If you have ever felt that the American political landscape resembles some kind of nightmarish circus, you may find catharsis in the new play Kramer/Fauci, in which the writer and AIDS activist Larry Kramer faces off with a C-SPAN caller wearing a yellow inflatable chicken suit.

It’s a grand touch of surrealism in a play that makes theater out of one of the most quotidian sources imaginable: an hour of C-SPAN footage from 1993. The script is drawn word for word and um for um from that broadcast, in which Kramer and Dr. Anthony Fauci, then one of the country’s leading AIDS researchers, debated the impediments to finding effective treatments for what Kramer furiously deemed a “plague.”

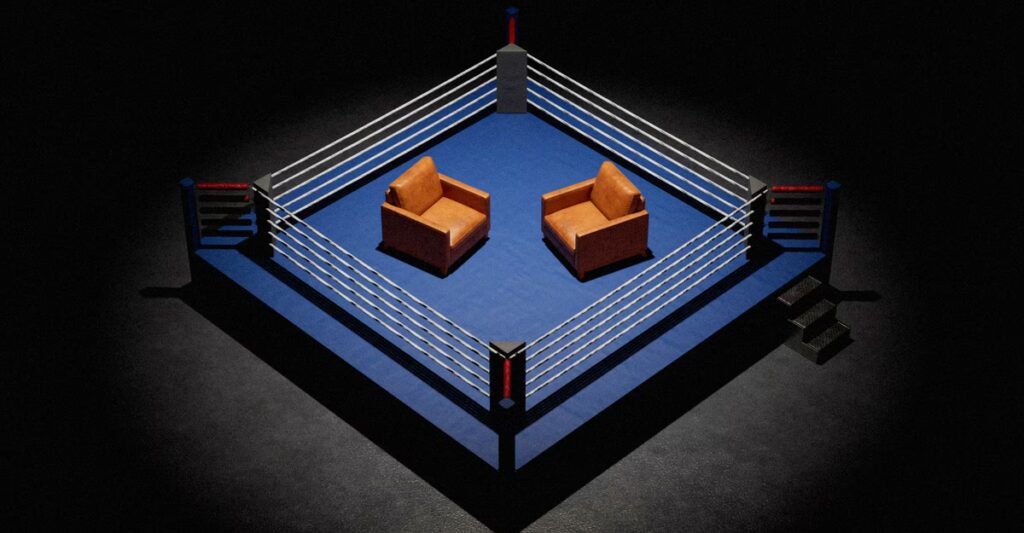

The chicken suit is not a feature of the original broadcast. Neither is the machine that, partway through the play, noisily turns the stage into a great berg of foam, which slowly subsumes a resigned Kramer. In a work that is otherwise remarkably true to fact, those two audacious intrusions ask the audience to contrast the earnest engagement between Kramer and Fauci with the cheap carnival rules to which some viewers in this cynical age may expect them to adhere. This is America in 2026: Debate is supposed to be a gaudy, brash show, a game of big winners and big losers. What are these two dorks doing—respecting each other?

From the earliest days of this nation’s founding, debate has made for a distinctly American type of theater, an art that shapes both civic life and public entertainment. It’s a form that marks the intersection of two profound national interests: showmanship and democracy. The great 1858 debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas as they squared off for an Illinois Senate seat—drawing crowds as large as 10,000 as they did—remain a model for high-school orators today because they are an education in performance as much as statecraft.

Playwrights have long been drawn to that tradition. Inherit the Wind, a play that is widely read in the American school system, sets up a courtroom debate between two legal titans as its centerpiece. Hamilton reframed verbal clashes among the Founding Fathers as rap battles. But in recent years, as American political debates have turned ever more into exhibits of vicious, mudslinging opposition rather than genuine ideological engagement, theater makers have gradually started to ask more pointed questions about the mixed legacy of this patriotic form. How did the kind of public contest that helped shape this country, they have seemed to wonder, go quite so awry?

Hence Kramer/Fauci, the latest installment in the director Daniel Fish’s ongoing effort to find a new layer of meaning in great American texts. His 2019 Broadway revival of Oklahoma turned a show beloved as a celebration of the bright, enterprising nature of the American spirit into a menacing exhumation of the nation’s instinct toward self-mythologizing intolerance. The 1993 C-SPAN exchange between Kramer and Fauci is, perhaps, not quite so well known as Oklahoma. But it is a great American text all the same: an example of the kind of productive, open-minded disagreement responsible for much of what has made this country remarkable.

Kramer and Fauci weren’t on opposite sides of an issue, precisely: During the debate, they agreed that AIDS was a disaster that needed to be a top governmental priority. But Kramer was outside the government, with friends dying, blisteringly aware of the ways in which the official instinct toward bureaucracy was dragging out a scientific process that needed to be moving at, to quote a more modern enterprise, warp speed. Fauci was inside the beast. They spoke different languages—Kramer, that of outrage and urgency; Fauci, that of cautious, measured progress. And so they clashed.

[Read: Larry Kramer knew that an honest debate was a rude one]

That difference could make it sound like they despised each other—or, more accurately, like Kramer despised Fauci, whose rhetorical comfort zone has always been diplomacy. Not so. The duo’s relationship had started out contentious, with Kramer lambasting Fauci in the press as a “murderer” and “incompetent idiot.” By the time of the C-SPAN broadcast, the two men had known each other for years and developed a deep mutual respect and affection. “I think I probably have a more complicated relationship with Tony than with anybody in my entire life,” Kramer says, late in the play. “He is a man, an ordinary man who was asked to play God and he is being punished because he cannot be God. And that is a terrible situation to be in to be the lightning rod for all of us.”

There’s an emotional dissonance to watching Thomas Jay Ryan, as Kramer, deliver that message. He’s speaking from a place of absolute desperation: He’s furious that Fauci isn’t being given infinite resources for his fight, and furious that Fauci won’t get furious alongside him. But the effect of his words, for a contemporary audience member, is something like real hopefulness. It’s refreshing to remember that people at political odds can actually talk about one another like that: with a degree of understanding and compassion that emphasized, rather than detracted from, the moral urgency they felt.

Alas, exchanges like Kramer and Fauci’s were airing on staid C-SPAN, while network TV had already pivoted toward a flashier mode, in which open conflict became a sure formula for success. James Graham’s 2021 play Best of Enemies, viewable online through the United Kingdom’s National Theatre at Home, examines that transition through a series of 1968 debates, televised on ABC, between two writers: the conservative William F. Buckley Jr. and the liberal Gore Vidal. (Buckley is a popular subject: His 1965 Cambridge debate with James Baldwin—about the subject of race in America—has also been revived on stage in recent years.) The thesis of Best of Enemies is aptly distilled by one wry observation about the ABC debates’ dramatic success with viewers: “People like blood sports.”

[Read: The famed Baldwin-Buckley debate still matters today]

The blood-sport mode of debate stands in loud contrast to that of Lincoln-Douglas, and also that of Kramer/Fauci. It is about winning by whatever means necessary. The idea that audiences should leave the debate with a clearer sense of what the best future for the country might be, and how to get there, is nowhere to be found. When Buckley resorts to shouting, “Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi,” he’s embodying the most effective form of the approach he and Vidal were in the process of popularizing. He’s also helping establish a template for the kind of poisonous interchange that has since become so dominant in American discourse. If social media had been around in the ’60s, it’s easy to imagine “you queer” going viral in much the same way as did Donald Trump’s assertion that Hillary Clinton was a “nasty woman” in a 2016 presidential debate.

That, I think, is really Graham’s point, and, in a more indirect way, part of Fish’s. In a moment when success is measured in eyeballs reached, the motivations that first inspired the prominent role of debate in American society have been inverted. Lincoln and Douglas needed to educate first, and entertain second: To win a seat, one of them had to prove he had good ideas, and also that he was better at delivering them than the other. Today entertainment has become the foremost order. “Thank you very much for the discussion,” a moderator in Best of Enemies observes after a particularly riveting blowup between the rivals: “There was a little more heat, and a little less light, than usual.”

But there’s a fresh element to Fish’s approach. Kramer/Fauci doesn’t just hold up a mirror to this specific symptom of societal decline. It also poses a bold thesis: We were wrong the whole time. A great, impassioned, thoughtful conversation can make for entertainment as gripping as Buckley and Vidal’s rage matches. The kind of quiet friction that slowly moves the nation forward can be as compelling to watch as the toxic clashes that have driven it back.

Thus, the yellow chicken. It’s a reminder that we are all in the circus; it is useless to pretend otherwise. But we can choose how much attention to devote to it. Kramer reacts to its surprise appearance with complete disinterest; he is too focused to be distracted by a cheap trick. The challenge to the audience is to do the same: to look away from the alluring absurdity because, in the end, it doesn’t mean anything. Kramer and Fauci—their honorable disagreements, their curiosity about each other’s worldview, their good-faith debate—were the real show, all along.

The post An Antidote to the ‘Blood Sport’ of American Debate appeared first on The Atlantic.