José van Dam, the Belgian opera star whose suave, silken voice, persuasive acting and steady work ethic made him one of the most esteemed bass-baritone singers of his era, died on Tuesday. He was 85.

The Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel, a training institute for young artists in Belgium, where he held the title of master in residence emeritus, confirmed the death in a statement. It did not say where he died or provide a cause.

Over a half-century career, Mr. van Dam delighted in portraying complex characters like Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Wagner’s Flying Dutchman. “You can sing it 200 or 300 times, yet you have to work every time to understand it,” he said in an interview with the music journalist Bruce Duffie in 1981.

He put great care into choosing the roles that were best suited to his voice at each juncture, as he gradually extended its range.

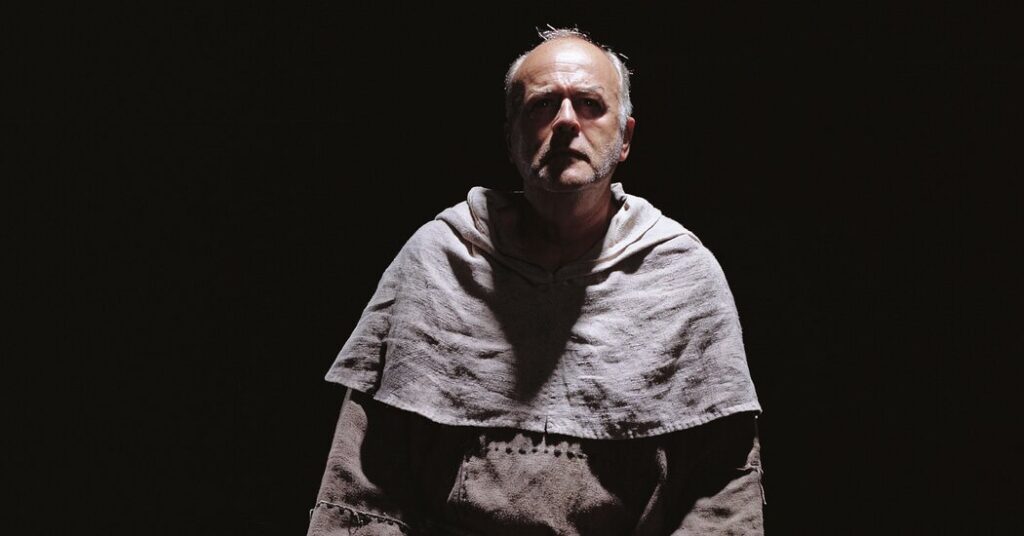

Such discipline did not impede Mr. van Dam from eventually taking on a broad repertoire that spanned the major operas of Mozart, Wagner, Verdi, Strauss, Gounod and Massenet, as well as less frequently performed works like Debussy’s “Pelléas et Mélisande,” Berg’s “Wozzeck” and Olivier Messiaen’s epic “St. François d’Assise,” whose title role Mr. van Dam created at its premiere in 1983.

He was, Peter G. Davis wrote in a review in The New York Times in 1981, “an elegant and immensely satisfying singer.”

While earlier in his career Mr. van Dam favored roles generally sung by true basses, such as Méphistophélès in Gounod’s “Faust” and Phillip II in Verdi’s “Don Carlos,” in his 50s and 60s he took on higher-lying baritone parts, like Scarpia in Puccini’s “Tosca.”

As he aged, Mr. Van Dam also shifted from the opera stage toward recitals, without losing his avid following or his voice’s polished, warm tone. His acting skills extended from the solemnly dramatic to the lightly comedic.

As he neared 60, Mr. van Dam was still capable of delivering standout performances in strenuous, lengthy roles like Messiaen’s St. François. Even in 2010, when he was 70, his “gift for vocal flair is still there,” the critic Simon Thompson wrote on MusicWeb International, as Mr. van Dam made his farewell to staged opera in the title role of Massenet’s Quixote adaptation “Don Quichotte” at La Monnaie in Brussels.

That he was able to sustain his voice into his later years brought him a certain pride, as he expressed it in an interview with La Scena Musicale.

“The most important thing,” he said, “is that the day I stop singing, people will say, ‘It’s too bad van Dam is no longer singing,’ instead of ‘It’s too bad van Dam continues to sing.’”

Joseph van Damme was born in Brussels on Aug. 25, 1940. His father was a carpenter, and his mother, who oversaw the home, encouraged her son to sing by playing records for him.

At 14, while still an alto, he auditioned for Frédéric Anspach, a singer and well-known pedagogue at the Brussels Conservatory; he was the only voice teacher Mr. van Dam ever had. Once his voice changed, he gained admission to the conservatory and distinguished himself by winning competitions. Without the school’s knowledge, he also briefly became a nightclub singer under the alias José Diamant.

He took a more permanent stage name, José van Dam, at 20, and made his debut in Liège as Don Basilio in Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville.” The same year, he signed a contract with the Paris Opera, but on the advice of Mr. Anspach, he initially turned down leading roles in favor of minor parts, as he developed his skills.

After four years in Paris, Mr. van Dam worked at the opera house in Geneva. Then he recorded Ravel’s “L’Heure Espagnole” with the conductor Lorin Maazel, who in 1968 invited Mr. van Dam to join the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. There, over the next eight years, he became an audience favorite in such roles as Leporello, the title character’s put-upon servant in “Don Giovanni,” and the toreador Escamillo in Bizet’s “Carmen,” which became a signature.

While in Berlin, Mr. van Dam also accepted other engagements, the most important of which was with the Berlin Philharmonic and its conductor, Herbert von Karajan, who hired Mr. van Dam to sing Don Fernando in Beethoven’s “Fidelio” at the Salzburg Easter Festival in 1971.

Thus began a long, fruitful relationship with Karajan, with whom Mr. van Dam made some of his many recordings. Although Karajan was notorious for pressing singers toward roles that risked straining their voices, he accepted Mr. van Dam’s cautious approach as well as his refusal to perform Don Pizarro, the villain in “Fidelio,” and the nobleman Telramund in Wagner’s “Lohengrin”; Mr. van Dam called them “crying parts.”

“I’m a singer, not a screamer,” he told Mr. Duffie in the 1981 interview. “It’s the conductor who must adjust.”

In 1973, Mr. van Dam scored another triumph as Figaro in Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” conducted by Georg Solti at the Paris Opera in a classic production by Giorgio Strehler that toured widely.

By the time Mr. van Dam made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1975 as Escamillo, he was considered the world’s leading exponent of that role.

“The range is treacherously wide, from solid bass to high baritone, and there is as much demand for soft, sensitive singing as for swagger and bluster,” John Rockwell of The Times wrote, adding that Mr. van Dam’s voice was up to the task.

“It is a large, mellow instrument,” Mr. Rockwell wrote, “able to modulate smoothly into soft singing. And his stage presence made the matador a fully commanding figure without falling into macho cheapness.”

In a 1979 review of “The Flying Dutchman” at the Met, Harold C. Schonberg wrote in The Times that Mr. van Dam was “a steady vocalist with a firm grip on the technical and expressive demands of the music.”

Nearly 20 years later, when he returned to Messiaen’s opera at the Salzburg Festival in 1998, Paul Griffiths wrote, also in The Times, that “Mr. van Dam, who has been St. Francis in every staged performance so far, sings with unswerving force.”

He added, “He sounds like a dark, low trumpet, always there to the full, always secure.”

As his career lengthened, Mr. van Dam kept to the plan he had set out while still in his 30s — to slowly cut back his opera performances in favor of song recitals.

The shift did not diminish his appeal. Reviewing his appearance at Carnegie Hall in 1995, Anthony Tommasini wrote in The Times that Mr. van Dam “barely made eye contact with his listeners; rather, he seemed lost to himself in a contemplative state and sang with an eloquence and affecting directness that compelled you to listen. I have rarely been part of a more riveted audience.”

Information about his survivors was not immediately available.

Mr. Van Dam appeared onscreen as Leporello in Joseph Losey’s acclaimed 1979 film version of “Don Giovanni.” In “The Music Teacher” (1988), which was nominated for an Oscar for best foreign-language film, he starred as an aging opera singer who takes on two promising students and counsels them to combine patience with a rigorous focus on technique.

In real life, Mr. van Dam began teaching at the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel in 2004, a relationship that continued until his retirement in 2023.

“Today, when someone has a beautiful voice,” he said in a 2000 interview, “they are discovered very quickly and pushed by the recording industry, and sometimes it comes too quickly for young singers. They forget that stars like Pavarotti and Domingo have taken years to get where they are now.”

The post José van Dam, Suave and Riveting Opera Star, Dies at 85 appeared first on New York Times.