My wife and I recently became the legal guardians of a teenager, and we are struggling with how to ethically navigate the emotional complexities of this arrangement.

We met this person through our children’s athletic community. They come from an extremely difficult situation involving neglect and emotional abuse. A year ago, we offered them our home temporarily. As we learned more about their circumstances, we decided to pursue legal guardianship until they turn 18. We have no familial ties — we simply wanted to offer stability, safety and a chance at a better future.

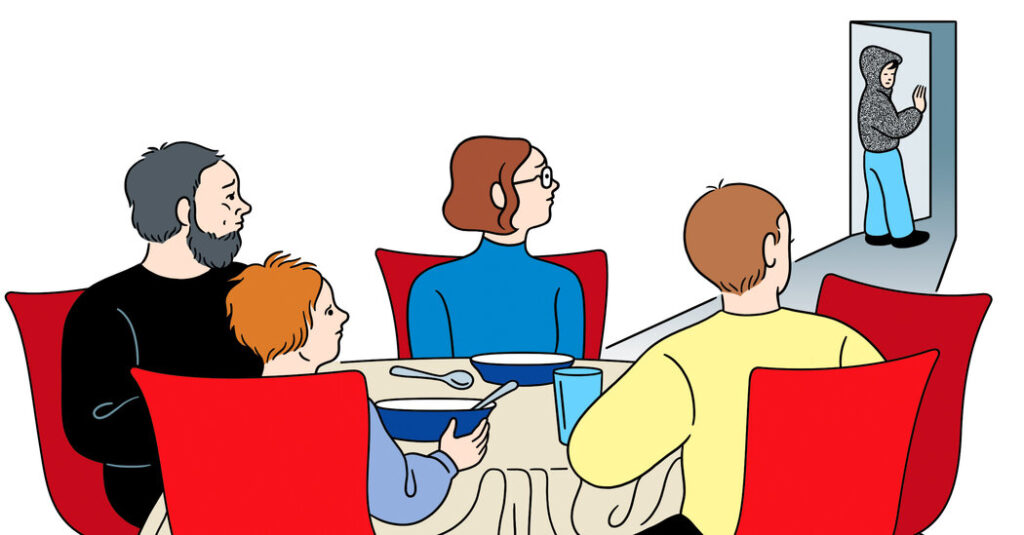

From the beginning, we agreed with our ward that we would treat them as we treat our own children — same expectations, same privileges and full support. For a few months, this arrangement seemed to be working: Our ward’s grades improved, they joined family activities and outings and appeared to settle into the rhythm of our family life. Then, little by little, they withdrew from us, no longer spending time with the family, and started getting worse grades again.

Our ward has indicated that we intervene too much in their life and has complained to others that we’re “suffocating.” We’ve made adjustments — offering alternative meal arrangements, allowing them to stay with trusted friends on occasion and making space for their independence. Still, the distance has widened.

Our children, meanwhile, are asking about the increasingly different standards at home. And without meaning to, I’ve found myself carrying negative feelings that I don’t want but can’t quite shake.

My wife and I are about to engage in therapy with our ward. I am not looking forward to it; I worry that even in that safe space, I will not take well the possible complaints and criticisms we may hear from them.

What obligations do we have — beyond the legal ones that we’ll meet — to our ward, and to ourselves, as we navigate a painful emotional landscape? And what moral, economic and emotional obligations should we anticipate when they turn 18 and become independent with no real support network? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

However much you have done for this young person, they had a life before coming to live with your family, and their feelings for you are probably not going to be those that your children have. Those feelings may change, but not on any timetable you can control. And your ward’s expectations about your role in their life will have been affected, as well, by the inadequate parenting they have left behind. It’s natural for you to feel that this person owes it to you to keep their side of the agreement you reached. But it’s also natural for teenagers to resent those responsible for raising them and, in the biblical cadence, to “kick against the goads.”

In this teenager’s case, these normal yearnings for independence will be complicated by the knowledge that they are indebted to you and by the sense that you could give up on them in a way you would not give up on your own children. There’s some emotional logic to pre-emptively pulling away and testing your tolerance. After all, they’ve already been let down by one set of adults.

I understand why the family therapy you’re about to engage in feels daunting. The complaints you will hear are going to sound like ingratitude. If the therapist is any good, though, the sessions will allow you to explore and explain your feelings, too. Everyone’s expectations may need a reset. Psychologists sometimes talk about the “martyr-beneficiary” dynamic, where resentment flares on both sides, and obviously it would help if such resentment could be dampened. But the practical goal would be to agree on a few nonnegotiables, not to indict or vindicate anyone.

Beyond safety and stability, what you owe your ward, and yourself, is to provide structure: rules about school attendance, basic courtesy and the like. But just as their feelings aren’t the kind of deliverables you can negotiate, neither are yours; you can’t be obliged to provide an emotional simulation of a happy family. As for the questions you’re getting from your own children? You can discuss with them why you decided that accommodations had to be made for someone who experienced trauma and transition.

What you’ll owe this person when they reach legal majority will depend, in good measure, on what commitments you make in the next year or two and what expectations you encourage them to develop. A lot of this will be up to you. The relationship you have with them may or may not gain genuine warmth. Once you reach into a person’s life in the way you have, however, you shouldn’t just abandon them — though you should be prepared for the possibility that they will decide to abandon you.

Readers Respond

The previous question was from a reader who was reluctant to assume leadership of his family’s business because it would mean working with his difficult cousin. He wrote:

I joined my family’s company, and it has been messy. The main shareholders are my mother and her two sisters. From my generation, there’s a cousin who also works here. He’s complicated, with a history of anger issues and past verbal aggression toward employees and family. … Right now, disagreements end with my mother, the chief executive, making the final decision. What worries me is what will happen once she steps down. My mother has said that she sees me as the person best suited to lead the company, and she’s convinced that my cousin should not. She also reminds me that she has invested a great deal of time, money and effort in preparing me for this role. I like the company and have learned so much from being here. The work is challenging and fulfilling. But I can’t picture spending the rest of my career working with my cousin. … What are my obligations in this situation? — Name Withheld

In his response, the Ethicist noted:

When someone habitually communicates anger through intimidation, withdrawal or physical displays, I’d say it qualifies as a workplace problem. Make sure your mother, the chief executive, is fully informed about what this man does, how often and its effects on the team (including you). If your mother has settled on you as her successor, then she and the other shareholders should establish clear expectations for your cousin’s role, including behavioral requirements. … It sounds as if you don’t think you’d be able to fire or discipline this cousin even if you were the chief executive, given the shareholder arrangement. That’s why this problem needs to be confronted while your mother still has the standing to secure the other owners’ backing. She has invested a lot in preparing you for leadership, and this has weight. It doesn’t give her a majority stake in the rest of your career.

(Reread the full question and answer here.)

⬥

Time for the letter writer’s mother to create a viable, workable succession plan, in consultation with the company’s attorneys. It needs to be pretty much bulletproof. Who has the higher rank in the organization: son or cousin? Maybe the mother can promote the letter writer to a position of authority that would allow him to have some H.R. responsibility over his cousin. Having a fair and clearly written employee manual that outlines acceptable and unacceptable behavior would also help. If the letter writer’s mother understands that it will be a good thing for her legacy, she’ll buy in. — Nancy

⬥

Ownership in a private company often implies employment, as is the case with this cousin, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Someone can be a passive owner, and be entitled to a share of the company’s profits, without being entitled to a job. This will be a challenging conversation, but the impact it will have on other employees, not to mention customers, make it one worth having. — Michael

⬥

There are quite a few consultants who specialize in family-business succession issues, and they are effectively a combination of therapists and business advisers. As someone with experience advising family businesses, I think such a consultant could be extremely useful in this situation. They would serve as an outsider who can communicate the hard truths, thereby maintaining family relationships. — Susan

⬥

Relatives who aren’t pulling their weight, or are disruptive, are not an unusual problem in family companies. What’s needed is regular outside evaluation of all family members in their job context, by someone who isn’t the mother of one of them. It appears that in this case, the cousin is already receiving special treatment, and other employees have undoubtedly observed this. An employee who behaved that way in my company would get a private counseling opportunity, and then be sent on their way if they didn’t shape up. — Paul

⬥

All family businesses are fraught with similar problems when it comes to succession planning. Our family business is currently being run by the second generation, with the third generation just coming into consideration in the last few years. With Generation 2, it was an expectation that we would work for the family business. But that was over 25 years ago. Now we realize that to attract the Generation 3 talent, we need to make it desirable for them — it can no longer be an expectation, as letter writer’s mother seems to think. Life is too short to carry out someone else’s dreams at the expense of our own. — Cindi

The post We’re the Guardians of a Difficult Teenager. What Do We Owe Them? appeared first on New York Times.