“What is country music even, do you think?”

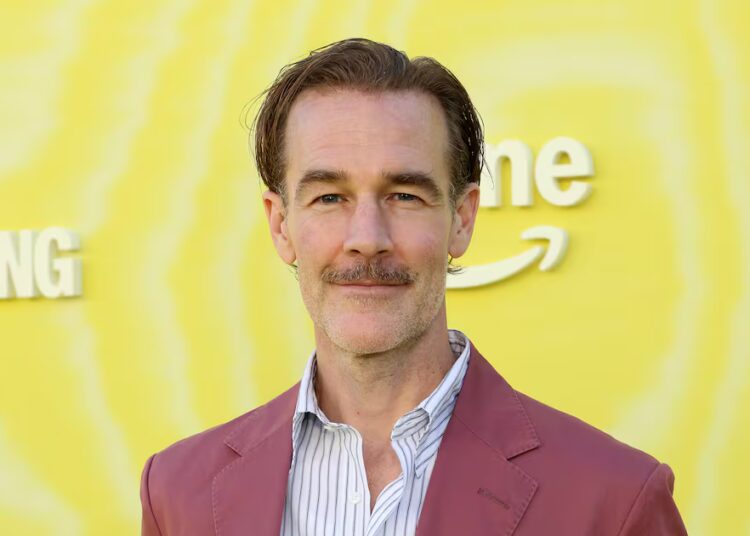

Shaboozey, the most striking new country star of the past few years, asked me this question last fall. We were standing outside the Cincinnati hotel where he was passing some rare days off from touring, binge-watching “The Fall of the House of Usher” with a visiting friend.

“Most music doesn’t translate, in any genre, unless there’s some sort of truth and authenticity,” he said, lighting a cigarette. “When I started making music about the things that interest me in life, the things that I found valuable in my experiences, and I wrote from that perspective, with a guitar behind it, singing in my voice — it’s now country music, I guess.” He laughed and shrugged.

Shaboozey moves through the world with the polite confidence of a good-looking former athlete with nice parents — he is 6-foot-4 and was, in fact, a high school linebacker — but that low-key swagger comes with a restless artist’s brain. “This art thing is not very objective,” he told me. I asked if he found that appealing, and he nodded vigorously. “It’s the essence of why I stopped playing sports,” he said. “Sports is very objective. How many yards did you throw? What is your quarterback rating? Music is like, somebody right here” — he gestured to the semi-empty streets — “could be making a song that will be No. 1 for 50 weeks. It could happen, if they just recognize the patterns and follow their inner voice.” He paused and exhaled a plume of smoke. “I think being in my purpose, and finding whatever that authentic voice is for me, got me here. There’s no other way.”

I first met Shaboozey earlier that fall in Washington, D.C., when his own single, “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” was around its 10th week at No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100. Backstage before a show at the 9:30 Club, he was holding court with friends and D.J.ing old country tunes from his phone (George Jones, Marty Robbins). His mother, in a blue denim vest and blue suede cowboy boots, was serving up heaping plates of homemade dishes from her native Nigeria (jollof rice, plantains, baked chicken). The night’s performance was sold out, as had been the case for every gig on his fall solo tour. Each Tuesday, Shaboozey was eagerly hitting refresh on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart until new numbers appeared, and each Tuesday he was finding “A Bar Song” still on top. That night, his band would play the song last in its set — and then, as soon as they were done, play it again a second time, and then a third.

He was not a traditional candidate for country stardom. He was born Collins Obinna Chibueze; Shaboozey is a stylized spelling of his surname conferred on him by a football coach. He’s a 30-year-old former rapper from Northern Virginia, a first-generation Nigerian American who got interested in country music via a NASCAR jacket he found in a vintage clothing store. But his third album, “Where I’ve Been, Isn’t Where I’m Going,” launched him squarely into the realm of genuine country success. At last year’s Country Music Association Awards, he played “A Bar Song” on a charmingly dingy honky-tonk set and was nominated for both new artist of the year and single of the year. For the 2025 awards, this month, he was one of the marquee performers — and nominated, again, for new artist of the year.

This is a type of a success that large parts of the music industry seem fixated on right now. Country has surged in popularity: Its U.S. streaming numbers went up 23.7 percent in 2023, and its market share expanded overseas. More visibly, country has conquered new regions of the Billboard charts, including the top spot on the Hot 100: It now spends long stretches in the hands of Zach Bryan or Morgan Wallen, whose 2024 tour sold the fifth-highest number of tickets globally. (Or in the hands of Shaboozey, whose breakout single ultimately spent 19 weeks at No. 1.) Parts of the industry seem to be looking at this market roughly the way they looked at disco in the 1970s or grunge in the 1990s. Early last year, during an event at which the producer Jack Antonoff was honored, the pop star Lana Del Rey — who is expected to release her first country album soon — announced that the music business as a whole was going country. Hip-hop artists, in particular, have often enjoyed easy passage into country, and today you can find former rappers like Jelly Roll and Post Malone playing rodeo crowds; country is such an obviously tempting career lane that you can also find MGK, who began as a rapper and then pivoted to pop-punk, collaborating with Jelly Roll on “Lonely Road,” a single interpolating a John Denver song.

You could credit a lot of Shaboozey’s success to how well he understands these dynamics — the complex lines between country’s traditions and its present, its purists and its interlopers. At one point, talking about why pop artists might find it harder to crack country audiences than rappers do, he turned almost professorial. “Country music and hip-hop are both lifestyle genres,” he said. “Pop music isn’t a lifestyle genre. Pop music is: You write a song, it has a formula, the chorus is here, the prechorus is here. Country music and hip-hop are about the lifestyle. You gotta live this life, and this life comes with a starter pack. You trade that Lamborghini for the F-150; you can change the Amiri jeans for Wrangler jeans; you switch out the Jordans for cowboy boots; you switch out the fitted snapback for the cowboy hat. There’s a parallel between country and hip-hop. There’s certain things that hip-hop artists get away with doing or saying because it’s a lifestyle, and same with country. Because of that, a lot of people are afraid to not fit in.”

Shaboozey has fit in — even more than he expected to. This fall, after a year spent converting a big hit into a more lasting place in the industry, he told me that he gauged his success not by the obvious numbers but by how many people are inspired by his aesthetic or want to replicate it. He had topped Billboard’s country chart with another single, “Good News,” and in the spring he was the only artist to play both the Coachella festival and its country-music arm, Stagecoach. But he seemed more struck by seeing himself reflected in the audience. “The cowboy hat is country,” he said. “But now, especially for people that look like me — they’re like, well, wait, the hair is country! The locs he’s got are country!”

This rise hasn’t been without its awkward spots. During Shaboozey’s first visit to the C.M.A. Awards, he was the subject of several odd jokes — teasing references to his name and parents, or the producer Trent Willmon dedicating an album-of-the-year win to the “cowboy who’s been kicking Shaboozey for a lot of years.” Shaboozey knows that he is not entirely native to country’s world and may be reminded of this fact. “I feel outside looking in sometimes, and I would love to not feel that,” he told me later. “But there’s probably no way for me to fit in fully, you know what I mean?”

There are times when the policing of country’s borders produces some dust-up that draws national attention, like the 2019 debate after Billboard pulled Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” off its country chart or the chilly reception Beyoncé received at the 2016 C.M.A. Awards. But most of this genre-policing does not play out amid big stories or online arguments, or even on radio playlists; it plays out among individual listeners’ senses of what is real and what is fake, whom they relate to and whom they do not. Shaboozey has performed excellently on this test. Last year, at the People’s Choice of Country Awards — held in the Grand Ole Opry House, the beating heart of Nashville’s old guard — he won best new artist. How did that feel, I asked him? “I don’t know,” he said. “I mean, I definitely thought it was a pretty loud response when I won.”

Before the show at the 9:30 Club, Shaboozey’s mother sat in a corner booth, proudly showing off photos of her other two children. The singer’s older sister is a model and D.J.; his younger brother was studying medicine. As we spoke, Shaboozey called across the room: “Did you ask my mom how I started making music? See what she says. I’m curious.”

Earlier that day, inquiries about his upbringing hadn’t revealed much. He mentioned that Woodbridge, Va., the Washington suburb where he grew up, was known for good public schools — and then, when asked if that’s why his parents moved there, shrugged and said, “I don’t know, maybe.” His father worked at a Toyota dealership, and his mother was a nurse who worked nights; both were originally from Lagos, Nigeria. His father came to the United States first, settling in Texas in “the ’70s or ’80s, I think,” the singer said — “I’m not too sure.” Theirs was not the kind of immigrant story that gets endlessly repeated over the dinner table. Shaboozey knew what his parents expected of him: get good grades, go to church, then “go to George Mason or Harvard or something and become a doctor, I don’t know.” He uses words like “disconnected” to describe how he felt at home. Later, he said: “You know how people say, ‘We came from nothing?’ It’s like I came from a different kind of nothing.”

Other artists, he imagines, had parents who said, “Here’s all these vinyls — we listen to Joni Mitchell and Stevie Wonder and stuff.” Over several conversations, he wondered more than once about how he measured up to other subjects. (“Who’s the craziest person you’ve ever interviewed?” he asked. “I’m trying to get a gauge of where I should sit.”) He seemed to wonder what it would be like to have a background that he considered more typical for an artist, instead of being, as he put it, “one of the weird ones.” This surprised me: So far as I have seen, growing up feeling different — frustrated by the limits of your town and convinced that everyone cool knows something you don’t — is pretty much the de facto early consciousness of a future star.

Shaboozey never really planned to be a musician. He wanted to be a filmmaker or a novelist. When he started making music as a teenager in the 2010s, it was mostly rap. But he also felt that the culture of hip-hop had little room for him: By the time he got there, it felt too defined and too out of reach financially, and anyway he wasn’t from one of its established geographic centers. “You know what New York is: It’s Jay-Z and Big Daddy Kane and a big-ass chain and Timbs,” he explained. “L.A. is like, maybe guys are surfing or skating — it’s surfing or skating, and it’s Hollywood glamour. We know what Atlanta is. OK, but what’s Virginia? I got very fascinated by the idea of, I’m from this place, but what is it? When you can’t access those places, you have to become the thing that other people come to.”

In 2014, he was 18 and living at home, making music with a local hip-hop collective. He was planning to move to Los Angeles, both for a girl and to try his hand at screenwriting: He had written a pilot for a show called “Groupie,” based on the notorious 1969 autobiographical novel, which he first tracked down because he saw a photo of Robert Plant reading it. He had a habit, back then, of visiting thrift stores, which he liked to imagine as collections of other people’s stories; he would search for unusual items like ’80s Asics and acid-washed jeans. But he kept finding — and buying — old NASCAR jackets: Jeff Gordon, Dale Earnhardt, an autographed Rusty Wallace. “There’s a reason why you find a lot of those in that area,” he says. “NASCAR started from a place of mundaneness, from people that are just like, Let’s race cars in the mud because we’ve got nothing else to do.” These people, he thought, came from a different kind of nothing.

When he told his parents he had dropped out of community college and planned to head West, they didn’t react the way he expected; they were supportive of his move. But the stakes felt existential: “I think I was very scared of, man, if this is all life was — like, we go to school, and we do this thing every day, and then we go to work, and then you get old, have kids and pass away — this is going to be very depressing.” Those stakes pushed him to self-release his first single, inspired by the first NASCAR jacket he bought. “Jeff Gordon” was not a country song; it was an uneasy, meditative trap track that began with audio from an actual race. Still, he says: “When I made ‘Jeff Gordon,’ I found my identity.”

This identity didn’t translate immediately in Los Angeles. He signed a record deal quickly, in 2016, but neither of his first two albums — “Lady Wrangler,” a rap record that flirted with country signifiers, and “Cowboys Live Forever, Outlaws Never Die,” which sharpened the western theme — got much notice. The industry itself seemed skeptical of the persona he was building: “People thought the cowboy thing was just a gimmick,” he has said. It wasn’t until 2024, as he was working on songs for his third album, that things shifted: Somebody from Beyoncé’s team heard an early version of “A Bar Song” and invited him to appear on her upcoming project. Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter,” a country record with a pop audience, was released that March, and Shaboozey’s presence on two of its tracks surely seeded the turf for the arrival of his own L.P. two months later. But by that point, he had already been looking for the right way to declare himself a country artist for the better part of the decade.

Of all the walls that have broken down between country and pop, the most important ones may have been built on pop’s side. Since the advent of Napster, kids have grown up mainlining major records from just about every genre — but a certain barrier lingered around country, which was still seen as being for country-music people. That barrier has since collapsed. When I spoke with Stacy Vee, a power player in country’s concert industry and the executive behind the Stagecoach festival, she quoted a line from a colleague about listeners outside of country’s home territory: “It used to be if you listened to country music, you would roll your windows up. But now they’re not even streaming this music in secret.” In a New York magazine cover story about the culture of the “West Village girl,” one source described the archetype as being into Cartier bracelets, Hugo spritzes, Sabrina Carpenter — and Morgan Wallen.

Even fashion has spent the past few years starting to go country. Pharrell Williams sent cowboys in embroidered jackets and chaps down the runway at a Louis Vuitton show; Miu Miu sold a $695 cowboy hat that Elle named the it-girl accessory of the summer. As for Shaboozey, he attended the Met Gala dripping in turquoise, and the online fashion magazine Highsnobiety ran an article analyzing a paparazzi photo of him leaving the apartment of a rumored celebrity girlfriend, calling his outfit “the perfect confluence of country-fried comfort and of-the-moment street sleaze” and his style not merely “Westernwear-lite” but full “cowboycore” luxury.

Shaboozey likes to muse about the mysterious calculus that determines how this kind of stardom is made. “Everything that works against me also works for me,” he told me at one point. “I have a theory — like, an equation — when it comes to this,” he said in another conversation. “There’s a meter, and certain things fill up that meter.” For him, “it’s the country-music thing, being Black, being Nigerian, having this name.” A meter that’s half or even a quarter full, he said, might pique somebody’s interest. But “a lot of these major artists have broken that meter, and the needle has gone haywire,” he said, citing acts like the Weeknd, Doja Cat, Chappell Roan and Sabrina Carpenter. This was the company he was seeking to keep.

When we first talked last year, Shaboozey was still in the early phase of his rise; he seemed both shy and distracted. He didn’t open up until he started talking about Pink Floyd and revealing ambitions broader than music. “They had their album, but then they also made this movie,” he said. “In music, you can make music videos on the internet, you can do concept albums like Pink Floyd — that’s what I want to do.” We were in another hotel restaurant; he paused to squeeze lemon into his tea. “My approach is different than most artists in this position,” he said. “It’s not like I have this deep passion for singing and writing songs. I just like making things, however I can.” And indeed, every conversation we had about musicians he admired was also full of references to film, literature, fashion; his explanation of the “texture” he was seeking when he started making music, for example, mentioned country acts and NASCAR jackets, but also Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of the S.E. Hinton coming-of-age novel “The Outsiders” and James Dean. He used to dream, he said, of merging his influences into one epic project, like “a concept album where every song ties into the next thing, and it’s set in the 1800s, in the Old West.”

A few weeks ago, I spoke with Shaboozey while he was on tour in Australia, where he has had two hit singles; audiences seemed excited for their first chance to see him, though he was surprised to find them unfamiliar with classic country songs, like a Hank Williams cover that usually had Americans singing along. After a year of award nominations, festival appearances and stadium tours with Jelly Roll, he sounded more confident and expansive than ever. He told me he had been listening to “Johnny Cash Sings the Ballads of the True West” and Willie Nelson’s “Red Headed Stranger,” along with a lot of bluegrass. He had been hanging out in Montana and watching westerns. He was working on his next album, which he said would be different, grander. “When I started, I was like: Man, there’s no way anyone’s going to give me the money. This is too ambitious for a new artist,” he said. “But now I’m like, Hey, I want to do this. It could be a huge loss to everyone involved, or it could be one of those pieces of art that people are really inspired by.”

We had talked about this before, in Cincinnati. How he never felt entirely at home anywhere. How he dreamed of synthesizing his favorite things to create a world in which he would truly, uniquely belong — not breaking into someone else’s realm, but becoming, as he said, “the thing that other people come to.” All sources of inspiration seemed open to him. “Marty Robbins,” he said, “when he’s telling tales of the Old West — he didn’t live in the Old West. He died in, like, 1960-something. Or John Wayne’s making these movies, but he didn’t live in these time periods. You see something that inspires you, and you make it your own.”

He gestured at my motorcycle jacket. “You have a leather jacket on,” he said. “That was inspired by somebody. You didn’t invent that.” Right, I said — and Shaboozey certainly wasn’t the first Black artist to wear a cowboy hat. “Yeah, no,” he said. “But I will say this: I didn’t see a lot of them, you know what I mean?”

The post Why Are So Many Pop Stars Trying to Win Over Country Fans? Ask Shaboozey. appeared first on New York Times.