The shooting of two National Guard members in Washington, D.C., shocked Americans on Wednesday, but not everyone was surprised.

“I knew this would happen,” a member of the California National Guard texted The New York Times as news spread, speaking on condition of anonymity because he did not have authority to comment publicly.

As part of the force sent to Los Angeles this summer to assist in the president’s immigration crackdown, the soldier, who has served in the Guard for six years, said he and his commanders worried that the assignment “increased our risk of us shooting civilians or civilians taking shots at us.”

That concern, which was echoed by at least two other California Guard members, was well known, including in the U.S. capital, where the two members of the West Virginia National Guard were critically wounded around 2:15 p.m. by a lone gunman near the White House, according to the Washington Metropolitan Police Department.

According to internal directives distributed to National Guard troops in Washington, D.C., in August, commanders warned that troops were in a “heightened threat environment” and that “nefarious threat actors engaging in grievance based violence, and those inspired by foreign terrorist organizations” might view the mission “as a target of opportunity.”

“Additionally, civilian populations with varying political views may attempt to engage,” one memo instructed troops on Aug. 28.

The memo, filed with court documents as part of a lawsuit by the attorney general in Washington, D.C., Brian Schwalb, against the Trump administration, said that local law enforcement agencies had agreed to increase patrols in the area where the troops were staying, but advised them to travel in pairs, change into civilian clothing when they were off-duty or away from military lodging, and immediately report any suspicious behavior to superior officers or local authorities.

Another memo, dated Aug. 12, from D.C. National Guard commanders outlining the deployment’s objectives and attendant risks, said that the mission ”presents an opportunity for criminals, violent extremists, issue motivated groups and lone actors to advance their interests.”

Part of the case by city officials was that the presence of troops untrained in law enforcement was endangering not only the public but also other law enforcement officers and the National Guard troops themselves. Justice Department lawyers countered that the risk of deadly harm was “speculative.”

“This has been going on for 10 weeks. There have been no deadly encounters,” Eric Hamilton, a lawyer from the Justice Department, argued at one point during the proceedings. “There have actually been fewer deadly encounters because the National Guard has been here.”

Last week, a federal district judge ruled in favor of the attorney general, finding that the deployment was likely illegal and that it violated the city’s rights to self-governance and limits on the president’s authority to assert total control over the local D.C. National Guard, among other issues. Judge Jia M. Cobb’s ruling had temporarily put the deployment on hold though it also had paused it for three weeks, allowing time for the administration to remove the troops, as well as to appeal.

The Guard is a state-based military force, and both state governors and the president have the power to activate its troops under certain circumstances. But when presidents have done so for duty in the United States, it has almost always been at the request of state or local officials.

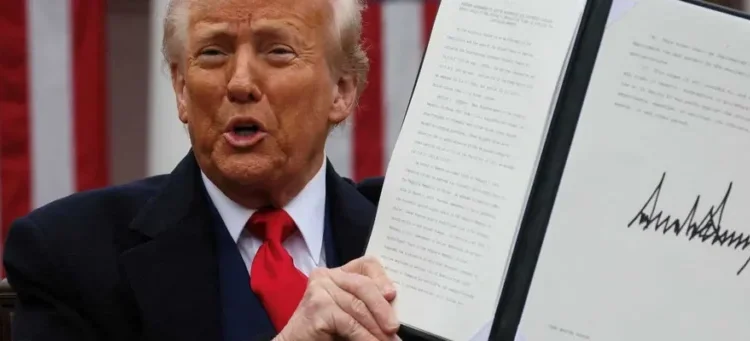

Since June, however, President Trump has moved to send waves of troops to Los Angeles, Washington, Chicago, Memphis and Portland, Ore., saying that military force has been necessary to protect federal buildings and personnel amid protests and to help fight rampant levels of crime — assertions that, with the exception of Memphis, state officials have widely contradicted.

Federal law prohibits the use of the military for local law enforcement, although the District of Columbia, which is not a state, has presented some exceptions. Officials in most of the cities where troops have been sent, which are predominantly Democratic, have said the deployments were unnecessary. Most also have filed lawsuits to block the deployments, with several of them accusing the Trump administration of exceeding its legal authority.

Many Republican leaders have embraced the deployments, saying that they have increased public safety and provided necessary backup for federal agents seeking to enforce ramped-up immigration enforcement policies. In Tennessee, for example, Gov. Bill Lee, a Republican, has welcomed the deployment in Memphis, and local leaders have made a point of working with the extra federal resources, although some have noted that serious crime was already on the decline.

In interviews, some National Guard members have expressed deep ambivalence about the deployments, privately doubting the legality of the missions but publicly reluctant to question the commander in chief.

On Wednesday, as they expressed deep sympathy for the wounded soldiers and their families, some former leaders in the National Guard officials said that troop safety has been an ongoing worry. They pointed out that the assignment itself, which in many cases involved foot patrols in highly visible areas of the nation’s capital, could make troops a tempting target for bad actors.

Brig. Gen. Paul G. Smith, the former assistant adjutant general of Massachusetts whose command included responding to Hurricanes Sandy and Irene and the Boston Marathon bombings, said there are always perils.

“Whenever you put military personnel into any area on a security mission, there is an element of danger, because of what they may represent to people who are struggling with their own demons,” he said.

Campbell Robertson reports for The Times on Delaware, the District of Columbia, Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia.

The post Before the Shooting, Some Troops and Officials Worried About the Guard’s Safety appeared first on New York Times.