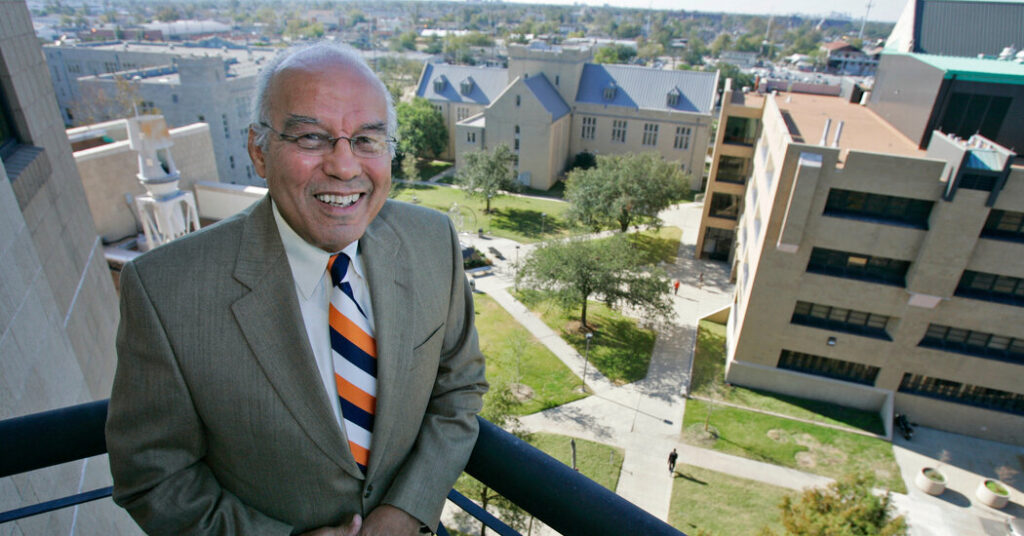

Norman Francis, the first Black president of Xavier University of Louisiana, who played an important role in the civil rights movement in New Orleans, died on Wednesday in Jefferson, La. He was 94.

His death, in a hospital, was announced by his family.

Mr. Francis was a pioneer several times over in a city that accommodated itself only sluggishly to civil rights.

In 1952, he was the first Black student to integrate the law school at Loyola University. “It was something you had to do,” he told an Xavier interviewer in 2019. “The goal was really to shake up things, and let’s start being serious about civil rights.”

Then, in 1968, he broke a four-decade tradition of white nuns serving as president of Xavier. By the time he retired from the university in 2015, after 47 years, he had become America’s longest-serving college president.

Under his leadership, enrollment doubled, the endowment grew to about $161 million from $2 million, and the school — the only historically Black Catholic institution of higher learning in the country — turned into a powerhouse for producing Black medical students; Xavier is consistently cited for sending more Black students to medical school than any other four-year college in the U.S.

As a young lawyer Mr. Francis defended, in court, student protesters affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality, who had staged sit-ins at a segregated New Orleans lunch counter. Their case was ultimately won at the Supreme Court.

When the Freedom Riders, young civil rights workers integrating bus lines, arrived in New Orleans battered and bloody in 1961, Mr. Francis, already an administrator at Xavier, sheltered them in a dormitory and held a news conference to celebrate their arrival.

In 1970, when Moon Landrieu was elected mayor of New Orleans, determined to integrate city government, Mr. Francis, a friend since their law school days, became his adviser on all matters relating to civil rights.

“Norman helped guide him through that the whole way,” Mr. Landrieu’s son Mitch, himself a former New Orleans mayor, recalled in an interview. “There wasn’t a difficult issue that Norman Francis didn’t give him advice on. Counsel, advice, suggestions, guidance — it wasn’t like, a little bit.”

Moon Landrieu also appointed Mr. Francis chairman of the city’s civil service commission.

“Down in the arena is where things happen,” Mr. Francis said in the 2019 interview. “Up in the galleries are the critics. They fight no fights. They’re not going to move a finger to change it.”

Norman Christopher Francis was born on March 20, 1931, in Lafayette, La., the fourth of five children of Joseph Abel Francis and Mabel (Coco) Francis.

His father was a barber who had worked as a bellhop at the city’s leading hotel and as a railroad worker. Mr. Francis grew up poor — he began working at 10, delivering lunches — in a Catholic household that placed great value on education.

He recalled in a 2002 interview for The HistoryMakers, an oral history project, that in Lafayette, the capital of Louisiana’s Acadiana region, the rigors of the Jim Crow South were eased somewhat by the shared language, French, that was spoken by both Black and white people.

But the commonality only went so far. His father, Mr. Francis recalled, “was the byproduct of a white father and a Black mother,” adding that it was “one of those unfortunate instances that happened in the turn of that century, where his mother was taken advantage of.”

Mr. Francis graduated from St. Paul Catholic School as valedictorian in 1948, and received a scholarship to attend Xavier, with a work-study job in the school’s library. He was class president each year, and graduated in 1952 with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

On his first day at Loyola Law School that year, Mr. Landrieu was one of a trio of white students who came up to him.

“Those three guys walked up to me and said, ‘We want you to know that if you ever need a friend, we’re going to be your friend,’” Mr. Francis recalled in a 2013 interview with The New York Times.

Law school was formative for him. “It erased forever, if I had any doubts, about whether I was talented enough to compete with another race that was felt by others to be superior,” he said in the 2002 interview.

He received his law degree in 1955, and joined the U.S. Army, serving in the Third Armored Division in Germany. Mr. Francis then joined Collins, Douglas and Elie, a pioneering Black law firm in New Orleans that represented the Congress of Racial Equality and other clients, and he became dean of men at Xavier in 1957.

He accepted the position of president of the university on the day the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968.

When, two years later, Mr. Landrieu was sworn in as mayor of New Orleans, he had carved out a special symbolic role for his old friend, introducing him before he took the oath of office.

“Here you had an assembly on the grounds of City Hall, all the policemen, all of the public officials,” Mr. Francis recalled in the 2002 interview. “But who steps up to the microphone to say, ‘I’m now about to introduce the next mayor of the city of New Orleans?’ His classmate, who is Black.”

After Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, when the Xavier campus was inundated by as much as six feet of water, Mr. Francis rushed to get the flooded school on its feet and resume classes, and the school was back in operation less than six months later.

Gov. Kathleen Blanco appointed him chairman of the Louisiana Recovery Authority, the government agency responsible for coordinating planning and rebuilding in the aftermath of the storm. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush in 2006.

He married his wife, Blanche, in 1955; she died in 2015. Mr. Francis is survived by his sons Michael, Tim, David and Patrick; his daughters Kathleen and Christina; a sister, Mabel Bailey; and 11 grandchildren.

He remained perplexed throughout his life by the foolishness of racial prejudice, and was determined to combat it. In 2002, he recalled an episode from his childhood when his father and some friends built a coffin for a white neighbor whose family was too poor to afford one.

“I guess it has followed me all of my life, which I’ve spent trying to eliminate, if you will, the effects of what was created by Plessy v. Ferguson,” Mr. Francis said, referring to the landmark 1896 Supreme Court decision establishing segregation in the U.S.

He added, “And trying to change the hearts and minds of people about who we are, and why we’re all one and the same, ultimately.”

Sheelagh McNeill contributed research.

Adam Nossiter has been bureau chief in Kabul, Paris, West Africa and New Orleans and is now a writer on the Obituaries desk.

The post Norman Francis, Who Led Xavier University Into a New Era, Dies at 94 appeared first on New York Times.