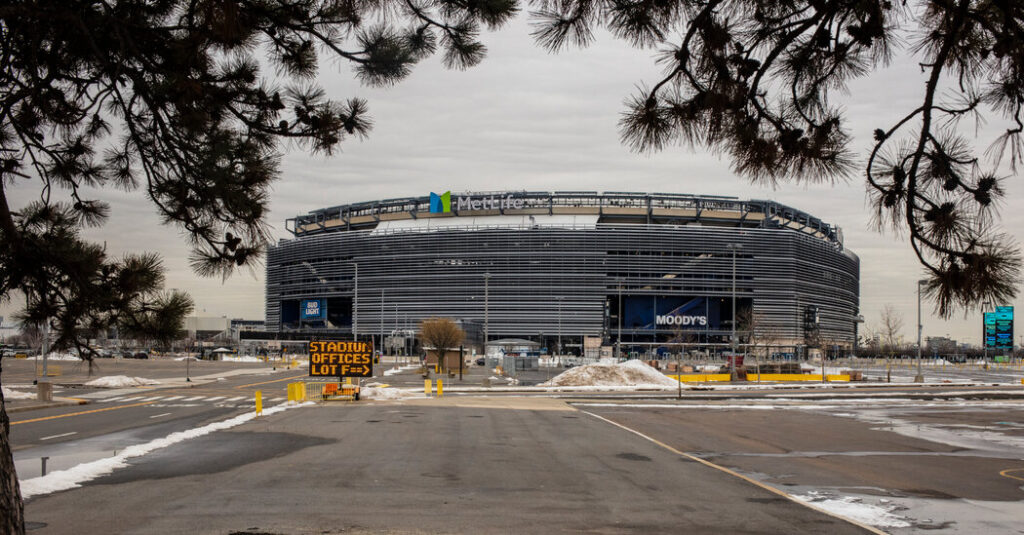

This time of year, MetLife Stadium sits dormant in the middle of a vast parking lot at the far end of New Jersey’s ninth congressional district. But in just four months, it is expected to come alive as host to a boisterous, colorful sporting festival with hundreds of thousands of fans arriving from around the world to attend soccer’s World Cup.

Organizers have envisioned a well-attended, exciting and lucrative event in 16 cities across Mexico, Canada and the United States. The capstone event will be the final game, which will be held at MetLife Stadium, in East Rutherford, N.J., on July 19.

But in recent days, federal officials confirmed what had previously been the subject of speculation: that ICE agents will be at the World Cup, too. For some, that revelation raised fears that the typical scenes of revelry and celebration could be replaced by images of tear gas and batons.

“It’s going to cause chaos, that’s what I think,” said Representative Nellie Pou, Democrat of New Jersey, whose district includes the stadium.

It was Ms. Pou who posed questions about the World Cup to Todd Lyons, the director of ICE, at a congressional hearing this month in Washington. She found his answer — that ICE, “specifically Homeland Security Investigations,” is a “key part” of World Cup security — disconcerting.

Mr. Lyons did not rule out using the militarized, tactical teams of agents who have inspired protests in Minneapolis, where federal agents shot and killed two U.S. citizens during its operations. ICE, which already has a presence in the region, also has an investigative wing that Mr. Lyons referenced. Homeland Security Investigations has been involved in security at large events domestically and abroad for years, including Super Bowls and the Winter Olympics in Milan, largely without notice.

In an email, Tricia McLaughlin, the outgoing spokeswoman for the Department of Homeland Security, said that international visitors who came to the United States legally would have nothing to worry about.

“What makes someone a target for immigration enforcement is whether or not they are illegally in the U.S. — full stop,” she said. “Speculation to the contrary is ill-informed.” Ms. McLaughlin stressed that visitors should start working on their travel plans now, “to ensure a smooth travel experience.”

Millions of World Cup fans are expected to travel to North America, and with a capacity of 82,500 at MetLife Stadium, several hundred thousand could be headed to the New York/New Jersey region, though exorbitant ticket prices could exclude even the most eager fans.

Ms. Pou (pronounced POE) spoke this week at her office in Paterson, N.J., a working-class town with a large Spanish-speaking population. She was born and grew up in Paterson, with parents from Puerto Rico who met in New Jersey. She is bilingual in English and Spanish, and while not a devoted soccer fan, is aware that many of her constituents are.

She is also a member of the congressional Committee on Homeland Security and the ranking Democrat on a task force charged with ensuring security at big events, including the World Cup.

Ms. Pou says that because of ICE’s “draconian” methods, even U.S. citizens and others who are in the United States legally, have been victims of wrongful arrests. Some soccer fans, she noted, may worry that even if they are in the United States lawfully, they may still be mistakenly arrested and swept into a murky system of detention.

Some people have even called for a boycott of the World Cup over the Trump administration’s policies, which would certainly diminish the $3.3 billion economic boon projected by the New York New Jersey World Cup 2026 Host Committee.

“My concern is that they won’t come,” Ms. Pou said of the fans. “And if they don’t come, that will be a problem, not only for my district but for our country.”

Along with the World Cup final, MetLife Stadium is scheduled to host eight games, starting June 13. Teams with first-round matches in New Jersey include Brazil, Morocco, France, Senegal, Germany, Ecuador, Panama, Norway and England. Many businesses in the diverse ninth district are excited to welcome the global influx.

Caffè Roma, a small Italian coffee spot in East Rutherford, is nearly three miles from the stadium. But Michael LoBue, the owner, says that when the wind is right, he can hear the roar of the crowd at football and soccer games and music from concerts. He is expecting more business during the World Cup, and he said he had no concerns about ICE scaring people away.

“We show all the soccer games on the TVs here, and a lot of my customers love it,” he said. “I don’t think there will be any problems.”

A few blocks away, a restaurant worker, originally from Mexico City, felt differently. He said his name was Daniel and that he was in the United States legally, but he asked not to give his last name for fear of deportation anyway.

During a break from work, he said that he had friends who might go if they could get tickets. He wouldn’t go regardless.

Mr. LoBue, the café owner, noted that during recent international soccer events at MetLife stadium, including last summer’s Club World Cup and the Copa América in 2024, a large video screen set up blocks from his coffee shop drew fans who wanted to watch the games in a communal setting.

Similar events are expected in many cities during the World Cup, especially in the New York and New Jersey region. Ms. Pou is worried that those sites could also be targets for ICE raids.

She said she understood the need for safety, but stressed that state, local and federal agencies already have ample experience at the stadium, not only for international soccer games, but for the New York Jets and New York Giants football teams and for concerts.

“There’s a huge event every week,” she said. “It’s not our first rodeo.”

David Waldstein is a Times reporter who writes about the New York region, with an emphasis on sports.

The post Will ICE Scare Some Fans Away From the World Cup? appeared first on New York Times.