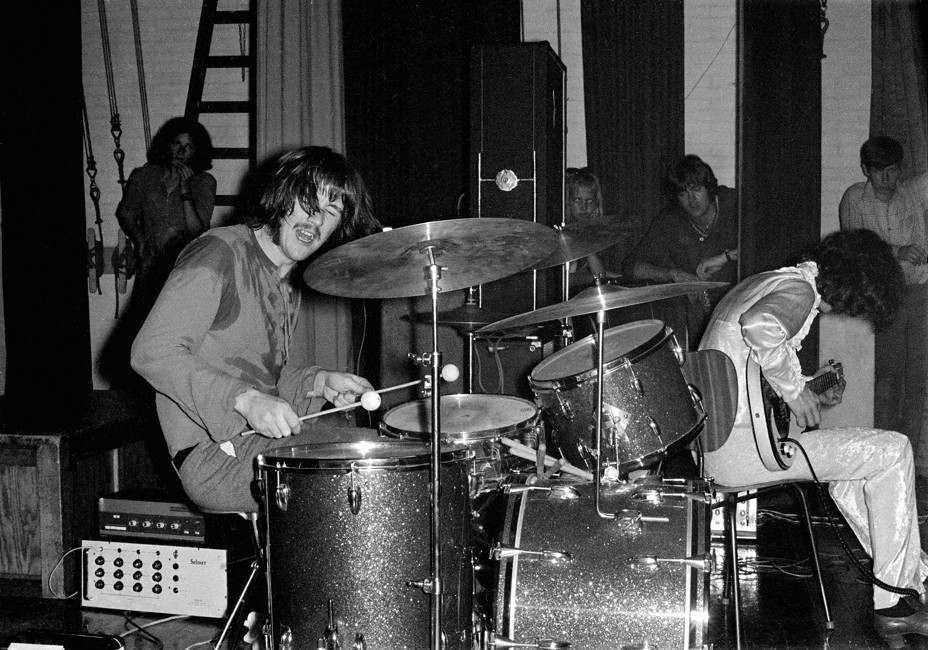

Full disclosure: I play the drums. I play them every chance I get. Although my drumming career has served mainly as a steady education in my own shining mediocrity as a drummer, a reminder that I was put on this Earth for other things, I love hitting the goddamn drums. Left foot on the hi-hat pedal, right foot on the kick-drum pedal, left hand on the snare, right hand on the ride cymbal. When it starts to flow, you’re like da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man: You’re in a holy circle of equilibrium, blissfully distributed, with consciousness diffused to your extremities.

How do you get better as a drummer? Well, you practice: You do the same thing over and over, slowly building muscle fiber while also experiencing, in your brain, the painless, clueless ache of a synapse trying to form. You get better by being in a band, by entering music as part of a volatile, multi-person, multi-addiction organism. And you get better, lastly, via the drummer’s version of the grace of God—which is the jolt, the volt, the heavenly bolt, the electromotive impulse that flashes out from the playing of another, much greater drummer, and claims you.

John Lingan’s superb Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in Fifteen Drummers is full of such moments. Moments of transmission—often via vinyl, occasionally in performance—when the creative spark zips and snaps across the pre-artistic darkness and some young drummer somewhere realizes that he’s going to have to change his life. Dave Lombardo, pre-Slayer, listening in awe to Phil “Philthy Animal” Taylor pummeling through a relentless double-kick-drum pattern on the title track of Motörhead’s Overkill. Jody Stephens, pre–Big Star, in the 17th row at a Led Zeppelin show in Memphis: John Bonham was “like a rocket, everyone else was just holding on.” Tony Thompson, pre-Chic, watching the Mahavishnu Orchestra: “I saw Billy Cobham for the first time—and saw God … It’s still embedded in my soul seeing him play like that.”

The drummer James Osterberg, before he became Iggy Pop, was infatuated with the bluesy playing of Sam Lay. (You can hear Lay’s ghostly snare taps on Howlin’ Wolf’s “Little Red Rooster”; you can also hear him, four years later, tearing through the anarchic-ironic shuffle of Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited.”) Osterberg made a young man’s picaresque pilgrimage from Ann Arbor to Lay’s house in Chicago. “His wife was very surprised that I was looking for him,” he tells Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain in Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk. “She said, ‘Well, he’s not here, but would you like some fried chicken?’ ”

My own little drum crisis/awakening came at the hands (and feet) of Dave Grohl, pre-Nirvana, when I saw him playing with the Washington, D.C., hardcore-punk band Scream. Grohl—skinny, 19 years old—was all attack, all emphasis. He drummed in italics. Simultaneously, there was something subliminal and almost unspeakable about his playing; as devastatingly correct as it was, he also seemed to be pulling information from a rhythmic grid more profound, more capacious, than the mere ticktocking of accurate time.

Because this is the great mystery of drumming: Time. Not just tempo, not just keeping the beat—the guitarist and the bassist can do that—but the drummer’s musical relationship to the flow of Time itself. To the passing of all things, to the universe’s rumble toward infinity. John Bonham’s left foot on the hi-hat pedal—shick–shick–shick—has the cadence of Deep Time. It’s Bonham’s neurological signature: a lilt, an inflection, a swing that microscopically delays or distends the beat while also fulfilling it. Listen to “Whole Lotta Love,” around 1:18, the start of the freak-out section. Listen to that hi-hat going up and down, up and down. Bonham, steady as he is, is not keeping time. He’s releasing it.

His own rumble toward infinity was brief, fiery, and pocked with shadow. Lingan pairs him with the Who’s Keith Moon: “Their drumming was an accurate reflection of each of their personalities—they were loud, they were destructive, they hurt and endangered people, and they both died young and violently from self-abuse.” Here I think I might respectfully disagree. In both cases, the drumming, the art, transcended the personality.

Grohl and Bonham get a chapter each in Backbeats, as does—to my great delight—Earl Hudson from Bad Brains, a low-key powerhouse whose playing steered the shamanic flights of his brother, the band’s front man, H.R., through the ether. The great session man Hal Blaine is also featured, and Clyde Stubblefield from James Brown’s the J.B.’s, the author of the “Funky Drummer” beat that’s since been looped through a thousand hip-hop tracks.

To nondrummers, many of these figures will be obscure. (One main counterexample is Grohl, who made himself a real rock star as the guitarist-vocalist of Foo Fighters.) This is largely the drummer’s fate: to be felt but not seen. And this is the ambition of Lingan’s book—to tell a story of rock-and-roll evolution from the back, from the bowels, from the under-realm of the creator-drummers. How have drummers responded to the increasing power and complexity of the music? How have they themselves increased that power and complexity? By the time we get to Dave Lombardo and Slayer’s Reign in Blood, we are in a zone of Darwinian mutation, as Lombardo pulls off feats of speed and dexterity unimaginable—and probably terrifying—to his drumming forebears.

The sole female among Lingan’s 15 selected drummers is Moe Tucker, of the Velvet Underground. Self-taught, self-willed—“I consciously, purposely, didn’t learn more about drums because I didn’t want to sound like anybody else”—Tucker fused steely minimalism with raw, repetitive impact. If any rock-and-roll drummer could be said to have made their drums drone, it’s her. No crashing cymbals for Moe Tucker: not for her, the big-top vulgarity of those metallic exclamation points. And sometimes no downbeat—the ferocious shuffle she plays on “Run Run Run” is on the snare alone, its clattering, unmoored momentum working like a propellant on Lou Reed’s storytelling. Ka-chunk-a-CHUNK-a-chunk-a-CHUNK … The addicts are fiending around New York City, looking for a fix, a drag, a taste, anything. Maybe this was Tucker’s special compact with Time—Time as narrative; Time as unfolding drama.

And one last thing about Time: Of all the members of the band, it comes for the drummer first. Guitars get heavier as you get older, high notes harder to hit, but the drummer pays a private tax to mortality. The drummer’s strength goes faster. Exactly how fast depends, to a degree, on the music. Metal drumming is famously punishing, and high-speed punk rock, as Lingan writes, “has always survived on heroic drumming. Someone has to sustain that pulse.” But even the mid-tempo drummer will have their moments of naked endurance. A 2008 study of Blondie’s Clem Burke revealed that, during live sets, he played with the stamina of an athlete, burning about 600 calories over the course of an 82-minute show. Many bands, when they re-form for their 20th- or 30th-anniversary tours, have a new man, younger and stronger, on drums.

[From the November 2015 issue: James Parker on the twilight of the headbangers]

So what’s a jowly old superannuated drummer to do? How do you stay on that drum stool and keep playing that funky/punky/heavy/wicky-wacky whatever-it-is? Well, you stop thrashing. You move more precisely; you breathe more deeply; you manage your force more shrewdly. You measure the dosage of power in every stroke. You use, in a word, technique. It’s like life.

* Lead-image source: Kevin Nixon / Classic Rock Magazine / Future Publishing / Getty

This article appears in the January 2026 print edition with the headline “Respect the Drummer.”

The post Respect the Drummer appeared first on The Atlantic.