The first sign of trouble arrived by text. On Dec. 17 of last year, at 2:33 p.m., my younger sister, Melissa, pinged me from Houston to say that our 78-year-old father had veered off course while driving himself to a medical appointment.

“He has missed his exit,” she wrote. “I don’t want to call him and tell him because he will be pissed that I am tracking him. What do we do?”

“Honestly just let him run,” I wrote back from my home in Washington.

This was not the first time Dad had gone rogue while driving. Just the day before, he had cruised in aimless circles around unfamiliar neighborhoods for over an hour, dismissing worried calls from our mother. But this time he was missing lab appointments related to his bladder cancer.

The family knew that Dad was chafing under the restrictions that went with his chemotherapy. No crowds! No gardening! No letting the dog lick his face! But we also knew the drugs could cause cognitive issues. Dad’s oncologist had warned us to be on alert for odd behavior. Like an overprotective mom, my sister had started tracking his phone, mostly without his knowledge. My father got crabby when he thought anyone was treating him “like an invalid.”

“Maybe he is just trying to explore every major Houston freeway this week?” joked Melissa, whom we all call Mel.

“Everyone needs a hobby,” I suggested.

Judge if you must. Dark humor is my family’s coping mechanism of choice.

The hospital called our mother to ask why my father hadn’t shown up, alerting her to the situation. Mom called Dad, who claimed to be stuck in traffic — true only if “stuck in traffic” meant driving in circles.

As hour two of our vigil approached, I suggested my sister take a break.

“I can’t,” she said. “It’s like the third season of ‘Stranger Things.’ I don’t want to watch but I couldn’t look away. I have to know what happens.”

Dad eventually drifted home — after burning up 49 miles over the course of nearly two hours and missing two appointments. He tried to shrug off the whole episode, but something was clearly off. Mel and I agreed that I should at least talk with him about hitting the pause button on driving. (Spoiler: That did not go well.)

We had no idea what was coming.

Caring for an aging loved one is a journey — and not a low-key pleasure trip with a clear itinerary you can plan and pack for. The road is constantly dipping and turning to accommodate the vagaries of aging. I, for instance, have lost count of how many bones my mother has broken in recent years.

Rolling through his 70s, my father, Bill, a Navy veteran and a retired nuclear energy executive, was a force of nature: active, social, independent. Until he wasn’t. In August 2024, he was diagnosed with bladder cancer. And just like that, my sister and I were scrambling to address his proliferating health needs, as well as to assume his role supporting our medically fragile mother, Brenda.

The latter was what worried Dad. Facing months of chemotherapy followed by surgery, he never expressed anxiety about his prognosis. He did share his fear of being unable to take care of Mom. I assured him that Mel and I could handle whatever lay ahead.

You can see where this is going. Faster than you can say “chemo brain,” my family’s caregiving experience spiraled into a chaotic spectacle that was part harrowing medical drama, part sitcom. Even early on, there were 2 a.m. phone calls, mangled medical equipment, emergency room visits, dizzying medication schedules and epic clashes over how much meddling Dad would stomach from his two daughters. “You are your mother’s child,” he groused whenever he felt I was being bossy. (Which, to be fair, I often was.) Our chat about him relinquishing the car keys featured an impressive amount of profanity, on both sides. It was, I think, the only time I ever raised my voice to my father.

And all that was before my mother fell and shattered her leg during one of Dad’s hospital stays. This landed her at a different hospital across town. Awaiting surgery. As a freak snowstorm was bearing down on Houston.

But even in our most frenzied moments — as when Mel and I were pinballing between hospitals, trying to keep one parent from freaking out about the other — we knew we had an easy lift compared with many other families. We had both the financial resources and a support system of family and friends to smooth out big bumps. We had each other. (Never have I been so grateful not to be an only child.) Plus, my parents had taken steps to ease the transition to their golden years; they had signed advanced directives and moved into a senior living community that offered continuing care. They had, God love them, covered as many bases as they could.

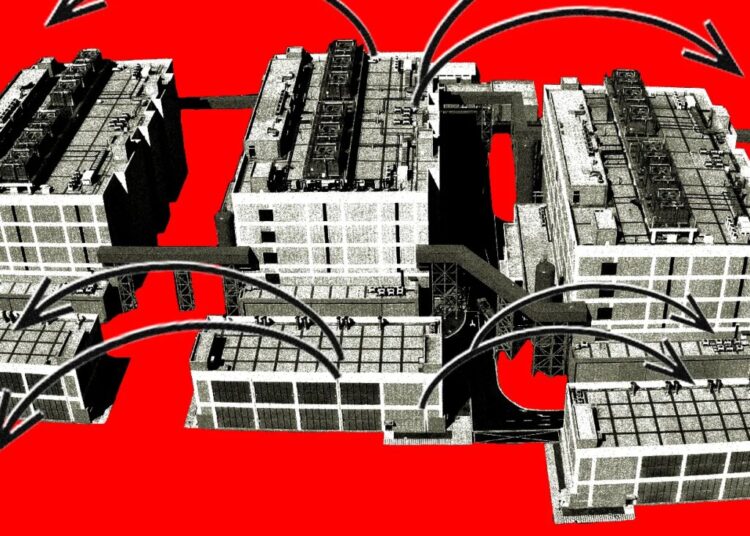

The same cannot be said of America writ large. In recent years, I have become borderline obsessed with the graying of the nation and the challenges it brings — challenges for which our society has not prepared. The numbers are ominous: Each day, more than 10,000 baby boomers turn 65. Between 2010 and 2020, the population of seniors grew nearly five times faster than the overall population. That is sending the demand for medical care, long-term care, safe housing and other resources skyrocketing, along with the costs.

On the front lines of this transformation stand nonprofessional family caregivers. An estimated 59 million people in the United States are providing informal care for an adult, the overwhelming majority looking after someone age 65 or older. A small percentage of family caregivers receive payment for their work, but the vast majority do not. The need crosses nearly all demographic lines: age, race, geography, politics, religion. In our fragmented society, it is as close to a universal concern as you can find.

Beyond the numbers are the politics. While caring for loved ones is a deeply personal charge, the weight of that responsibility is influenced by public policy in areas ranging from taxes to labor law to entitlement spending. In his 2024 campaign, Donald Trump promised a tax credit for family caregivers. “They add so much to our country and are never spoken of, ever, ever, ever, but they’re going to be spoken of now,” he vowed during his rally at Madison Square Garden the week before Election Day.

Back in office, however, Mr. Trump promptly abandoned the idea. It was not among the raft of tax cuts in his domestic policy bill. Worse still, he has taken steps likely to make families’ caregiving burdens far heavier. Two major moves stand out. One is the slashing of Medicaid. The other is the broad-based assault on immigration. Together, those actions risk upending a caregiving ecosystem already under strain, throwing millions of families into crisis.

The week after my father’s joyriding, things took a dark turn. On Christmas Day, Dad became convinced — wrongly — that the nephrostomy tube placed to drain his right kidney had malfunctioned. So, like any good ex-engineer, he “fixed” it. That is, he mangled it so that it was in fact not draining properly, then hid his handiwork from the rest of the family until close to midnight.

It took much cajoling by my brother-in-law, Jason, to get Dad to the E.R. the next morning. Once they were there, the tube became the least of our worries. My father’s hemoglobin was dangerously low. The doctor pressed to admit him. Dad was more interested in hectoring every medical professional he saw about how his nephrostomy drain needed a “filtration system” to prevent “backflow.” This was, to put it gently, crazy talk — and further convinced everyone he should be admitted ASAP.

Mel promptly renamed the family text chain “Backflow.”

Most people get that caregiving is stressful. But no one warns you how farcical it can be. When your grandma refuses to wear her hearing aids, then hollers unflattering commentary about everyone she passes. When your dad keeps trying to bribe the orderlies at the cancer hospital to wheel him outside for a smoke break. When your mom becomes convinced your husband and your best friend are having an affair and are plotting to steal all her furniture. (True stories.) These are the moments that don’t make it into the family’s annual holiday letter.

Caring for seniors, while a labor of love, can nonetheless be grinding. It is often compared to parenting, but the emotional and cultural space it occupies is very different. With a frail parent, there is no sense of guiding someone toward a bright future. Quite the opposite. There is no senior equivalent of mommy-time playgroups, much less an ocean of lighthearted books, movies and social media posts chronicling the experience. A diaper disaster involving your toddler makes a great party story. One involving your mother? Not so much.

Feelings of isolation and loneliness are common among family caregivers. Nearly one in four say they feel alone, according to a report by AARP. Many talk about “feeling invisible,” said Margie Omero, who has conducted focus groups for AARP. Many caregivers don’t talk a lot about their experiences, she said, while many noncaregivers “dismiss the work that goes into it until they have to do it.” (Ms. Omero helps run political focus groups for Times Opinion.)

I see this all the time. Those not in the caregiving trenches often don’t want to think about the issue, period, much less chat about it. I mean, who wants to dwell on frailty and death? Among those in the thick of it, many need a nudge to open up — as though broaching the subject themselves would be bad form — but then their stories pour out.

Surveys and other research spotlight the toll this duty can take. Sixty-four percent of family caregivers experience high emotional stress, and 45 percent suffer physical strain. Between 40 percent and 70 percent show clinically significant symptoms of depression. Caregivers report chronic conditions — including heart disease, cancer, diabetes and arthritis — at almost twice the rate of noncaregivers (45 percent vs. 24 percent). Women are particularly hard hit, reporting higher levels of stress than men.

The more involved the caregiving, the greater the strain. More than half of family caregivers handle medical or nursing tasks in addition to helping with the activities of daily living. Looking after someone with dementia can be extra rough. Loved ones’ confusion, fear and often resentment and anger about what is happening make taking care of them all the more complicated. And all too often, a physical issue will contribute to cognitive troubles — or vice versa — resulting in a snarl of mutually reinforcing problems.

Even the most devoted family caregivers may occasionally need outside help, if only a few hours of respite care a week. When that happens, many wind up relying on America’s newcomers. Foreign-born workers are the lifeblood of paid caregiving in the United States. More than 820,000 immigrants provide long-term care services in the direct-care work force (defined as including aides and nurses), according to KFF. Overrepresented in their fields, foreign-born workers account for 28 percent of personal care workers and 40 percent of home health aides, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

High demand for such workers is already causing shortages in home-based and institutional care alike, with the situation on track to get worse. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that the demand for care aides will rise 17 percent over the next decade, making it one of the occupations with the most growth.

As Mr. Trump throttles the flow of immigrants into the United States, families are likely to have more and more difficulty finding help. Already, the cancellation of the temporary protected status of hundreds of thousands of migrants is causing upheaval. “We’re seeing a jarring, sudden loss of workers, of people who are being sent back” to their home countries, said Katie Smith Sloan, the head of LeadingAge, an association of community-based organizations that provide services for seniors. In addition to creating gaps in staffing, “the relationships that they’ve built with the residents and clients that they’re serving are just broken,” she said.

Further disruptions loom. For instance, the administration has put new barriers on a type of visa that “brought in a lot of nurses from the Philippines,” said Ms. Smith Sloan. Facing access barriers and a hostile climate in the United States, those nurses are likely to head for more welcoming countries, such as Canada, Germany and Australia, she said. “The more restrictive we are, the more it’s going to hurt us in the long run.”

In late January 2025, my father was released from the hospital frailer and more disoriented than ever. His oncologist suspected he was suffering from hospital delirium, compounded by a scorching urinary tract infection. (Fans of “Succession” may recall the cognitive dangers of severe U.T.I.s.)

Worse, Dad was coming home to an empty apartment. My mother, after surgery to repair her leg, had been transferred to the post-acute-care center in their community. But even absent a fall, she could not have looked after Dad. He was now a serious fall risk who needed eyes on him around the clock. Until he rallied, the situation was more than the family could handle.

Mel and I arranged for coverage by a parade of home-health aides from a Houston-based agency called Family Tree. Dad was less than thrilled. He disliked being fussed over and periodically ordered the aides to leave him alone — or even leave altogether. Plus, he missed my mother. His agitated, often salty calls to family members surged. We began comparing notes each evening to see who had received the most. My brother-in-law always won. Dad would ring Jason two dozen or more times a day.

The Family Tree aides were endlessly patient. Mostly women, hailing from a variety of countries, they would beg, boss and jolly my father into getting up and dressed and moving through his day — and at night, dissuade him from going out for a walk at 2 a.m. Dad’s favorite aide was the lone man in the bunch, Shabani Ibrahim, who had come to the States from Tanzania in 2009. In addition to working with Family Tree, Shabani works with individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in group homes. He told me how much he loves to “help others who need assistance and care.”

Caregiving professionals observe that foreign-born workers in particular tend to see looking after seniors as desirable, meaningful work. Many come from cultures that revere their elders, noted Daniel Gottschalk, the chief executive of Family Tree, which relies heavily on foreign-born workers. For anxious families seeking help with Mom or Dad, this is a tremendous comfort. But it’s a benefit that Mr. Trump’s anti-immigration crusade is undermining. “When you lose the people who think that this is a great job, it just makes it much tougher, and what you’re left with are the people who think this is just a job,” Mr. Gottschalk said. “Then it’s transactional, and you lose all that soft touch.”

This “soft touch” proved invaluable, and incalculably reassuring, during my father’s illness. Shabani could persuade Dad to eat when no one else could. He rubbed cream into Dad’s paper-dry skin to prevent infection. He made Dad laugh. And he did not bat an eye as my father increasingly mistook him for an old co-worker or family member. Which was lucky, because it turned out Dad wasn’t suffering from short-term delirium. He had Alzheimer’s, diagnosed in February when the oncologist sent him for a neurological assessment to determine when chemo could resume. Once again, the road shifted beneath us.

At this point we should address the 800-pound caregiving gorilla in the room: money. As challenging as caregiving can be for anyone, families with limited financial resources face next-level stress. Even for families not employing professional aides, the costs quickly pile up. Family caregivers spend on average over a quarter of their annual income on caregiving, factoring in housing and medical costs. On top of such direct expenses, add the cost of taking time away from their paying jobs to handle caregiving duties like running errands, taking loved ones to the doctor and so on.

With my mother in a rehab facility and Dad receiving 24-7 care, the bills started rolling in. And they stung. Mom’s expenses were largely covered by Medicare — until she stayed beyond what the program allowed. The cost of Dad’s aides, around $3,500 a week, was out of pocket from the get-go, since neither Medicare nor private health insurance typically covers most long-term care costs.

My father had saved enough money to ensure that the costs of his and Mom’s care would not fall on their children. Many are not so fortunate. For them, the bulk of such costs falls to Medicaid, which is by far the nation’s largest payer for long-term care. The program covers 61 percent of the $415 billion spent annually on such care. In many cases, even seniors who start out with a nest egg need to do what is called a “Medicaid spend down” of their assets or income to qualify for the program. That is, they need to make themselves poorer to get their long-term care covered.

Nearly two-thirds of America’s nursing home residents have Medicaid as their primary provider of coverage, and roughly one in five assisted living residents rely on it to pay for daily services. It also helps pay for the goods and services that make it possible for many seniors to age at home, from wheelchair ramps to shower grab bars to adult diapers.

I say “helps pay” because, depending on where you live, Medicaid may cover only part of your costs. And again, demand often outstrips supply. As of 2024, 167,000 “seniors/adults with physical disabilities” were waiting for home- and community-based care assistance, according to KFF. (The total number of people waiting on home care, including those with intellectual disabilities, was over 700,000.) In a 2023 survey, 49 states and the District of Columbia reported a shortage of workers providing home- and community-based care. Florida did not respond.

Mr. Trump’s domestic policy law could make things so much worse. The law is projected to reduce federal Medicaid funding by over $900 billion over the next decade. As these reductions start to bite, states will need to make tough decisions about what, and whom, to stop covering. The idea that caregiving access will not take a hit seems either naïve or intentionally obtuse — especially for seniors hoping to age at home.

“What we know from history is that when cuts are made by states, they hit home- and community-based services first,” said Ms. Smith Sloan. Unlike nursing home coverage, she said, home-based care and services are “not a mandatory benefit under federal Medicaid laws, so they are an easy target for states when they have to find savings.”

Worse, many family caregivers themselves are on Medicaid and will be subject to the new work requirements put in place by Mr. Trump’s domestic policy law. Caregivers looking after young children or loved ones with disabilities are exempt, but those looking after seniors were not granted a specific exemption.

As the doctors explained it, my father likely had been masking symptoms of Alzheimer’s for years. When the cancer and chemo and attendant infections overloaded his system, the dementia was unmasked — and progressed with breathtaking speed.

Rampaging Alzheimer’s meant my father was no longer a good candidate for surgery or additional chemotherapy. More personally, Alzheimer’s ran in his family and had long been his greatest fear. Mel and I knew he would not want to endure debilitating treatments to keep his body functioning while his brain betrayed him. We knew it. But we still had to break his diagnosis to him and ask what he wanted to do next.

Long ago, my sister and I adopted a rough division of labor when dealing with our parents: Since she lives near them and handles the daily challenges, I get called in to take the lead on hard talks. My parents basically knew this. “Don’t make me fly down there,” had been my joking threat for years whenever Mel or I feared they weren’t taking care of themselves.

Telling your father his worst fear has come to pass is a different level of hard. Mel and I went to see him on a sunny morning in mid-February. (Mornings were his clearest time.) He was tucked into his favorite chair, and I moved over a footstool to sit close. When I told him the dementia diagnosis — Mel and I agreed that avoiding the term “Alzheimer’s” was best — he flinched and uttered a quiet “Oh.” Or maybe it was “OK.” He didn’t say much for the rest of the conversation. But when it came to his wishes going forward, there were no surprises. He wanted comfort care. Nothing more.

A few weeks later, an infection prompted us to start him in hospice care. By then, he had come unmoored in time and would tell visitors he was playing poker with his brothers, both deceased. The last person he consistently recognized was my mother. He died on April 23.

Mom has insisted on continuing to live in their apartment by herself, with frequent check-ins from Mel and liberal use of grocery delivery services. We have all committed to a flexible, one-day-at-a-time approach to the arrangement.

My family’s caregiving experience with my father was intense but relatively brief, a matter of months rather than years. I emerged even more concerned about the nation’s caregiving crisis — the shortages, the expense, the shaky support systems, the lack of thoughtful attention, much less urgency, from policymakers.

America is aging. Fast. We need leaders who understand the scope of the challenge and take it seriously. Despite his campaign happy talk about valuing family caregivers, Mr. Trump clearly does not. He has given them not so much a helping hand as a punch in the face, plowing ahead with policy moves that threaten existing support systems. He owes his voters — all voters — better.

While Mr. Trump may not have to worry about who will take care of him and his family as age takes its toll, few of us have that luxury. Time and chance eventually come for us all — and most families will wind up needing at least a little help navigating the journey.

Source photograph courtesy of the Cottle family.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post ‘We Had No Idea What Was Coming’: Caring for My Aging Father