage,” Fabio Bertoni, The New Yorker’s general counsel, writes in a reflection on why elite law firms gave in to Trump. To some extent, this is a story about the increased size and role of the federal government in everyday life since the days of the last Red Scare, and what happens when that architecture is turned into a weapon.

But it is also a story about another set of crucial changes in American life since this period: the maturation of litigating organizations such as the ACLU, along with legal and cultural shifts that have made Americans more comfortable with the idea of taking the government to court. In the 1910s and ’20s, and even through the ’40s and early ’50s, the Supreme Court fielded relatively few cases concerning individual rights. This changed with the civil-rights movement and the “rights revolution” of the ’60s and ’70s, when the Court became far more open to validating such claims. Charles Epp, a professor at the University of Kansas who researches law and social change, has argued that growing civil-liberties organizations became a “support structure” for these judicial shifts—and today, that support structure is the strongest it has ever been. The organizations that emerged from that tradition have been most forceful in responding to Trump’s abuses, in many cases by representing individual plaintiffs or smaller groups that lack the vulnerabilities of major institutions. The challenge to Trump’s treatment of foreign students, for example, was brought by the AAUP—itself represented by the Knight First Amendment Institute, a newer civil-liberties organization (for whose website I have written in the past)—rather than by universities themselves.

“Civil liberties organizations have vastly more capacity” than they did in the ’50s, Epp explained over email, and that growth “helps to explain why the litigation against the Trump initiatives is so much more widespread than in the 1950s and early 1960s.” Sherrilyn Ifill, the former head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, told me that she understands the work done by these organizations today to be adopting the “template that was created by those who practiced civil-rights law” in the movement’s early years, most prominently at the LDF itself. In the mid-20th century, the LDF and other organizations like it pioneered the use of litigation as a means of resisting authoritarianism and racial repression, which intensified during both Red Scares. Litigation against contemporary attacks on democracy follows in that tradition. “Some of the institutions that have caved are simply ones that had never been tested with this kind of challenge,” Ifill said. “But for us, that’s kind of baked into the pie.”

[Read: Jimmy Kimmel ran right at his critics]

The rights revolution helped build a culture that today has led to widespread resistance to Trump’s crackdown—grassroots upsets of the sort that led to Kimmel’s return and that power both the mass demonstrations such as “No Kings” and the litigating organizations via donations and other support. The internet also helps opponents of the administration find support, connect with one another, and organize protests. Gay and lesbian Americans pushed out of government service during the Lavender Scare had little infrastructure to turn to for support, but the gay-rights movement blossomed in the subsequent decades. Silver, at CUNY, contrasted ongoing litigation and protests about the treatment of transgender Americans with the “silence and shame” of the ’50s: “The erasure cannot happen in the dark the way it did before.”

Other hints of opposition have arisen from less predictable quarters. The American right’s embrace of free speech as a rallying cry in recent years, drawing on First Amendment law shaped by both the response to McCarthyism and the civil-rights movement, led some Trump supporters to voice discomfort with outright calls to suppress opposing views in the aftermath of Kirk’s murder. “I think it is unbelievably dangerous for government to put itself in the position of saying we’re going to decide what speech we like and what we don’t,” Republican Senator Ted Cruz said on his podcast after Brendan Carr threatened Disney over Kimmel.

Public support for the first Red Scare collapsed after the Justice Department embarrassed itself by issuing dire warnings about a May 1920 violent left-wing uprising that never occurred. The second Red Scare ran out of Communists to harass as the nation’s attention shifted toward the civil-rights movement. Today, the third Red Scare is not popular: 57 percent of Americans oppose increased involvement by the federal government in higher education, 61 percent believe that Trump has gone “too far” in pressuring media organizations as a response to unfriendly coverage, and 55 percent strongly or somewhat disapprove of Trump’s handling of free-speech issues; on the latter, data showed a 14-point decline even among Republicans from March to September.

The question is what damage will be done anyway. Canceling a Disney+ subscription is the sort of consumerist engagement with politics that’s comfortable and familiar for average Americans. Standing up on behalf of individuals and institutions they don’t have a consumer’s relationship with is a more difficult task. And litigation can carry only some of that weight. The week after Nexstar and Sinclair relented and agreed to allow Kimmel back on air, Judge William Young issued a lengthy ruling in the AAUP’s challenge to ideologically motivated deportations, holding that the Trump administration’s treatment of noncitizen students violated the First Amendment. Despite his defense of the courts as the “major bulwark of our right to free speech,” the judge worried that litigation would be too “ponderously slow” and “crushingly” expensive to adequately protect free expression. And a court ruling alone will not dispel the fear that Trump has engineered, especially given the White House’s willingness to disregard judicial orders.

All the while, civic space in America is more guarded, more cramped, and less free. The effect is not just a professor who chooses not to teach a potentially controversial subject, but also all of the students who don’t have a chance to learn, and the scholarship and art they aren’t inspired to produce. Even if activists can fight back against Trump’s censorship campaign, any eventual accounting of our current moment will likewise need to attend to the careers that were not pursued and the things that were not done and not said. The damage done by this administration exists not just in overt censorship and destruction but also in its negative image, a topography of silence and absences.

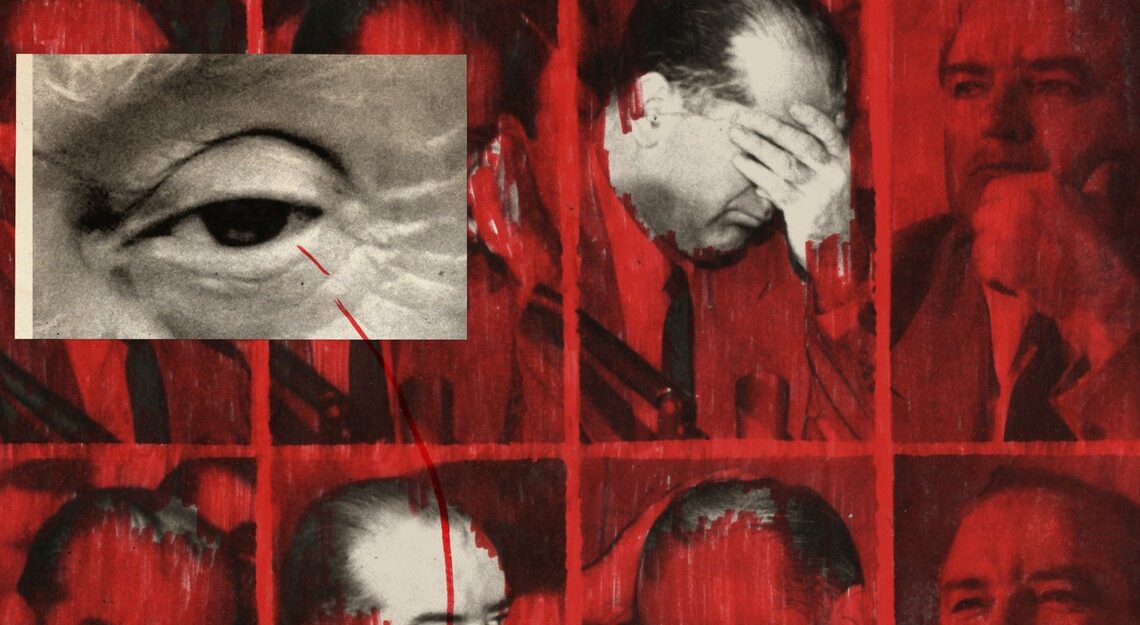

*Illustration Sources: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds / AFP / Getty; Bettmann / Getty.

The post The First Amendment Won’t Go Quietly appeared first on The Atlantic.