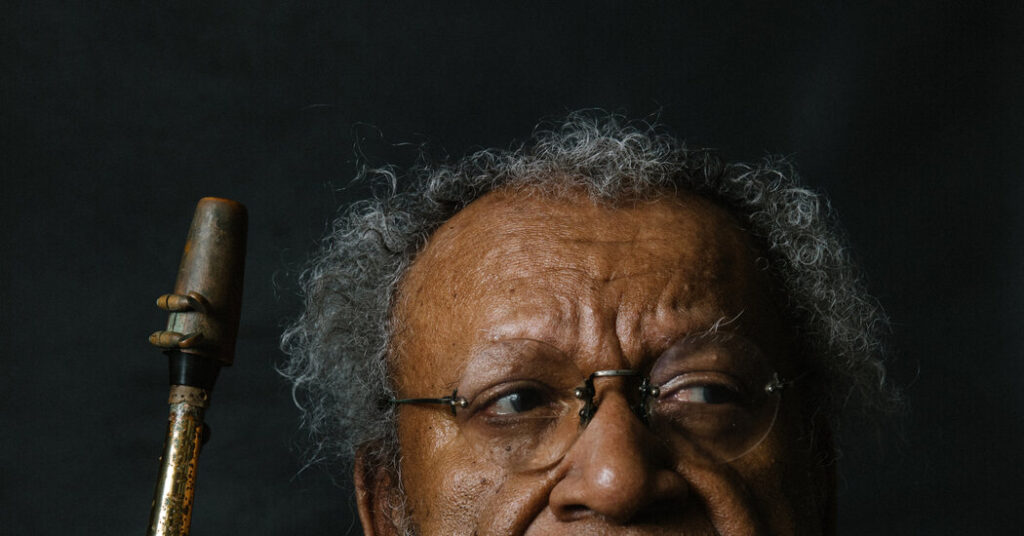

Anthony Braxton turned 80 in June. And although this irreplaceable composer and performer hasn’t been making appearances with his reed instruments of late, in some ways there has never been a better time to get curious about his vast output.

That’s because his multivalent creativity has never been more widely available. For example: “Trillium X,” Braxton’s recent four-act opera, landed on disc and digital formats following its 2023 premiere in Prague. The publisher Schott released some intriguingly laid-back experimentalism from Braxton’s “Thunder Music” system — also first presented in 2023, by the Darmstadt Summer Course in Germany. And a recording of the latest improvised collaboration between the saxophonist and the noise band Wolf Eyes has also hit the catalog.

That may seem like enough, yet there’s been even more from Braxton’s six-decade archive. Six hours of absolutely febrile 1985 concertizing by one of Braxton’s most swinging, “classic” quartets were released by Burning Ambulance.

Then there’s Braxton’s pedagogical side. His trilogy of “Tri-Axium Writings” received new paperback editions this year. These hefty, idiosyncratic (note the spelling) collections of philosophy and cultural critique were first published in the 1980s but had been long out of print, and Braxton’s Tri-Centric Foundation worked on the new editions.

OK, that’s probably enough.

Except it hasn’t been at Roulette in Brooklyn, where Braxton was celebrated across three Wednesdays in November. At these shows, hard-core fans and recent initiates gathered to hear some true rarities. (All the concerts are available to stream for free on Roulette’s website and YouTube channel.)

The first concert, on Nov. 5, was both the tightest and the widest-ranging, in terms of composition style and the years covered. As an opening act, the saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock and the pianist Shinya Lin interpreted Composition No. 101, from 1981. Braxton recorded this duo piece multiple times — once with Giorgio Gaslini, the composer behind the languid jazz score for Michelangelo Antonioni’s film “La Notte.”

Laubrock and Lin didn’t rehash past glories. They began with some open improvisation, and when they started Braxton’s score, they took advantage of his standing invitation to “kick it about.”

Lin’s contributions involved more inside-the-piano work and prepared-piano riffing than Gaslini once ventured. Laubrock switched between multiple saxophones, and her tone on soprano had some of the precise, biting quality of Braxton’s playing. But she also produced gentler sounds of bop-adjacent balladry during moments on tenor.

After intermission, eight members of Braxton’s handpicked Tri-Centric Vocal Ensemble convened to create a collage-style set of multiple works. Throughout that performance, the chugging nonce-phonemes of some “Ghost Trance Music” pieces for voice collided with scenes from the Braxton opera “Trillium J” (also known as Composition No. 380). That’s a heady way of saying the set involved a wild mix of tones and timbres. But again, there was a precision to the way these artists found freedom together.

The International Contemporary Ensemble’s show on Nov. 12 wasn’t as successful. Although the group gamely embraced music from multiple decades of Braxton’s creative practice, the resulting mosaic didn’t communicate enough of his exploratory joy across those eras.

Instead, the show’s highlight involved the way the International Contemporary players profitably engaged with two pieces by the guitarist Mary Halvorson — a former student of Braxton’s and a longtime collaborator. During Halvorson’s “Belladonna,” for string quartet and electric guitar, the soloist Dan Lippel crafted a winning, personal take on the part that Halvorson herself usually plays (as on her recording for Nonesuch).

The final concert, this week, was one that no Braxton fan should miss. Laubrock returned, this time in partnership with Cecilia Lopez; together, they delivered polish and invention during Composition No. 38 (for saxophone and electronics). But the high point was a rare performance — in full robed regalia — of Braxton’s first “ritual and ceremonial” piece, Composition No. 95 (“For Two Pianos”).

Why ritual? Braxton has written: “My original intention when composing this work was that I sensed and felt that the next immediate cycle in social reality promises to be extremely difficult — and there is danger in the air for all people and forces concerned about humanity and positive participation.”

Ursula Oppens premiered this work with the composer-pianist Frederic Rzewski in 1980, and the Arista label subsequently issued a studio recording by the pair.

On that vintage release, you can hear Braxton the composer synthesizing many points of inspiration, sometimes by sequentially rotating ingredients. Stockhausen is in there. (The composition notes refer to “moment forming tendencies.”) And some of Braxton’s early participation in the Philip Glass Ensemble may have also had some bearing on this or that stretch of repetitive patterning. Braxton also refers to Webern, so the Second Viennese School seems an acknowledged forebear. But the thickest moments of harmony are something else entirely — perhaps blended with the enthusiasm of someone who may have once enjoyed listening to Cecil Taylor play a version of Billy Strayhorn’s “Johnny Come Lately.”

In his notes for this piece, Braxton writes that unstaged performances of it may be all well and good, but that the work’s impact is heightened in a live performance that follows his intended staging elements.

On Wednesday, Oppens partnered with the younger pianist Adam Tendler to bring all those aspects alive. They embraced the theatrical components — say, when strumming zithers or playing melodicas near each piano, or when gesturing underneath their ceremonial robes. But they also did justice to the music itself. It sounded less nervy than the Oppens-Rzewski take but was plenty energetic and mysterious. The day after the concert, I asked Oppens about performing the piece 45 years after its premiere.

“The piece is very much about playing together, and as Adam and I worked on it we became more and more responsive to each other’s energy,” she wrote in an email. “Adam is of course a very different artist from Frederic and quite ebullient. The piece feels both more cohesive and more adventurous than when I premiered it 45 years ago. I also understand more how the different sections work in relation to each other. I loved playing the extra instruments and the sound world they opened up.”

It takes time, in other words, to process the Braxton philosophy, the notes on the page and his exhortation to “kick it about.” But the more you see how these elements interact, the more Braxton you’ll probably want.

The post At 80, This Composer Is Easier Than Ever to Celebrate appeared first on New York Times.