For those who have smartphones, credit cards and bank accounts, a cashless world makes life faster and easier — less time counting exact change at the checkout counter; no need to stuff crumpled-up bills in pants pockets.

With the rise of tap-to-pay and digital payment apps, many people now carry less cash, especially more affluent Americans. According to a 2022 Pew survey, about 60 percent of adults with household incomes of at least $100,000 said that none of their purchases in a typical week are paid in cash, as opposed to 24 percent of those making less than $30,000.

But in New York, that convenience can come at a cost. An entire economy of people still relies on cash — street performers, food vendors, candy sellers, the homeless and others who are struggling.

Rob Brender is disabled and has been panhandling for most of the past decade. He likes to post up near stores, where a steady current of people pass by. “I can’t deal with rejection,” he said, so he doesn’t stop anyone or shout out asking for money.

Instead, “I sit in the street with a cup for change and I listen to 104.3 and I rock it out,” he said, adding, “This is how I’ve been getting by.”

But lately, though there seem to be endless shoppers, the cash hasn’t been flowing into his cup.

Mr. Brender, 55, who lives in a group home at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, said his friend made him a sign with a Venmo username written on it, but no one has stopped to use it, and he doesn’t even know how to access his account.

New Yorkers of all backgrounds are noticing how the shift is affecting their interactions.

Marty Burns, a 32-year-old architectural designer and educator, said he often forces himself to remember to bring cash when he leaves his apartment.

“If you have cash and you feel like you can contribute, as a person traversing New York, towards, say, a street performer or someone at Grand Central, you do feel less isolated from the community,” he said. “Having cash allows us to express support for each other in a small way. It allows us to be more present.”

Lost Interaction

Riva Dhamala, a 29-year-old designer, said that she had felt more connected with people in the city when she used to carry cash. But now, with the spread of Apple Pay, using cash is often a hassle. There are an estimated 65.6 million Apple Pay users in the United States, according to Capital One Shopping, a figure that is expected to grow to over 84 million by 2030.

“It feels like the message that I’m receiving externally is, ‘Be as fast as you can, inconvenience everybody as little as possible,’” Ms. Dhamala said. “And it feels like the way to do that is by using Apple Pay.”

Think of the person who sighs as someone writes a check at the grocery store, or the people in line rolling their eyes at the person taking the time to count out bills from their wallet.

Digital payment methods create “enclosed, gated communities,” said Ursula Dalinghaus, a cultural anthropologist at Ripon College. But when you hand someone cash, she added, “you’re having a human connection” with money that is “not tied to a device or a particular account.”

Jules Katz, 28, works at a start-up and doesn’t even carry a wallet anymore. She simply keeps her credit card and ID in her phone case, she said. When she is with her mother, who usually does have cash, she’s noticed that she’s able to engage more with buskers in the city. On walks in the park together, “we’ll stop and give the guy who plays the sax a dollar,” she said. “It does feel a little bit more interactive.”

Many performers have signs that display their Zelle, Venmo or Cash App information to receive tips. But that comes with the friction of pausing and carefully punching in their username, or scanning Q.R. codes. And there are privacy concerns, too.

Barriers to Banking

In 2020, New York City barred businesses from refusing cash payments. Many stores did not immediately comply, including the popular ice cream chain Van Leeuwen, which later settled with the city.

But for many vendors, the opposite situation is all they know: They only accept cash.

Mohamed Attia, the managing director of the Street Vendor Project at the Urban Justice Center, worked as a food vendor for nearly a decade after emigrating from Egypt in 2008. He said that the instantaneous nature of cash is often necessary.

“It takes a few business days for the digital transactions coming in to show up in the balance, and that is limiting to a vendor who needs to go purchase more supply and restock their business,” he said.

For several years, Mr. Attia only accepted cash. It was difficult to make time to get set up with an e-payment system. “It’s one person doing everything,” he said. “I have to be at the garage at 4 o’clock in the morning, prepare the cart, drive the cart to the spot, set up the cart to do the business, shop the fruits and veggies and get everything ready, do all the vending and then take the cart back to the garage. My day would be between 14 to 16 hours, so to add more tasks would be a huge issue.”

Sometimes, a customer would place an order, and only afterward would they realize they didn’t have cash to pay Mr. Attia. He’d tell them: “I’m not going to let you go hungry. Take the smoothie and pay me next time.”

Eventually, his business grew, and with additional business partners, Mr. Attia operated four smoothie and halal carts around Manhattan. Around 2018, “we realized that we were starting to miss out on a lot of customers,” which is when they decided to install digital payment systems.

He has been helping vendors around the city get set up with such systems.

“A lot of folks have been struggling, especially those who are not comfortable having a bank account or cannot even get into banking because of their immigration status,” he said, pointing out that 96 percent of vendors are immigrants. “The vast majority of these financial institutions are monolingual, and they assume that every client who walks in will be speaking English, and it’s intimidating for an immigrant who’s not very comfortable in English.”

With how many different transaction apps there are, for vendors, it can feel like an endless loop of downloading, signing up and cashing out.

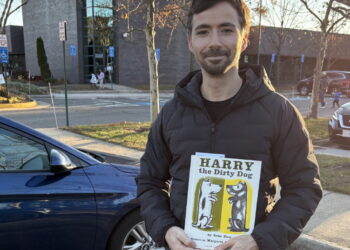

This has been a struggle for Richard Morant, who sells his artwork on the sidewalk by the Prada store in SoHo.

A potential customer would say, “‘I have PayPal,’ and I was like, ‘OK, I don’t have that,’ so I got PayPal,” Mr. Morant, 41, said as he stood in front of his charcoal eye drawings. “Then another would say, ‘I don’t have PayPal, I have Cash App.’ So I had to get Cash App. Then, ‘I don’t have Cash App, I have Zelle.’ It kept going.”

He added, “We need cash.”

‘Please Help Me, Thank You’

On a recent Friday afternoon, Wilbert Rodriguez, 56, sat on the sidewalk across from the Aritzia store in SoHo. Behind him, a woman twirled in a bridal gown as a photographer snapped photos, and a flurry of tourists rushed from boutique to boutique, shopping bags in hand. In all the chaos and movement, Mr. Rodriguez remained still, holding a cup of change as he said on repeat: “Please help me, thank you. Please help me, thank you.”

Mr. Rodriguez, who said he is unable to work because of an injury, lives in a Safe Haven shelter. He doesn’t always like the food there, so he asks for change on the streets until he’s collected $10 to $15, enough for a bacon, egg and cheese sandwich and an orange juice. It usually takes him the entire day to get that much. “No one has cash, what can I do?” he said. “Whoever got it, got it. Time is changing. I don’t want to do this forever.”

In an increasingly cashless world, some New Yorkers are still finding ways to help those in need. On the 6 train headed uptown, a woman handed tampons to another who said she was homeless and needed help. Outside a restaurant on the Lower East Side, someone gave a cigarette to a man who asked for a dollar.

On rare occasions, Mr. Brender said, someone will still go out of their way to help him, too. “They’ll say, ‘Look, I don’t have cash, but let me buy you something in the deli,’” said Mr. Brender. “And I’ll be like, ‘Sure, roast beef and Swiss.’”

Anna Kodé writes about design and culture for the Real Estate section of The Times.

The post A Tap-to-Pay Society Is Leaving These New Yorkers Behind appeared first on New York Times.