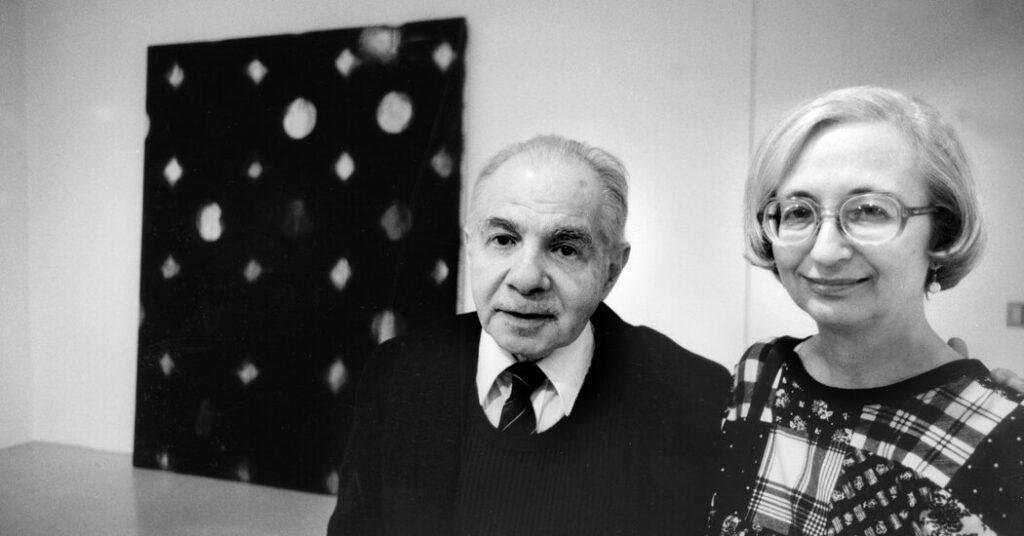

Dorothy Vogel, a librarian who, with her postal-clerk husband, Herbert, bought thousands of works from future art stars like Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd, stashing them in their cramped one-bedroom New York apartment and eventually handing over the entire collection to the National Gallery of Art without ever turning a profit, died on Nov. 10 in Manhattan. She was 90.

Her death, in a hospital, was confirmed by Kathryn Obler, a cousin. Ms. Vogel left no immediate survivors.

That the Vogels, who were modest in dress and bearing, would come to take their place as benefactors alongside Rockefellers and Mellons was every bit as unlikely as it was that some of the works they collected — like the tiny snippet of frayed rope by the Post-Minimalist artist Richard Tuttle — would land in one of the world’s premier art museums, alongside Vermeers and Van Goghs.

Throughout their decades as collectors, Ms. Vogel worked at the Brooklyn Public Library as a reference librarian, and Mr. Vogel, a high school dropout from Harlem, did the night shift at a post office sorting mail. Their formal training in art, such as it was, consisted of the art classes Mr. Vogel took at New York University as a young man and a few painting lessons the couple took together.

Their rent-controlled apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side functioned as a fine-art storage locker as well as an exhibition space. Stacked on the floor and crammed into closets were some 4,000 works by luminaries like the Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein; the photographers Cindy Sherman and Lorna Simpson; the German sculptor and performance artist Joseph Beuys; the Minimalist Robert Mangold; and the video art pioneer Nam June Paik.

The couple did have their limits, however. Contrary to art-world legend, “we never kept art in our oven,” Ms. Vogel said in a 1992 interview with The New York Times. “We didn’t set out to live bizarrely.”

While works by the artists the Vogels favored often sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars, or even millions, their collection was quite literally priceless, in the sense that none of it ever went to market. “I didn’t make a $20 bill outright on any artist,” Herbert Vogel, who died in 2012, told “60 Minutes” in 1995.

Ms. Vogel added, “In the 1980s, there was a big explosion in the art market, where the prices went very high — unrealistically. Then all of a sudden, it dropped. But we were not part of that. We didn’t sell.”

Instead, in 1992, the Vogels began donating their vast holdings to the National Gallery in Washington in return for a small annual stipend — a tiny fraction of the collection’s value.

“We like the idea of giving it to the nation,” Ms. Vogel said in 1995. They also liked the idea that the museum “was free, it didn’t charge admission,” she added, and that “once you give them something, they will not sell it.”

In 2008, the couple partnered with the National Gallery to donate 50 works to a museum or gallery in each of the 50 states, an endeavor chronicled in the 2013 documentary film “Herb & Dorothy 50×50,” Megumi Sasaki’s follow-up to her 2009 film about the couple, “Herb & Dorothy.”

If the Vogels did not make any money off their collection, they did not spend much on it, either. With civil-service incomes, the Vogels lived frugally, didn’t own a car and often ate TV dinners. As for art, they bought what they could afford — usually at a discount, from underground artists — and sometimes received it free of charge.

In the early 1960s, “Pop Art was already too expensive, and so was Abstract Expressionism,” Ms. Vogel said in “Herb & Dorothy.” “So if you wanted to buy art, the only thing we could afford would be the Minimal. And we had no competitors.”

Back then, conceptual art was so new that the couple couldn’t tell “how good it was or bad it was,” Mr. Vogel said. The Photorealist painter Chuck Close was more certain, saying of them in the documentary, “They like the most unlikable art.”

Years later, many people were still baffled. In the “60 Minutes” segment, the reporter Mike Wallace toured their apartment with a quizzical expression, pausing in disbelief when he saw a three-inch stretch of ordinary white rope nailed to the wall next to the front door — a 1974 original by Mr. Tuttle called “3rd Rope Piece.” (It’s now housed at the National Gallery.)

“That’s a work of art?” Mr. Wallace asked, both a question and a jab.

In a 2013 interview with HuffPost, Ms. Vogel allowed that Mr. Tuttle’s “work is difficult, and people have to see it a few times to get into it.”

She added: “A lot of the work from the collection is like that: At first glance, it’s hard, but you see it again and again and again, and it grows on you.”

Dorothy Faye Hoffman was born on May 14, 1935, in Elmira, N.Y., the younger of two children of Edward Hoffman, who sold paper goods and novelties, and Anna (Kantrowitz) Hoffman.

After graduating from Elmira Free Academy, she enrolled at the University at Buffalo and later at Syracuse University, where she received a bachelor’s degree in library science. She went on to earn a master’s degree in the same subject from the University of Denver.

Seeking culture and adventure, she moved to New York with a friend in about 1958. Three years later, she met her future husband, already an eager art enthusiast. The couple married in 1962 and began dabbling in art, starting with painting classes to test their skills.

“One day, we looked up and realized that the other artists were better than we were,” Ms. Vogel said in a 2017 interview with the Establishing Shot blog, published by Indiana University, “and that we were better at collecting than painting.”

Mr. Vogel began stopping in at the Cedar Bar (later Tavern) in Greenwich Village, an artists’ haunt, where he listened to Abstract Expressionists like Mark Rothko and Franz Kline expound on their theories. Before long, the couple were scouting around for up-and-coming artists who were venturing even further into unexplored territory.

By the early 1970s, the Vogels had become a known quantity on New York’s avant-garde scene, although some artists did not quite understand their methods — or means.

In 1971, for example, the couple agreed to spend three months cat-sitting for the Bulgarian-born artist Christo, who was becoming famous for his monumental works of environmental art, and his wife and collaborator Jeanne-Claude. In exchange, the artists gave them a framed prototype collage of the project Christo was then working on, “Valley Curtain,” a vast stretch of orange nylon that walled off the Rifle Gap in Colorado like a dam.

That was not the deal the artists had hoped for at the outset; they originally assumed that the Vogels were wealthy collectors. When the Vogels first contacted them, Jeanne-Claude took the phone call, she recounted in “Herb & Dorothy”: “I put my hand on the phone and said, ‘Christo, it’s the Vogels. We’re going to pay the rent.’”

“They didn’t know,” Ms. Vogel responded, “that we could barely pay the rent ourselves.”

Alex Williams is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk.

The post Dorothy Vogel, Librarian With a Vast Art Collection, Dies at 90 appeared first on New York Times.