Stuck in pur-gut-tory?

Several factors can contribute to constipation, from certain supplements and vitamins to dehydration and lack of movement.

But there can even be microscopic reasons for why you can’t go — specifically, the type of bacteria that’s living in your gut.

When the balance of gut bacteria is disrupted, it can cause several issues, such as irritable bowel syndrome, bloating, diarrhea and constipation.

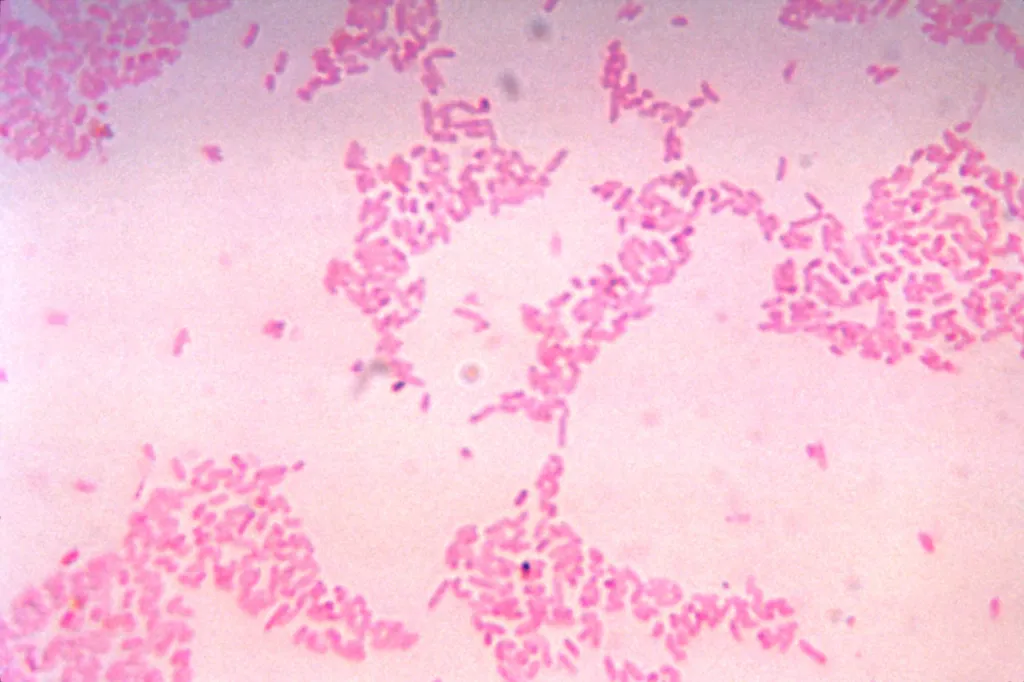

Now researchers in Japan have identified two common bacteria that, when present at high amounts, can back things up in the bathroom.

The research, published in the journal Gut Microbes, found two bacteria that are harmless on their own, but can team up to thin the protective mucus layer that keeps stool soft and moving.

While Akkermansia muciniphila and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron are both supposed to exist in the gut, it’s when there are elevated levels of both that issues start up.

This thinning and drying out of the gut’s natural lubricant has been dubbed “bacterial constipation.”

Under normal circumstances, the gut needs both bacteria to function properly.

The gut’s mucus layer retains water and lubricates stool to keep everything moving smoothly, while preventing the gut lining from coming into contact with bacteria living inside it.

A. muciniphila feeds on colonic mucin that carries chemical sulfate tags that most bacteria can’t get past. However, it needs help to do this.

This is where B. thetaiotaomicron comes in, to produce enzymes that remove the sulfate tags, which opens up the mucin for A. muciniphila to break down.

While this whole process is necessary, over time the mucin begins to thin, moisture drains from stool and bowel movements slow down.

Higher levels of these bacteria are often found in those with Parkinson’s disease and chronic idiopathic constipation.

To determine how this constipation happens, researchers looked at mice without any gut bacteria.

The ones given only one of the two types showed no signs of constipation, while mice given both had fewer stool pellets, drier feces and lower mucin levels.

The researchers also discovered that deleting a single gene in B. thetaiotaomicron reversed constipation, meaning that bacteria’s sulfatase activity no longer allowed gut mucin to let bacteria in.

The researchers suggest that measuring fecal levels of A. muciniphila, particularly alongside the partner bacteria, could help identify who’s likely to suffer from this type of constipation.

The post Having trouble pooping despite trying everything? You might have ‘bacterial constipation’ appeared first on New York Post.