Uber is taking steps to enact stricter background checks, after a New York Times investigation in December revealed that the ride-hailing giant’s policies allowed for drivers with many types of criminal convictions, including violent felonies.

The company had barred drivers convicted of murder, sexual assault, kidnapping and terrorism. But in 22 states, The Times found, the company had approved people convicted of most other crimes — including violent felonies, child abuse, assault and stalking — so long as the convictions were at least seven years old.

Now, Uber is preparing to change those policies to bar people convicted of violent felonies, sexual offenses, and child or elder abuse and endangerment from driving for Uber, regardless of when those crimes occurred, according to people briefed on the matter. It is unclear when and how the changes will go into effect.

The company also is considering changing its policies for other offenses, including harassment, restraining order violations and weapons charges, which are generally allowed if the convictions are more than seven years old.

Uber declined to specifically comment on the changes. “Safety isn’t static, and our approach isn’t, either,” an Uber spokesman, Matt Kallman, said in a statement. “We listen, we learn, we speak with experts and we evolve as the world changes. We believe that’s the hallmark of a healthy, effective safety culture.” The company has long maintained that it is one of the safest ways to get around, with 99.9 percent of rides occurring without an incident of any kind.

Previously, Uber said the seven-year cutoff for felony convictions “strikes the right balance between protecting public safety and giving people with older criminal records a chance to work and rebuild their lives.”

A series of Times investigations revealed that Uber received a report of sexual assault or sexual misconduct in the United States almost every eight minutes on average between 2017 and 2022 — far more than what the company has publicly disclosed. Uber executives have long been aware of the extensiveness of sexual violence, The Times found, yet they repeatedly prioritized expanding their business over introducing stronger protections, such as automatic video recording.

The Times also found that the company allowed many drivers with records of complaints to keep driving — until passengers accused them of serious sexual assault.

Women who reported being sexually assaulted during Uber rides had said the company’s vetting practices put them in harm’s way. For example, in 2020, an Uber driver in San Diego with felony convictions for assault with a deadly weapon was reported to the police for using his fingers to forcibly penetrate a passenger’s vagina, then choking her and throwing her phone out the window when she tried to fight back.

The next year, an Uber driver in Tampa, Fla., with eight felony convictions, including for robbery with a firearm in 2002, was reported to the police for raping a passenger who had been out celebrating her 21st birthday. And in 2022, an Uber driver in Florida who was on parole after a decade in prison for two violent felonies was reported to the police for raping a passenger.

The changes to Uber’s background check policies come as the company faces increased scrutiny over its safety record from lawmakers, investors and others. In California, for instance, a proposed ballot initiative would make ride-hailing companies legally responsible for sexual misconduct and assault against drivers and passengers.

This year, in Virginia, lawmakers have introduced a pair of bills with stricter regulations for background checks, among other measures. “Drivers were slipping through the cracks,” said Lily Franklin, a House delegate who introduced one of the bills after reading the Times investigation. “There needs to be reform.” Uber has publicly supported both bills.

This month, a federal jury in Phoenix ordered Uber to pay $8.5 million to a passenger who said a driver had raped her. Uber argued that it was not responsible for the misconduct of drivers on its platform, whom it classifies as independent contractors, not employees. But the jury rejected that defense, providing a road map for more than 3,000 pending sexual assault and sexual misconduct lawsuits that accuse the company of systemic safety failures.

Uber, which fended off other claims in the case, including that it was negligent in its safety practices, has said it plans to appeal the verdict.

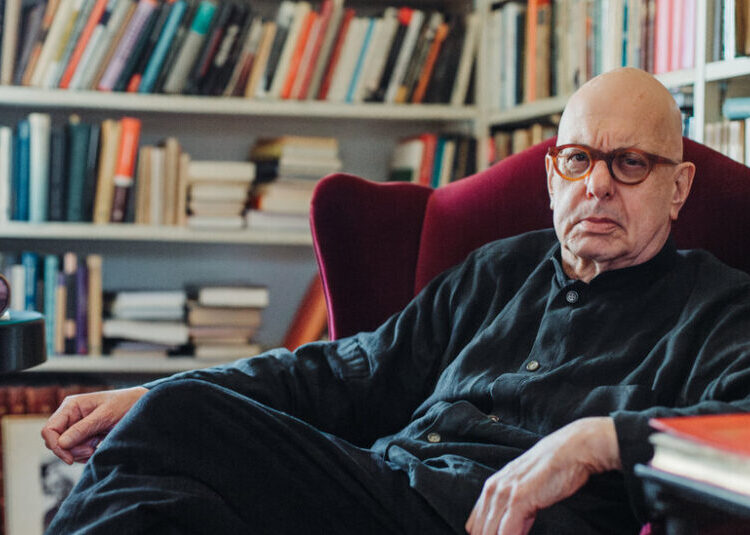

Emily Steel is an investigative reporter covering business for The Times. She has uncovered sexual misconduct at major companies and recently has focused on the ride-hailing industry.

The post Uber Moves to Enact Stricter Background Checks for Drivers appeared first on New York Times.