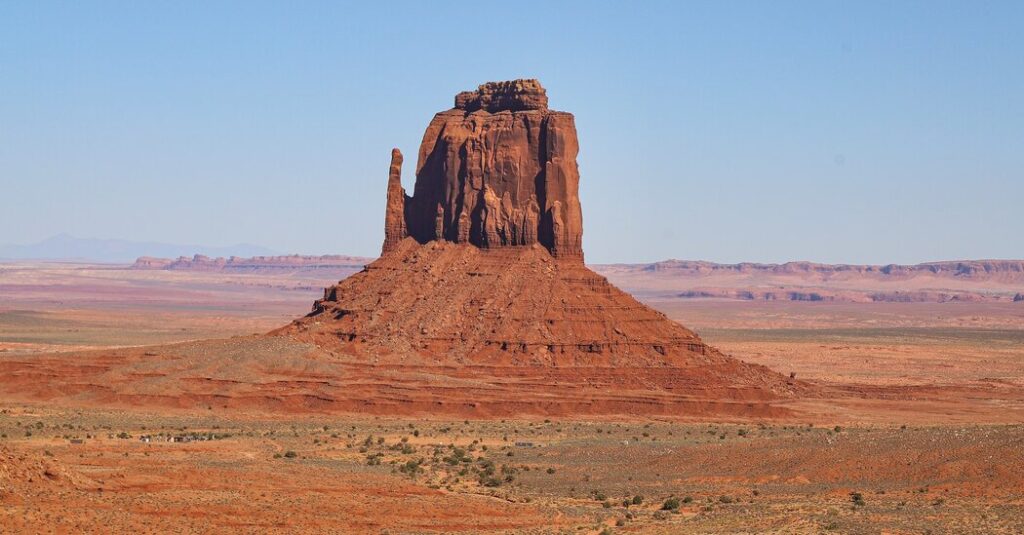

The red sandstone buttes and rugged expanses of Monument Valley, in the Navajo Nation, have long invited visitors from around the world to experience this landscape worthy of a classic western film.

But the pandemic hit the region’s tourism industry especially hard. Parks in the Navajo Nation — which stretches across Arizona, New Mexico and Utah — didn’t fully reopen until 2023. And locals like Charlene Johnson, the owner of Dineh Bekeyah Tours, a company that guides visitors through Monument Valley, waited what felt like an eternity for tourists to come back.

Last year, it seemed as if that moment had arrived. Business was starting to boom and, with the cost of gas and vehicle maintenance spiking, Ms. Johnson made plans to raise her prices.

Then, early this year, demand began to plummet. By summer, tours that were once full of visitors from places like Canada, Italy and South Korea were heading half-empty into Monument Valley, one of the most visited parts of the Navajo Nation.

Raising prices didn’t seem like such a good idea anymore. So for the first time since she founded the company 11 years ago, Ms. Johnson did the opposite: She lowered prices on some of her most popular tours, hoping to keep them fully booked.

“It’s like you’re stuck in the middle,” Ms. Johnson, 65, said in an interview last month. “What do I do? If I raise my price, will people still buy it?”

Fallout from the slump in travel to the United States has reached all the way to Monument Valley, where a dozen Navajo guides told The New York Times that their international business evaporated this year. Foreign arrivals to the United States overall are down nearly 5 percent, or 2.3 million people, through August compared with the same period in 2024, according to the U.S. Travel Association.

That decline has had a major effect on popular Navajo Nation destinations like Monument Valley and Antelope Canyon, about two hours to the west. In the valley, where tour guides estimate as many as three in four visitors come from abroad, nearly 525,000 tourists arrived in 2024, according to the Navajo Nation Parks and Recreation Department, which runs that park and four others. About 320,000 visited this year through August, the end of peak tourist season and the last month with available data.

The Navajo parks are not as well known among travelers as those in the U.S. national park system, which boomed after the pandemic — at least until this year’s staffing and budget cuts — while Navajo parks have struggled to make up lost ground.

Still, tourism supports thousands of jobs and is a main economic engine in the Navajo Nation, where the estimated median household income is around $30,000 per year, according to an analysis of U.S. census data. It was $83,730 nationally in 2024.

“It’s hard to make ends meet even when the guiding is good,” said Helen Myerson, 62, a tour guide for Goulding’s Monument Valley, a major hotel and tour operator. “If the guests stop coming, especially the international guests, we’re all going to be in real, real trouble.”

Guides Feel the Pinch

Monument Valley is sacred ground for the Navajo, or Diné, as members of the tribe call themselves. As with many places across the Navajo Nation, visitors need a Native guide to visit most sites off the major highways, a requirement meant to encourage engagement with the tribe’s culture and history.

On a tour of Monument Valley one evening in October, Ms. Myerson pointed out mesas said to represent beans, mittens, a bear and a rabbit. She thanked guests for spending their time and money to bounce around in the back of a truck learning about the traditions of the Diné, which means “the people.” Each guest’s presence, she told the group, helped her support herself and her family.

“A lot of jobs are scarce around here,” she said.

Increasingly, the guides are struggling. Cory Begay, a guide with Three Sister Navajo Guided Tours, said she often led three tours a day before the pandemic. Now, she said, most days it’s one or none.

Across the Navajo Nation, the stories are the same. And even where tour companies report doing well, cracks are emerging.

Lake Powell Navajo Tribal Park, which includes the photogenic sandstone crevices of Antelope Canyon, welcomed more than 1.2 million tourists in 2024, a postpandemic record. But the number of visitors to the park this year through August fell 13.5 percent compared with the same period last year, according to the tribal parks department.

Canadians Look Elsewhere

San Juan County, Utah, which includes the Navajo Nation’s northern reaches, offers some clues as to what’s happening.

Data from the credit card company Visa showed spending by Canadians, who make up the county’s largest share of international visitors, was down 37 percent this year through June compared with the same period last year, said Allison Yamamoto-Sparks, the county’s visitor services manager.

The downturn in Canadians “makes the difference from having a good year to having to scrape through,” said Jennifer Davila, who owns La Posada Pintada, a boutique hotel in Bluff, a town in San Juan County near the Navajo Nation border. Ms. Davila said about 75 percent of her guests — and nearly all her international guests — come specifically for Monument Valley. Reservations at the hotel were down more than 15 percent this year, she said.

Steve Simpson, who owns Twin Rocks Trading Post and Cafe in Bluff, worried that next year could look even worse, since international tourists often book their trips far in advance.

“My fear is not so much this year, which we have managed to muddle through,” Mr. Simpson said. “My fear is what happens next year, when people are booking their travel now and saying, ‘Well, we’re just not going to go to America.’”

Bobby Martin, the Navajo Tourism Department’s manager, said that in recent months he had spoken with Canadian tourists who told him they would avoid the United States because of President Trump’s tariffs and musings about annexing Canada. Canadian travel to the United States declined in October for the 10th consecutive month.

In addition, Asian and European tourists tend to spend more money than Americans do, said Shaunya Manus, a marketing specialist for the tribal tourism department, meaning that losing them could have an outsize effect on the Navajo economy.

“They can come in and buy a $2,000 rug like it’s nothing,” she said. “If the international market dissipates, it’s going to hit us really hard because a lot of people need those sales to make their income.”

A Boost From Cash and Tech

Chris and Jackie Redman, a couple from the south of England, visited the Navajo Nation and nearby national parks in October and said that learning about the tribe, with Ms. Myerson as their guide, was a highlight.

“It’s utterly phenomenal here,” said Mr. Redman, 70, as the moon rose over Monument Valley’s Mitten Buttes. “You can’t take a bad picture.”

Tourism officials hope they can spread the word of visitors’ positive experiences to draw in new guests. The tourism department, which is generally funded by hotel occupancy taxes, had its budget drop to near zero during the pandemic, kneecapping its advertising operation in the years since.

A new pot of cash offers a promising start. Navajo officials granted the tourism department roughly triple its normal budget for fiscal year 2026, bringing it to “several million dollars” for the first time since the pandemic, Mr. Martin said. He hoped the funds would reinvigorate the department’s staff, which has declined to six people from about a dozen in the early 2000s. The Navajo parks and tourism departments don’t receive any direct funding from the U.S. government.

Up first: hiring Placer.ai, an Israeli technology company that uses cellphone location data to understand visitor behavior and trends.

“Those numbers will really be beneficial, not only to us, but to tour operators and for future marketing and advertising,” Mr. Martin said. “It’ll help us with what locations to target. It’ll help with our budget pitch for next year. It’ll help us write grants.”

There are just eight hotels in the entire Navajo Nation, which at 27,000 square miles is larger than West Virginia. Many visitors stay in border towns like Bluff and Page, Ariz., where their dollars don’t directly support the Navajo economy.

But visitors will soon have more places to stay within the nation’s borders.

A 75-room hotel in Shiprock, N.M., is expected to open next summer. (Another hotel, in Shonto, Ariz., was built last year but had yet to open because of a dispute over a lease agreement, officials said.) The tourism department is also spearheading development of a sort of Navajo-run Airbnb platform, allowing tribal members to turn their homes into vacation rentals.

And in late 2023 the Navajo Nation purchased Goulding’s, the Monument Valley tour and hotel giant, for nearly $60 million from its previous non-Navajo owners, ensuring that income from tourism to the area stays within the nation’s borders.

But such efforts come with anxiety, too. David Holliday, a co-owner of Monument Valley Rain God Mesa Tours, said he feared that giving big businesses more inroads into the tourism sector would squeeze out companies like his, which has just a handful of part-time guides and no website — just a tent outside the park’s visitor center.

“It’s the only income we have now,” said Mr. Holliday, 66. “We don’t want people from outside coming in and messing things up.”

Navajo tourism officials acknowledge that federal policies on issues like tariffs and immigration are complicating their efforts to draw foreign tourists. But with a brand built on emphasizing their distinct cultural identity, they see opportunities.

“Politically, the environment is really hostile,” Ms. Manus said. “But I don’t want international people thinking that’s how all of the United States is right now. Our region is more than happy to host a lot of international travelers.”

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2025.

Gabe Castro-Root is a travel reporter and a member of the 2025-26 Times Fellowship class, a program for journalists early in their careers.

The post Soaring Red Rocks, Perfect Blue Skies and Half-Empty Tours appeared first on New York Times.