Back in the ’80s, when slick pop and hair metal began to consume all, a hard-drinking group of ragged Minnesotan rockers continued to show up some nights ready to play and some nights not. They were a mess, or they were the greatest live band ever, or sometimes they were both at the same time.

But one thing was undeniable: Of the seven records the Replacements left behind, none was better than 1984’s “Let It Be.”

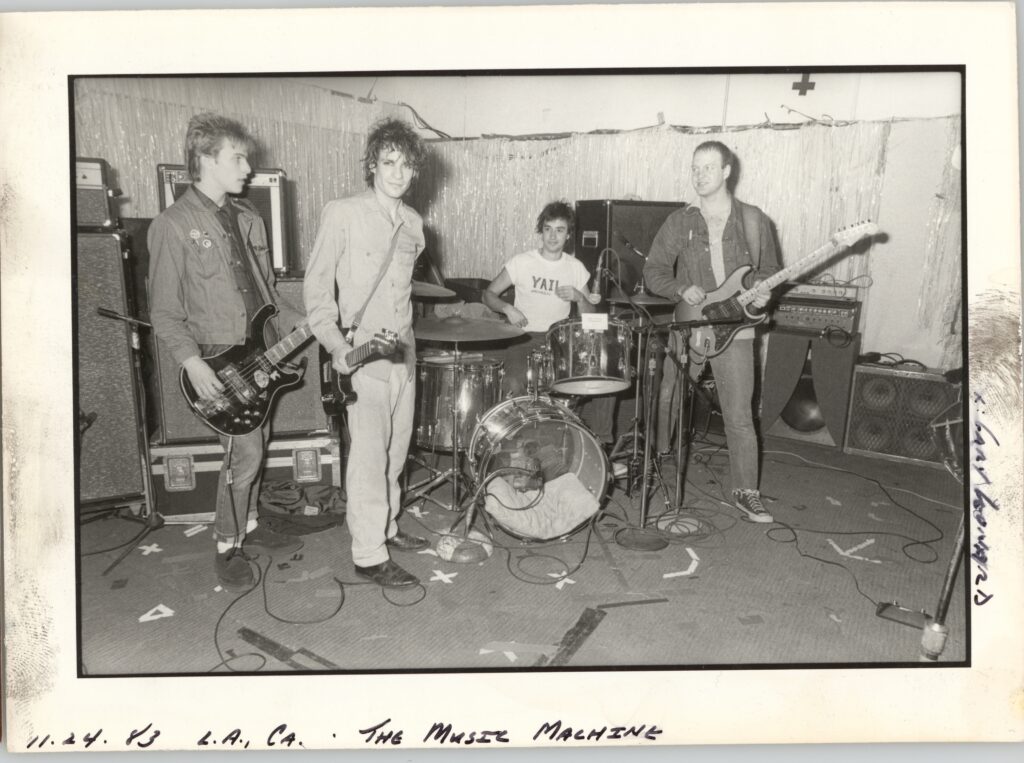

In that moment, singer Paul Westerberg, drummer Chris Mars and the Stinson brothers — guitarist Bob and bassist Tommy — hit a sweet spot between chaos and creativity. It wouldn’t last, of course, as record-label pressures and recreational medications took their usual toll, driving Bob out of the band and eventually leading to their big split in 1991. “Let It Be” remains the Replacements’ high point, delivering a special brand of post-teen mischief and melancholy with classics such as “I Will Dare”and “Unsatisfied” that turned Westerberg into the greasy-haired, slacker king of the Winona Ryder set.

This week, Rhino delivers a “Let It Be” box set that beefs up the original record with rarities, alternative versions of released songs and a typically craggy gig from Chicago’s Cubby Bear club. (There’s also an excellent essay from D.C.’s writer/singer Elizabeth Nelson.)

Because it’s the Replacements, the publicity rollout of “Let It Be” is, er, slightly unconventional. Westerberg, at 65, is “retired,” according to his representative, and not doing interviews. (I did, truth be told, attempt an end around by mailing the serious baseball fan a personal letter and signed Topps card of 1970s Twins catcher Butch Wynegar; Westerberg never replied.) Bob Stinson died in 1995, age 35, after years of drug abuse. Mars, 64, and Tommy Stinson, 59, did agree to talk about “Let It Be,” though they hadn’t heard the set yet, and Stinson said he wasn’t likely to listen to it.

“I kind of lived it, you know, a hundred years ago,” he said by phone from Montreal, where he’s recording a new album.

Mars, a successful painter over the last three decades, has generally declined interviews about the Replacements. He had a change of heart after watching Rhino revisit the band’s back catalogue in recent years. “Everybody’s working so hard on these packages, getting them out,” he says, “and I really appreciate the effort, so I said, ‘I’m going to help out.’”

In separate interviews, Mars and Stinson talked about the dynamic that led to the creation of “Let It Be,” the chaotic brilliance of Bob Stinson, and whether the band’s resident genius, Paul Westerberg, will ever be heard from again. These interviews were edited for space and clarity.

I want to walk up to “Let It Be” and the fact that the Replacements started out as a kind of punk band. Your earlier records, “Stink” and “Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash,” were thrashing.

Chris Mars: Around that time, we were sort of co-billing with a lot of the hardcore bands. So there was a lot of slamdancing, and the other bands just kept getting more and more crazy and fast. And I felt like we, for a moment, tried to fit in with that a little bit.

But you were never Black Flag or Circle Jerks.

Mars: No, we’re not, and I think it was at [the Great] Gildersleeves in New York, if my memory serves me, maybe with Husker Du, and I think on this night we were warming up, and the crowd was yelling, ‘Faster.’ We weren’t up-tempo enough for them at that time. And so then we just looked at each other and broke into Hank Williams, “Hey, Good Lookin’” And they were just booing. And we were just laughing. And I think that moment to us was more punk than punk was.

What were you listening to leading up to “Let It Be.”

Tommy Stinson: Funny enough, Aztec Camera was a really big one for me. Roddy Frame was a great guitar player, great songwriter. I was into the Clash pretty big time then. And I was really kind of going backward into, like, Slade and, you know, the glam rock stuff from back in the early ’70s. And of all the crazy things, I think Kate Bush, around that time. I know Paul was into that, too.

Mars: When it comes to the van, anything and everything. Big Star was a thing that was getting played a lot at that time. At home, I was listening to Elvis Costello and the Clash. And I liked the music on both of those things particularly, but I really liked the drumming.

Bob was such a key part of the Replacements. He would basically be out of the band by 1986, but explain what made him so important on “Let It Be.”

Mars: Most drummers play with the bass player. I learned how to play with Bob Stinson before any of the other guys joined the band. Bob had just a great sense of rhythm, and he could jump on the drums and play the drums … I remember distinctly, we’re doing “I Will Dare” and working that out, and then Bob comes out with the lick. [Sings the guitar melody.] And it’s like, that made the song.

We tend to think of Bob as this damaged, out-of-control guy, but I’m also listening to a song like “We’re Coming Out,” and he just makes it come to life, or even “Unsatisfied,” a ballad, and he’s playing tasteful licks that fit perfectly.

Mars: There was a “Live at Maxwell’s” thing that came out, and there was a little bit of footage online. I was just reminded of Bob and how he could be really, really tight and just really quick with the fingers. But also that chaos where it was like a storm. It wasn’t like your [standard] lead that hit all the notes. He would, like, start on a note and get weird in the middle, and then somehow end up in the right place.

Stinson: That entire record was probably Bob at his peak. And I think what happened after that is he lost his way and basically lost his way with all of us. Suddenly he’s in another place. I mean, drugs and alcohol do that.

I assume there was a huge difference once Bob was no longer in the band and Slim Dunlap joined.

Stinson: Uh, Slim didn’t fight back. Bob, he wasn’t really into a lot of things that we were starting to do. I think Paul was feeling like, ‘I’m growing, my songs are going this way, and you’re going that way.’ Without speaking for Paul, the way it ended up was exactly that.

So, Paul. I think he made his last record in 2016, the one with Juliana Hatfield. We haven’t heard from him much since. Do you ever nudge him as his friend and say, ‘Hey, why don’t we do something?’ Don’t you miss that voice?

Stinson: You know, I tried to do that in the past, and it hasn’t worked out so great, and I think he’s just on his own trajectory to be Paul and the way he feels like he wants to be. You’ve got to tip your hat to him — it’s like he’s doing what he wants, whatever that is. When he wants to do something else, you’ll hear about it, I’m sure.

Mars: The last time I saw him was a few months back. I was on my way up through the city and said, “Hey, I’m going to just pop in and see if Paul is around,” and he was, and we hung out a bit and, you know, I think we’ve said everything we’ve ever needed to say over a very compressed, intense time over 10 years. … We talk about e-bikes, cause we’re getting older now.

Do you have an e-bike?

Mars: I do. And where I live, there’s paths all over the place.

Does Paul?

Mars: He does have one.

Not to go off subject, but when you talk to Paul, do you ever talk about music? Is he really retired?

Mars: We maybe touch on it a little bit. “How you doing? Are you recording anything?” It’s pretty much, “Nah,” and he’s got his amps in the garage. I know he has a piano set up. And there was one time I was working on a song a couple of records ago — “Down by the Tracks.” I kind of had the melody, and I remember we were waiting for Tommy to call. And I was over at Paul’s, and he hopped on the piano, and I was playing this song and kind of humming it. And we were kind of having fun there for a second. And then the phone rang, and it all ended.

The post The moment it all clicked for the Replacements — before it fell apart appeared first on Washington Post.