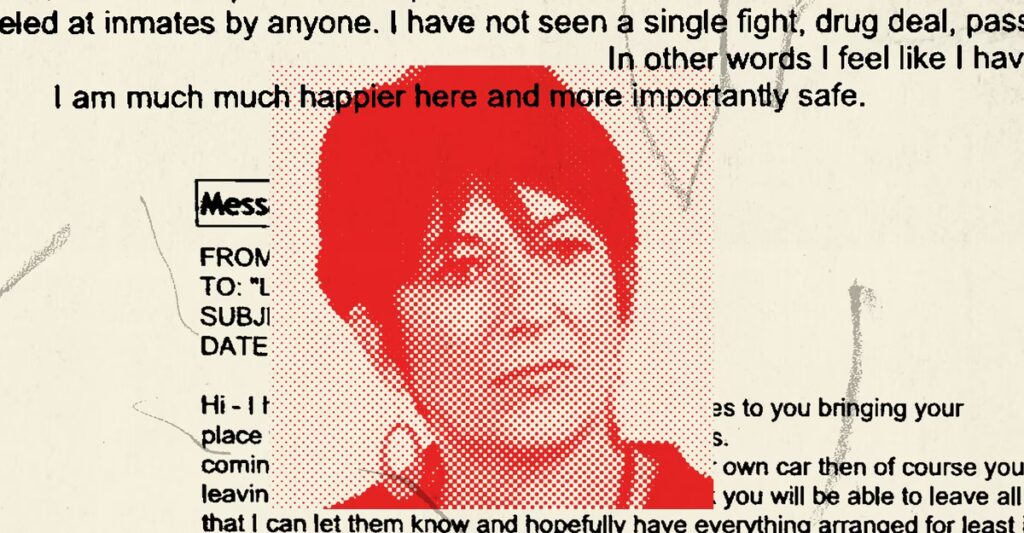

The emails that Ghislaine Maxwell has been sending over the past several months from a minimum-security prison near Houston are stamped Sensitive But Unclassified. Maxwell once cavorted with presidents and royals; now she’s serving a 20-year prison sentence for sex trafficking, convicted of recruiting underage girls for Jeffrey Epstein. Her trajectory is not a happy one.

But the tone of the emails is cheerful. She revels in the privileges she’s been granted since being transferred to a new facility by Donald Trump’s Justice Department, and she expresses optimism about one day freeing herself. While telling family of her improved conditions, she remarks that Croatia is one of her favorite vacation destinations. Among the ebullient expressions that appear in the disgraced British socialite’s messages, mostly to her siblings and one of her lawyers: “Yippe skipee” (about her brother’s upcoming visit), “I hear you are a media star!” (in reference to another sibling publicly defending her), and “it gladdens the cockles of my heart” (when she heard from an old friend).

The dozens of emails that I obtained, part of a cache of communications that a nurse at the facility provided to Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee, are notably free of regret, remorse, shame, self-doubt. Portions of the emails have been disclosed in recent days, including by NBC News, but the extent of the privileges Maxwell enjoys has not previously been reported. The emails offer a portrait of Maxwell’s relatively comfortable life as the scandal that put her behind bars has gripped Trump in a political vise. The problem for the president arises from his administration’s determination to block public access to files about Epstein that he once dangled to the MAGA faithful like some kind of rap sheet for the global elite. This week, he backed down when it became clear that he couldn’t intimidate a sufficient number of Republican lawmakers—grudgingly reversing himself and then claiming credit for legislation compelling the release of the files.

[Read: The Trump steamroller is broken]

In July, Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, who previously served as Trump’s personal defense attorney, took the highly unusual step of visiting Maxwell behind bars. While there, he elicited this exculpatory observation from the Epstein accomplice: “I never witnessed the president in any inappropriate setting in any way.”

Days later, Maxwell was transferred out of a Florida prison, where she had dealt with poor conditions, including “possums falling from the ceiling,” as she would later recount. Her new home was the Federal Prison Camp in Bryan, Texas, a minimum-security facility that Bureau of Prisons guidelines deems inappropriate for sex offenders. Since arriving there, she’s benefited from a number of unusual perks, according to the emails as well as people with knowledge of her circumstances who spoke with me on the condition of anonymity.

She is receiving visitors privately, in the prison chapel, instead of in the regular visitation space. Her lawyer has gained authorization from the warden to bring in private electronic equipment, and her legal team has had access to drinks and snacks while working with her. Her privileges extend to more intimate needs. Whereas other inmates receive just two rolls of toilet paper a week, and need to either buy more or resort to paper towels when those run out, Maxwell has received a special supply. Her access to communications appears uninterrupted, even when the prison’s main phone lines are down. In August, her brother marveled that they could be in “virtual real time communication.”

Certain benefits may seem more trivial than others, and family members of Maxwell’s fellow inmates told me the scandal is not what she has been allowed, but rather what their loved ones have been denied. Local defense attorneys I consulted, including some who have represented inmates at the facility where Maxwell is being held, were most alarmed by the wide-ranging assistance that the warden, Tanisha Hall, appears to be providing Maxwell as she seeks early release. Maxwell has praised the warden in emails to family, saying Hall is “as good as they come.”

What did the warden do to earn Maxwell’s affection? Among other things, the inmate’s emails suggest, Hall provided Maxwell with secretarial services. When a problem with the mail arose in September, as Maxwell worked to find a way out of jail, the warden came up with what the inmate called a “creative solution”—her attorney could scan documents and email them directly to the warden, “and she will scan back my changes!” The following month, Maxwell was typing away late one Sunday. She was wading through attachments, and she was “struggling to keep it all together,” she wrote in an email with the subject line “Commutation Application,” suggesting that her team was preparing a direct appeal to Trump. As they worked on their argument, Maxwell told her lawyer that she would transmit relevant records “through the warden.”

Trump, who once socialized with Epstein and Maxwell, hasn’t ruled out a pardon for her. When Maxwell was first arrested, in 2020, Trump told reporters, “I wish her well, whatever it is.” In a letter earlier this month, Congressman Jamie Raskin, the top Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee, wrote a letter to Trump demanding to know whether his administration had discussed a commutation of Maxwell’s sentence, as well as whether his advisers had arranged for the inmate’s special treatment in prison. “You should not grant any form of clemency to this convicted and unrepentant sex offender,” Raskin wrote. “Your administration should not be providing her with room service, with puppies to play with, with federal law enforcement officials waiting on her every need, or with any special treatment or institutional privilege at all.”

[Read: Trump told a woman ‘Quiet, piggy’ when she asked about Epstein]

Congressional Democrats have also sought answers from Hall, the warden, who did not respond to my questions. A Bureau of Prisons spokesperson told me in an email that the agency “is committed to maintaining the highest standards of integrity, impartiality, and professionalism in the operation of its facilities,” and that allegations of preferential treatment are “thoroughly investigated.” The most severe repercussions thus far have befallen Noella Turnage, the prison nurse who sent the emails to Raskin’s office and was soon fired. She told me that she was raised in a conservative Republican family and was motivated not by politics but rather by outrage over Maxwell’s own account of her cozy relationship with the warden. In a statement, a Maxwell attorney condemned Raskin for disclosing the correspondence, saying it was the latest example of her client’s “constitutional and human rights being ridden roughshod over.”

Doug Murphy, a prominent Houston-based attorney, likened the warden’s solicitousness with Maxwell to the CEO of a major company dealing directly with a customer’s needs. “It’s way out of the norm,” he told me. He said he could imagine only two possible explanations. The first, which he deemed unlikely, is that the warden has a special relationship with Maxwell. The second is that she was directed by superiors to provide leniency to the convicted sex offender.

“And that would be really concerning,” Murphy said.

When Epstein was arrested on federal sex-trafficking charges, in 2019, not many people outside rarefied social circles knew the name of his former companion. Her father was a British publishing tycoon whose mysterious death in 1991 generated headlines, but that hardly made her a household name. Even when Epstein pleaded guilty to soliciting a minor, in 2008, Maxwell didn’t draw much scrutiny.

That all changed when Epstein was arrested on federal charges and then found dead in his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in Lower Manhattan. Maxwell had withdrawn from public life several years earlier, but she quickly became a stand-in for the legal accountability Epstein had evaded. And, according to prosecutors, she had plenty of culpability in her own right. At trial, the government portrayed her as a knowing accomplice to Epstein’s crimes, a predator in her own right who established trust with a ring of girls only to offer them up to Epstein, sometimes participating in the molestation directly. Her defense team argued that she was being blamed for things that Epstein did. In 2021, a jury in New York found her guilty of sex trafficking and other charges. The following year, she was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Maxwell was initially held at a federal detention facility in Brooklyn, but then transferred in the summer of 2022 to a low-security prison in Tallahassee (populated by women convicted of kidnapping and providing material support to terrorism, among other charges). Maxwell complained of poor conditions there, describing the facility as “lawless.” She tried to make do, teaching yoga and Pilates and helping other inmates with legal work.

[Read: How I came to be in the Epstein files]

This past summer, her fortunes began to change as senior members of the Trump administration worked to tamp down a political crisis created when they failed to live up to their own extravagant promises about exposing the monstrous conduct of Epstein and those in his orbit. Attorney General Pam Bondi, who had once claimed on cable television to have a client list from Epstein sitting on her desk, said in early July that the government would make no further disclosures from its investigation. Meanwhile, evidence of Trump’s associations with Epstein mounted; The Wall Street Journal reported that Trump had contributed a racy letter to a book compiled by Maxwell for Epstein’s 50th birthday, in 2003.

Amid the fallout, Blanche, the No. 2 at the Justice Department, wrote on social media that he would meet with Maxwell in search of “information about anyone who has committed crimes against victims.” Over the course of a two-day interview in late July, Maxwell said she was unaware of a much-discussed client list and denied knowledge of Epstein’s abuse. She also heaped praise on Trump, not only absolving him of improper conduct but also saying, “I admire his extraordinary achievement in becoming the president now. And I like him, and I’ve always liked him.” She said she first met Trump in the early 1990s, through her father, who also “liked him very much.”

FPC Bryan, as Maxwell’s prison is known, houses about 650 women. It’s surrounded by a black fence, not particularly tall or imposing. People locked up inside have been convicted of crimes including embezzlement and fraud. Two of the more well-known inmates are Elizabeth Holmes, the Theranos founder convicted of defrauding investors, and Jen Shah, the former Real Housewives of Salt Lake City star who pleaded guilty to wire fraud.

Maxwell arrived late on the final day of July, receiving her medical check-in outside of normal hours. Other inmates began complaining instantly that she was receiving preferential treatment, including delivery of special meals. Hall, the warden, told inmates not to confront or harm her, and threatened to ship them to a harsher facility if they stepped out of line. An inmate who told the British newspaper The Telegraph that she was “absolutely disgusted” by Maxwell’s presence was quickly transferred, the inmate’s attorney, Patrick McLain, told me. McLain said it’s “unheard of” for inmates to get the kind of treatment Maxwell is receiving: “Wardens do not get involved with individual prisoners like this.” Maxwell has credited the warden for the conditions at the Texas facility, which she said represents a major improvement over “Tal”—the Tallahassee prison.

“The food is legions better, the place is clean, the staff responsive and polite.” It was safer, too, because “you are not allowed to steal, beat people up and attack them with home made weapons.” She felt she was finally on the right side of “Alice in Wonderlands looking glass,” she wrote to her brother. “I am much much happier.”

Maxwell tried to keep a low profile. She instructed her brother, “You should look like a lawyer visiting me :).” But her attorney at times seemed to delight in the attention she was receiving. She clued Maxwell in on paparazzi outside the prison fence. One of the photographers lying in wait was “one of the best,” she told Maxwell, “if not THE best!”

[Read: Wait, are the Epstein files real now?]

When she first got to Texas, Maxwell was waiting to find out whether the Supreme Court would hear her case. “I am quietly confident that the Supreme Court case is worthy and valid and has an excellent shot,” she wrote in August. In the meantime, she worked feverishly with her attorney, writing in an email that the warden “would rather that I sent all the updates through her.” In another message, she told her attorney that the warden had records ready for her team to pick up.

She followed other legal proceedings closely. In early October, she remarked on the four-year sentence handed down for the music mogul Sean “Diddy” Combs, who had been convicted on sex-trafficking charges. “Hmm,” she wrote, seeming to suggest that his punishment was lenient compared with hers. Days later, the Supreme Court declined to hear Maxwell’s appeal, making commutation, or some other form of clemency from Trump, her last best hope of relief from her lengthy sentence.

Maxwell wrote cryptically in some of the messages, as if aware that they could one day be disseminated. In one, she expressed concern about a meeting with an unnamed individual, cautioning her attorney, “If something is too good to be true then it isn’t.”

On other matters she was more confident, including her ability to advocate for herself. She seemed to enjoy strategizing with her attorney about her case, like a puzzle that could help her pass the time. She allowed herself optimism about finding a solution. “I have faith,” she wrote.

One day, she imagined, she would not only be released; she might even get her own law license. To that expectation, divulged to her attorney, she appended a playful smiley face.

The post The Ghislaine Maxwell Emails appeared first on The Atlantic.