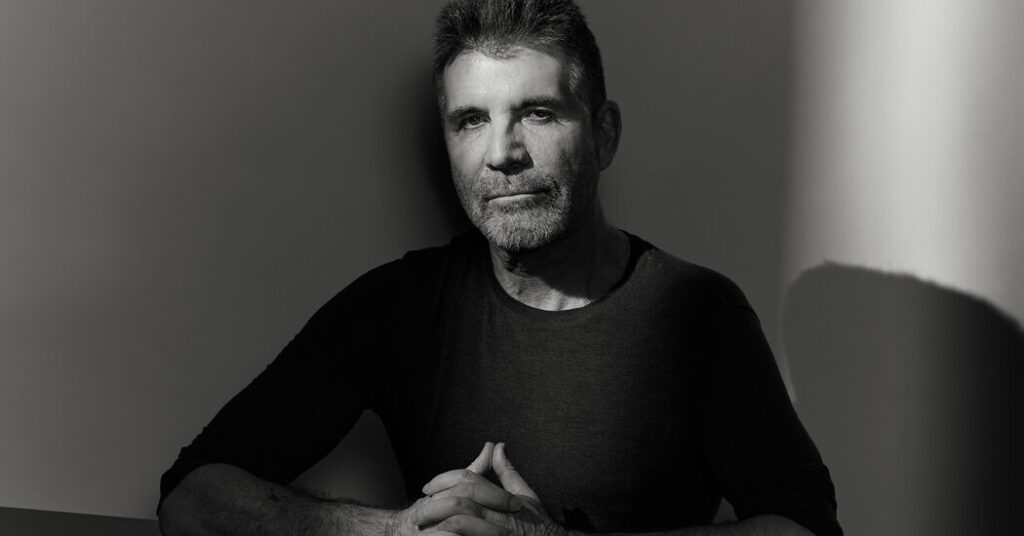

Simon Cowell, the famously caustic judge from “American Idol” and “X Factor,” has mellowed. Part of that is age (he’s now 66), but he has also suffered the loss of his parents, become a father, gone to therapy and more recently grappled with the death of Liam Payne, whom he discovered on “X Factor” and cast in the megafamous boy band One Direction. So when I met Cowell at his home in southwest London this month, I found him in a reflective mood.

The music mogul started his career in Britain as a talent scout and became known for putting out popular novelty records based on TV shows like “Teletubbies” and “Power Rangers” — music that his label peers used to sneer at. He had his first hit single with the artist Sinitta in the 1980s and his first boy-band success with Westlife before becoming a judge on all the shows (“Idol,” “X Factor,” “Britain’s Got Talent,” “America’s Got Talent” and more).

Cowell is now thinking about his legacy. His latest project is a Netflix documentary series called “Simon Cowell: The Next Act.” In it, Cowell goes back to his roots, auditioning and training a group of teenagers to be in his new boy band. The series shows Cowell’s more nurturing side as a family man and a builder of talent, but also his desire for relevance: It has been several years since Cowell launched artists like Camila Cabello and Susan Boyle from his competition shows, and he is trying to prove to himself, and to people who know him only as the guy mouthing off behind a judging desk, that he can still make a hit (even though he doesn’t have a phone and hates the main driver of new music, TikTok).

I don’t really know if Cowell can pick yet another winner or if the world even wants a boy band that isn’t K-pop, but to me that’s almost beside the point. What interested me most in talking to Cowell was his evolution away from his harsh public persona and what that says about him and the broader culture that he helped shape.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Amazon | iHeart

I read that [early in your music career] you boasted that you would figure out what was going on not by going to dingy shows in basements but by reading the storied British tabloid The Sun. You ended up becoming well known for signing acts that a lot of people saw as gimmicky: the Power Rangers, WrestleMania. Where do you think that came from, that understanding of, Let’s take what’s popular and not be precious about it and put it out into the world? Well, all I was thinking was: I’ve got to keep the lights on. I’ve got to get paid. A lot of the A.&R. guys had jobs because they thought they were cooler than everybody else, but a lot of them were just idiots. They thought they were cool, but they were just guessing. And if you dared to play something they didn’t like, they used to sneer at me. When I knew the wrestlers had sold out Wembley Stadium in 30 seconds — that’s 80,000 seats — I just went: Well, whoever loves wrestling, there’s a lot of music on these shows. I think they’re going to buy the record. But I actually liked those records myself. They’re catchy. They’re fun. Don’t take it too seriously.

You also had plenty of flops and a few missed opportunities during this period: the band Take That and then Kylie Minogue. Was that your biggest regret? My biggest regret was probably the Spice Girls. They were mentioned in an A.&R. meeting. They were called Spice then. And somebody said, “We’re hearing about this band called Spice.” Two of the A.&R. guys held their hands up and said, “We’re on it.” So I’m thinking, OK, I’m too late. And then by chance, a few weeks later, I went to a meeting, and the girls happened to be in a van, and they knew who I was. I don’t know why or how, but they just did. Dragged me into the van and played me the demo of “Wannabe,” and I’m like, Oh, my God, they’re going to be huge. Got in my car, got back to the office, called the manager, and I said, “If you haven’t signed a deal, I’ll double whatever you’ve been offered.” And he said, “We signed yesterday.” Now I don’t know whether that was true or not, but that was really, really hard.

Let’s fast forward to “American Idol.” Reading your autobiography, one of the things that jumped out is that you really struggled with how the public was initially perceiving you. That bluntness that you brought to the show — once it became a megahit, you started reading the feedback, and it caused you to doubt yourself and later be nicer on the show for a little bit. I don’t remember this period, by the way. I don’t think you were ever particularly nice on the show, but you clocked that it made the show seem inauthentic. I wasn’t trying to be a [expletive] on purpose. All I wanted with these shows was to find successful artists to sign to the label. So when all these people were coming in and they couldn’t sing, I would be like when I used to audition people and someone would come in and they can’t sing. We would say after 10 seconds, “You can’t sing.” Not, “You’re going to be brilliant.”

There are a lot of Simon Cowell insult compilations online. You told singers they had invented a new form of torture. You made some fat jokes. You had a common one that they were the worst singer in America. Lulu, do we have to go through this?

Yes, we have to go through it. The camera would cut to people looking absolutely crushed. What is the line between bluntness and humiliation? That’s why I changed over time. I did realize I’ve probably gone too far. I didn’t particularly like audition days, because they’re long and boring. I would get fed up. And of course, out of a hundred nice comments, what are they going to use? They’re always going to use me in a bad mood. I got that. What can I say? I’m sorry.

What are you apologizing for, exactly? Well, just being a [explicit].

It also made good TV and made you an integral part of what made that show work. Yeah. That was then. I’m not proud of it, let’s put it that way. I never look at this stuff online, so when I hear about these clips, I’m like, Oh, God. But then again, the upside is that it made the shows really popular worldwide.

It also launched the career of Ryan Seacrest. I’ll be honest: I am mystified by how he is so ubiquitous and so popular, and I wanted you to explain it. I can’t really answer that one. He does work hard.

A lot of people work hard. He was very, very ambitious. I didn’t follow his career, so I don’t know what he’s done. We rarely talk now. He was very steely about his career — wanting to be famous. This massive, massive desire about being, you know, very famous.

Eventually, you left “Idol” to launch “X Factor” in the U.S., which was your own project, and you recruited Britney Spears to be a judge. At the time, she was under a conservatorship. What did you understand about her mental state and about what was going on around her? Somebody said, “Britney would be interested in working with you.” And I said, “Well, would she talk to me on a call?” Because I thought, It’s never going to happen. “Yes, Friday night, 8 o’clock. She’s going to call you.” On the dot, she calls, and we spoke for two hours. She was so fun, engaged, passionate, interesting. She just really, really wants to do it, I think for the right reasons, which was to be a mentor. I’m like: Brilliant. I want a second call, because maybe this was a fluke. So we have a second call, and it’s even better. I thought: Wow, whatever I’ve heard about her, she is so smart, so nice, so friendly. I think we’re going to get on really, really well.

Cut to: We do a press launch, and Britney’s there and she doesn’t look that happy. And I said, “What’s the matter?” She said, “I didn’t realize there was going to be so much press around.” And I went, “Well, it is a press launch.” And then on the show, she really struggled with saying no to people. Just didn’t like it. The first day I sat with her, and I said: “Look, there’s two choices. If you really don’t want to do this, I’ll get you out of it. Or you’ve got to understand — I can’t put 200 people in the final, which means obviously we are going to say no to people.” I got to know her when she came over to my house one time, and we just talked and talked, because I really wanted to get inside her head. Was she happy? Was she unhappy? She wasn’t happy. That’s what I took away. It was like two different people, Lulu.

She wrote in her memoir that she absolutely hated doing the show. Did she? That’s a shame. I did say to the network, “I don’t know if she wants to do it, and if she doesn’t, we’ve got to give her the option of being able to leave.” No one was forcing her. She also mentioned to me how much she didn’t like pop music. She was into a different kind of music. So I think she probably struggled with mentoring the artists.

Your other huge success happens around this period: One Direction. You put the band together from a group of kids who auditioned for “X Factor.” I just watched Liam Payne’s audition when he was 16. You give him a standing ovation, and he’s got this beautiful smile and he’s so excited about everything. What do you remember about them at the very beginning? Liam had auditioned for me when he was about 14, 15. He was very young, and he got quite close to making the finals. I remember having to say to him: “It’s just not your time. However, there’s something about you I really like. Will you come back again?” He came back two years later, and he nailed it on his audition. For whatever reason, he and a bunch of others just didn’t do so well in the second part of the competition, and I remember having to say no to a bunch of them, including Liam. And I thought, Christ, I’m going to say no to him for the second time? And then we went, What if we put him with him, with him, with him? It took about 20 minutes, honestly, to make the decision.

In your new show, you’re looking for a new boy band to launch, and in the midst of filming, you receive the news of Liam’s death. Can you tell me how you heard and what you did to process the loss? And I know this is painful, so thank you. Of course we’re going to talk about it. Somebody who works with me very closely came into my room. I was up in the north of England, and I could tell by the look of her face that she was upset. She said, “Sit down,” and she told me. And it was like — wow. It was a bit like I felt when I heard the news when my dad passed away. It’s very difficult to put into words how you feel. It’s just shock. At that point, you’re not really thinking clearly. I just remember saying: “I really need to speak to his mum and dad. Can you get them on the phone as soon as possible please?” Because, God, as a parent, what that must have felt like. I knew his mum and dad, and I wanted to reach out, just to say how I felt. It was just awful, awful. And I’d seen him like a year before in this room. I remember seeing him walk into this room and saying: “God, you look amazing, Liam. What have you done?” “Well, I’m going to the gym” and blah, blah, blah. We talked about his son and how much it means to be a dad. And I was talking to him about there’s more to life than just music; you’ve got to a point in your life where you’ve got choice now, etc. We just hung out as friends. That’s why I was so shocked and surprised when I heard the news.

Since that happened, there has been a lot of reporting on One Direction, the drugs, the alcohol. Liam said on the podcast “Diary of a C.E.O.” in 2021 that, and I’m quoting here: “When we were in the band, the best way to secure us because of how big it got was just to lock us in our room. And of course, what’s in the room? Mini bar.” He talked about struggling. Did you know about that at the time? A little bit. There was stuff I never would have spoken about then, private conversations and advice I tried to give him, which is what comes with fame, etc. But you’re signing a lot of artists, and when you sign an artist, my role is, essentially, get them with the right production team, get the managers and try and make them successful. But at the same time, I probably had about 20 artists on my books at the time. It is a little bit like they leave the nest. You always say you’re available when you need to be, but you can’t follow them everywhere. If I could go back in time to that one day when he was in my house here — obviously, you always think about things like that. What if I’d said this? What if I had said that? But there’s only so much you can do with any artist. If you just have one artist in your life, maybe, but I’m not a manager. My job is to run the label. And you just hope that they are successful and happy.

But when you signed them, they were kids. It must be a different type of relationship that they have with someone like you, who was also a judge and brought them together. Is it a complicated role you have with someone who is so young? It’s always complicated. I don’t know whether it’s more complicated when they’re young or when someone who has had success then hasn’t had success and comes back and wants a second chance. I mean, every time it’s different. Every artist is different. Everybody has the same ambition, which is they come on our shows or they want to work with me because their dream is to be successful. We made these shows because I understood, and still do, that there’s always someone out there waiting to be discovered if you actually look. The chances of getting well known are minute. And then, like I’m doing now with young kids, you ask yourself: Is it a good thing or not? Without this show I’m doing, would they be discovered? I don’t think so. Is it something they want to do? Yes.

For many people, what happened to Liam was a sign of how toxic fame can be. What is the lesson you take from it? It’s very difficult, because I honestly don’t know what is harder: trying to be famous or managing your fame. Both are equally difficult. I can say this about myself: I made my own choices. Not every day has been amazing, but I’m glad I did what I did. I made the decision to do something different in my life, and it comes with pressure, a lot of stress, but I signed up for it because obviously there was something inside of me saying, I want to be well known. And I would do it all over again.

We all know that it is harder to have your finger on the pulse as you get older. Are you worried about that? Because you do note in the new show that you’re in your 60s trying to figure out what teenagers today want. I think the biggest thing really is the amount of time since my last band to this time — and in between, K-pop’s arrived, social media, TikTok is everywhere, and that wasn’t a huge factor then. So the change in 10 years is ginormous.

There has been a lot of discussion in the music industry about artists owning their work. The big example being, of course, Taylor Swift. Artists say: “We’re the ones singing. We’re ones in front of the microphone. Shouldn’t it be ours?” In other conversations, I’ve heard you say that you regret not owning the One Direction name. How do you square that? I think it depends on the circumstances. If a band has formed themselves, and they come to me and say, “We want funding and for you to be the label,” like I used to do, I get it. They did it. If I was part of putting everything together, it’s almost like you’re part of the band.

Over the years, there have been complaints about contracts, where some artists said they actually didn’t make any money when they signed with your company because of low royalty rates. Did you think the contracts were all fair? Well, I didn’t really get involved in those negotiations. If you asked me what anyone’s royalty was, I actually couldn’t tell you. You’d have to talk to both sides, I suppose — the people who are happy and unhappy. Some people were happy. I guess some people are unhappy. That’s life. But I don’t think it was unfair, really, no.

Your authorized biography, which came out in 2012, made it pretty clear that you used to party pretty hard when you were younger, that you were famously adverse to commitment, a man about town. You’re now part of this family unit. You have a long-term partner, Lauren, and your son, Eric. You’ve described having Eric as pulling you out of this very dark downward spiral that you were on after your mother died. I always suffered from depression. And I’d got to a point where my life, my career was going great, but for whatever reason, I was just unhappy. Really unhappy. You know that expression: Is this as good as it gets? I was feeling a bit like that. Everything just felt monotonous. And then, it was like my life changed when he was born. Everything started again.

What did you do, practically speaking, to get yourself to a different place? I used to work sometimes until 7 in the morning. I found that time, from 1 to 7 in the morning, weirdly peaceful. I didn’t get up until the afternoon, so I never saw the morning. I hadn’t seen the morning for years. I actually used to think, God, how could people work in the morning? It just felt weird to me. And then when Eric was about 2, he came in one day, and it was about 2:30 in the afternoon, and he went, “Dad, what are you doing asleep?” And I went: “God, he’s right. What am I doing asleep? I’ve got to readjust.”

It does appear that you’ve softened. Would you say that that’s accurate? Yeah, I would say that. I think I’m more confident in myself now.

I wonder what you make of the fact that the rest of the world has gotten more vicious? I sort of live in a bubble, if I’m being honest with you. I don’t have a phone, and I don’t read anything online. I don’t read newspapers.

You don’t watch TikTok, Instagram, nothing? Nothing. I’m really genuinely oblivious, and I do it for a reason: because I’m happier that way. When you ask me about being softer now, I think maybe part of the reason is that I just don’t get caught up in anything. I don’t want to change that.

You’ve said before that you wanted to be cryogenically frozen. Is that still true? So, yes, I did think for a while: We’re all going to eventually, unfortunately, die. What if then I’ll just freeze myself? That was before I was a dad. Then someone told me they chop your head off, and I think your brain’s frozen. So then the idea of coming back as some kind of robot in 3,000 years time, it’s like: Forget it. No. I’m not interested. I do believe in God, and I really do hope and believe that there’s something good that happens afterward. I don’t know what it is. My mum had a lot of faith, which genuinely made her happy. And I started to think a lot about that. Not because I’m getting older or I’m going to die tomorrow. Just, does it make me happy? Actually, yes, it does.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations. Listen to and follow “The Interview” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, iHeartRadio, or Amazon Music

Lulu Garcia-Navarro is a writer and co-host of The Interview, a series focused on interviewing the world’s most fascinating people.

The post Simon Cowell Is Sorry, Softer and Grieving Liam Payne appeared first on New York Times.