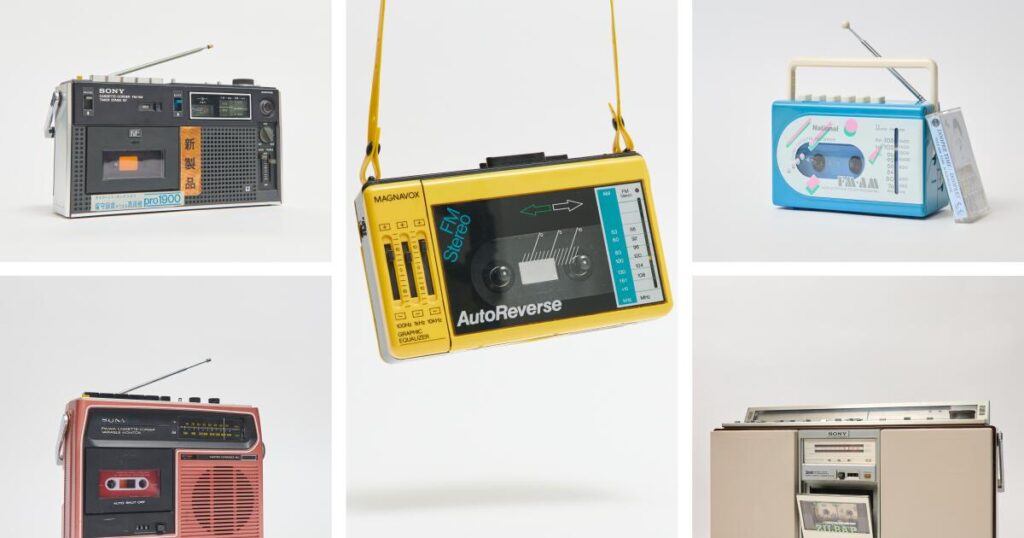

Stepping into Jr. Market boutique in Highland Park is like entering a 1980s time warp. Built into a refurbished shipping container, it’s filled with everything from tiny Walkman-style portables to colorful, number-flip clock radios and, naturally, boomboxes of all sizes. Few are more imposing than the TV the Searcher, a Sharp boombox from the early ‘80s that features a built-in, 5-inch color television.

“Try lifting it, it’s really heavy,” warns Spencer Richardson, the shop’s owner. Indeed, the machine is at least 15 pounds without the 10 D batteries that power the unit. He adds, “I don’t think you’re taking this to the beach so you could watch TV while you listen to music.”

An affable, hyper-knowledgeable proprietor in his early 30s, Richardson repairs and resells analog music technology from the 1980s or earlier. In bringing these rehabbed players back into circulation, he’s helping others rediscover a musical format once left for dead. While his hobby-turned-side hustle started as “a gateway to discover sounds” that he otherwise would not have heard, it now attracts curious customers willing to drop $100-plus for a vintage Technics RS-M2 or My First Sony Walkman. His customers include older baby boomers and Gen X‑ers nostalgic for the players of their childhood, but most have been millennials like himself, drawn to something tactile and analog in an era when everything else disappears into the digital ether.

Unlike turntables, which have become increasingly high-tech thanks to the “vinyl revival” of the last 20 years, almost all cassette players in current production rely on the same, basic tape mechanism from Taiwan, Richardson explains. Though cassette culture is enjoying its own period of rediscovery — albeit on a far smaller scale — he hasn’t seen a market emerge for newly engineered tape decks. And he’s fine with that.

“I’m not one of those people that’s like, ‘Why don’t they make good new tape players?’” he says. “No one needs to make it better. You’re still better off buying a refurbished one from the time when they made them.”

That’s where he steps in.

It’s easy to forget that when cassettes debuted in the mid-1960s, the technology was groundbreaking. Not only were the players far more portable than turntables but unlike records, tapes were resilient to being tossed about. Even more profoundly, cassettes democratized access to the act of recording itself since cassette technology required minimal infrastructure and cost.

“I think about how incredible it must have been for people to realize they could just put whatever they wanted onto a tape, dub it, give it to a friend,” says Richardson.

Entire genres of music, especially in the developing world, became far more accessible across borders. In some countries, big records are still released on cassette. “I have a Filipino release of Kanye West’s ‘College Dropout’ on tape,” Richardson says.

The constraints of the technology guided the listening experience. Because skipping songs on a player was a hassle, most people sat with cassette albums as a track-by-track, linear journey, the antithesis to the algorithmic, shuffle-centric playlists ubiquitous on today’s streaming platforms. It’s a pace that Richardson appreciates.

“I want things to be intentional and slow,” he says. “I don’t need them to be optimized.”

Born in the early 1990s, Richardson grew up in Santa Monica and the Pacific Palisades, where his mother’s home was lost in the L.A. wildfires last year. He’s just old enough to remember cassettes as a child: “My mom had books on tape like ‘Winnie the Pooh,’ but I wasn’t out buying tapes.” Fast forward to the mid-2010s and he was working at the now-defunct Touch Vinyl in West L.A. “Back in 2014, we started this little in-store tape label,” he explained. “Bands would come to play, and we’d duplicate 10 tapes and give them away or sell them.” Richardson slowly began collecting cassettes but after the store closed a few years later, he realized how hard it was to find people to service his tape players.

Finally, once the pandemic hit in 2020 and everyone was stuck at home, he decided to learn how to repair his gear by watching YouTube.“I was just fascinated by the videos, absorbing soldering techniques and tools you might need,” he said. With no formal engineering background, Richardson began collecting information online, perusing old manuals, learning through trial and error. “You just need to get your hands in there and be like, ‘Oh, OK, I see how this works,’ or maybe I don’t see how this works, and I’m just going to bang my head against the wall, and then a year later, try again.” His first successful repair was for his Teac CX-311, a compact stereo cassette player/recorder that he still owns. “It has some quirks but runs well.”

A few years later, Richardson’s girlfriend, Faith, suggested he start selling his players online via an Instagram account — jrmarket.radio — originally created for a short-lived internet station. Tim Mahoney, his childhood friend and a professional photographer, shot the units against a plain white backdrop, as if for an art catalog. A community of enthusiasts quickly found his account and Richardson began selling pieces online and via pop-ups. In 2024, the owners of vintage clothing store the Bearded Beagle invited him to take over the parking lot space behind their new location on Figueroa St. Opening a brick-and-mortar store hadn’t been his ambition but Richardson accepted the opportunity: “I never envisioned opening my own physical store. It’s hard enough to have a retail space in Los Angeles to sell something that’s very niche.”

Jr. Market — whose name is inspired by Japanese convenience stores known as “junior markets” — isn’t trying to appeal to audiophiles though Richardson does stock studio-quality recording decks. He primarily looks for players with appealing visual design, most of them made in Japan where Richardson has been traveling to since graduating high school. Through those trips, he’s learned where to source pristinely-kept gear, including his best-selling Corocasse: a bright red plastic cube of a radio/tape player, introduced by National in 1983. He also keeps an eye out for the unique Sanyo MR-QF4 from 1979, an elongated boombox with four speakers, designed to play either horizontally or flipped into a vertical tower.

The store also stocks a small selection of portable record players, including a Viktor PK-2, a whimsical, plastic-bodied three-in-one turntable, tape player and AM radio that looks like something designed by a modernist artist for Fisher-Price. That went to local author and historian Sam Sweet, who visited the store with no intention of buying anything and left with the Viktor, which now sits on his writing desk. “Spencer’s part of a grand tradition of workshop tinkerers and specialty mechanics,” Sweet says. “The refurbished devices he sells are as much a reflection of his ethos and expertise as they are treasures of the past.”

Last year, Imma Almourzaeva, an Echo Park art director, came to the store and purchased a massive 1979 Sony “Zilba’p” boombox, which is nearly 2 feet wide and over a foot tall, with wood veneer panels to boot. Almourzaeva, who grew up in Russia in the ‘90s, wanted a player that offered “the tactile feel of my childhood and bringing it back into my daily routine, something familiar, something warm.” The Zilba’p is the largest boombox Richardson has carried and Almourzaeva said, “It’s aesthetically a showstopper. Maybe I have a Napoleon complex because I’m pretty small too. It’s like ‘go big or go home’ for me.” She shared that she recently bought a Soviet-era boombox from Richardson for her brother for Christmas. “It turned out my mom grew up using the same brand of stereo,” Almourzaeva says. Richardson had told her that Soviet boomboxes are “very DIY, more funky and finicky.”

Refurbishment is one of Richardson’s specialties, including repairing customer units, each of them a puzzle he enjoys solving. No matter if a player is sparse or feature-packed, the simple act of playing a cassette creates a sense of calm and focus for him. “You’re not distracted, because it doesn’t do anything else,” he says. In a time where every “smart” device is marketed with dizzying arrays of features, that simplicity can feel downright revolutionary.

The post In a frenetic digital era, he’s helping Angelenos rediscover the classic cassette player appeared first on Los Angeles Times.