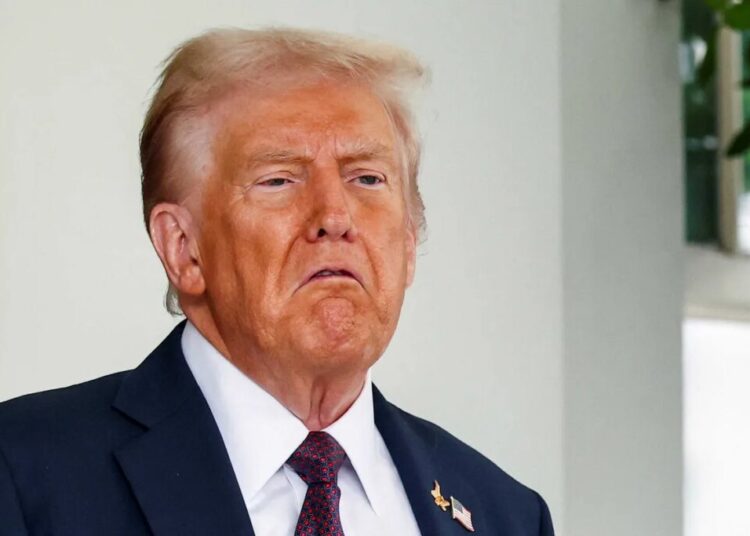

When President Harry S. Truman sought to add a balcony to White House in the 1940s, he faced opposition from the Commission of Fine Arts, which asserted that he was disfiguring a national monument.

Mr. Truman pushed past that advice, built the balcony and, for good measure, later fired members of the commission who opposed him.

Don’t expect any such fight this time.

As President Trump seeks to build a $400 million White House ballroom, he has taken several steps to eliminate any pocket of resistance to his plans from within his administration, stacking the boards and commissions tasked with overseeing the project with allies, including several people who work directly for him and some with no notable background in the arts.

Mr. Trump’s latest appointee to the Commission of Fine Arts, for instance, is his former receptionist Chamberlain Harris.

The panel provides advice on the project, but cannot block Mr. Trump.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation, an education and advocacy nonprofit based in Washington, objected to the new makeup of the panel this week, pointing out that the Commission of Fine Arts is supposed to include “experts in relevant disciplines, including art, architecture, landscape architecture and urban design.”

But there are no landscape architects on the panel, which the cultural landscape organization says is a “monumental deficit since the commissioners will be making decisions about one of the nation’s most important and visible designed landscapes.”

The White House has defended Mr. Trump’s picks, maintaining that they are more aligned with the president’s America First agenda.

“President Trump has an incredible eye and appreciation for the arts, and only selects the most talented people possible,” said Davis Ingle, a White House spokesman. “These individuals possess a wealth of experience that reflects the values of everyday Americans and President Trump’s vision to make America great again.”

Mr. Trump said on Wednesday that he planned to have the ballroom built and open to guests within a year and a half.

In October, Mr. Trump abruptly tore down one side of the White House, demolishing the entire East Wing, which contained the historical offices of the first lady.

The administration has been under legal pressure from historical preservationists to submit the new ballroom project to a formal review process. So far, the initial construction on the project has been allowed to proceed, though a judge recently expressed deep skepticism about the government’s case.

Here’s how the president is pushing through his project by remaking the panels that oversee construction in Washington:

Replacing the architect

Mr. Trump has faced much criticism that his plans for a White House ballroom are too large and that the building will dwarf the Executive Mansion and the West Wing.

The president’s first architect on the ballroom project, James C. McCrery II, presented him with several smaller approaches. But Mr. Trump kept pushing for a bigger project. The men disagreed over the ballooning size of the ballroom, and eventually Mr. McCrery agreed to take a step back as the main architect on the project.

He was replaced by Shalom Baranes, whose firm has been designing government buildings for decades and has collected awards for its commitment to historic preservation.

Remaking the Commission of Fine Arts

Mr. Trump also set out to remove other potential obstacles to his vision.

He fired the entire board of the Commission of Fine Arts last year, and began appointing replacements this year.

Among those appointed was Mr. McCrery, who has recused himself from discussing or voting on the project. Others include Ms. Harris, who works for Mr. Trump as the deputy director of Oval Office operations; Pamela Hughes Patenaude, who previously worked for Mr. Trump as the deputy secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development; and Mary Anne Carter, an ally of the White House chief of staff who serves as chairwoman of the National Endowment for the Arts.

The new chairman of the panel, Rodney Mims Cook Jr., has made clear that he views his job as ensuring that the president’s project can go forward.

“Our president has a very ambitious plan for the District of Columbia, as well as the world,” Mr. Cook said at the commission’s last meeting. “So we need to let the president do his job and, as best we can, keep his mind off of things like this, that we can keep him rolling, and do it as elegantly and beautifully as the American people deserve for generations and further centuries into the future.”

Remaking the National Capital Planning Commission

Mr. Trump has also assumed control of the leadership of the National Capital Planning Commission, although that panel also has representation from the D.C. government.

The National Capital Planning Commission must approve Mr. Trump’s plans before he can begin construction.

Mr. Trump has installed his former personal lawyer Will Scharf as the chairman of this panel. Mr. Scharf currently serves as assistant to the president and the White House staff secretary.

He is known for presenting Mr. Trump with executive orders for him to sign in the Oval Office.

Mr. Scharf made no objection when Mr. Trump abruptly tore down the East Wing to make way for the ballroom project. He maintained that his panel had no control over demolition, only new construction.

The National Capital Planning Commission has put the ballroom project on a fast track for final approval at its meeting next month.

Luke Broadwater covers the White House for The Times.

The post How Trump Is Making Sure His Ballroom Plans Sail Through appeared first on New York Times.