This year, the academy has added an Oscar for best casting. But what actually is good casting?

“Everyone’s going to have a different perspective when they sit down with their ballot,” Debra Zane, one of three governors of the casting branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, told me, adding, “for me, it’s about the storytelling, it’s about really making sure that this is all of one piece.”

Oscar voters are judging art, which means, to a certain extent, relying on personal taste. But over the years we have come to understand what academy members value in certain categories, for good or ill. With actors, the Oscars love transformation and big emotion. For costume design, extravagant gowns or ornately reconstructed period looks are favored over subtle character choices. And, of course, the film that the academy selects in an individual category might not be the same as the best picture winner.

“A movie could be great but you may not be stunned or wowed by the cast,” Zane said. “But then there might be a movie that maybe doesn’t, for whatever reason, check the boxes that might make you want to nominate it for best picture, but the cast is stunning and flawless.”

Often directors get the credit that should go to the casting department, with the conventional thinking being that they just call up celebrities. Instead, the casting directors I spoke with explained that their job requires a set of skills that can range from negotiating with top talent to selecting actors with breakout star potential to street casting — the act of finding nonprofessionals, often quite literally on the street.

“Any character who speaks in the screenplay will be cast by the casting director and sometimes characters who don’t speak, but who interact with one of the leads,” Zane said, “even if they have to be bumped into the street or something, that has to be someone who is tested out by the casting director. Because you have to be able to recommend someone who will not melt down on a set, who can do it multiple times, who can take direction.”

The “Marty Supreme” casting director Jennifer Venditti explained that casting directors may differ in their methods: “There’s people really great at putting lists together and doing deals and getting actors secured for movies, and then there’s other ones that are like this detective work, where they’re finding people and they’re curating and they’re putting combos of people together that you wouldn’t see.”

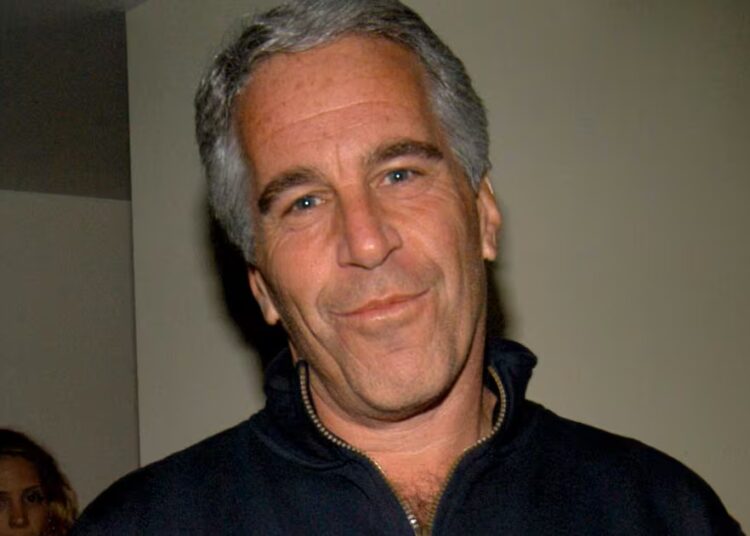

The nominees for the first casting Oscar are varied. “Hamnet,” about the death of Shakespeare’s son, features a host of critically acclaimed performers from Britain and Ireland, including a number of children. “Marty Supreme,” about table tennis in the 1950s, stars Timothée Chalamet but also a “Shark Tank” judge and a guy whose previous claim to fame was being a vocal Knicks fan. The bench of players on “One Battle After Another,” about revolutionaries on the run, went far deeper than just Leonardo DiCaprio, and included the rising star Chase Infiniti as well as Paul Grimstad, a professor at Yale. “Sinners,” a vampire tale centered in a Jim Crow-era juke joint, showcased veterans like Delroy Lindo as well as newcomers like Miles Caton, while “The Secret Agent,” the only international nominee, highlighted an array of performers from Brazil for its tale of a former professor in hiding during the country’s 1970s military dictatorship.

Of the 11 casting professionals I spoke to, most said that their best work was like putting together a puzzle. All of the actors have to fit naturally together and work in harmony to achieve the director’s vision.

“When I don’t notice the casting, that’s good casting,” Zane said.

For Francine Maisler, nominated for “Sinners,” the best casting isn’t about the number of stars. “I do think a great cast has newcomers,” she said, citing Caton, a musician who was touring with H.E.R. when he had the opportunity to audition for Preacher Boy. “I think it includes actors that, let’s say, you may not have been familiar with but I am.”

In Maisler’s case that included Jayme Lawson, who played Pearline in “Sinners.” She is a Juilliard graduate whom Maisler had auditioned for other projects before working on Ryan Coogler’s film.

The “One Battle After Another” casting director Cassandra Kulukundis joked that “I feel like I know more actors’ names than I do people in my life.”

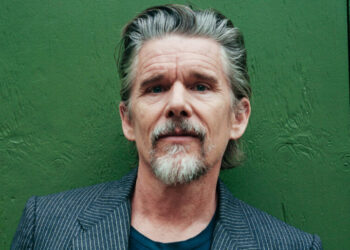

She has been working with Paul Thomas Anderson, the film’s director, since she was an intern on his first feature, “Hard Eight.” Now they collaborate via shorthand: He can send her a photo of a random person who resembles the character he imagines and she can respond with names of potential actors.

“My whole concept is: Make this world exist,” Kulukundis said. “So if it’s a famous person, you don’t want them to feel like this famous person. You want them to feel like they’re a regular person just living their life like you are.”

At the same time, she said, she’s thinking about how a film can grow on rewatch. “Like, you didn’t even notice that actor, but this next time you’re like, ‘Wow, he was so good,’” she said.

“One Battle After Another” includes Oscar winners like DiCaprio and nonprofessionals like James Raterman, a former special agent with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Investigations. Mixing working actors with untrained newbies is a specialty of Venditti’s, the “Marty Supreme” casting director who began her career casting unconventional models for fashion campaigns and editorials before transitioning to documentaries. She eventually linked up with the brothers Josh and Benny Safdie on their 2015 drama “Heaven Knows What,” which follows heroin addicts in New York. “Marty” reunited her with Josh, who directed the film solo.

“What makes casting interesting to me is the same feeling I have when I’m on the subway and I witness something, and I’m like, wow, who is that person?” she said.

Gabriel Domingues, who worked on “The Secret Agent,” said finding “expressive faces” is key to his job. Domingues knew that the director Kleber Mendonça Filho wanted to hire Wagner Moura, as the film’s star, and that he had a couple of other performers in mind when he recruited Domingues, but the casting director held an open call looking for people specifically from the northeast region of Brazil.

Domingues said that if you keep your eyes open to the variety of “human shapes, you succeed in casting because people are so interesting.”

The counter to that might be Nina Gold, a veteran British casting director who worked on “Hamnet” with Chloé Zhao, a director who had largely worked with nonprofessionals on her films “Nomadland” (2021) and “The Rider” (2018).

“This more kind of traditional actor route was not her background,” Gold said. “So she was very keen to collaborate and lean on me for my thoughts on that way of doing it.” Still, Gold focused on the idea of creating an “organic” family unit for Agnes and William Shakespeare, played by Jessie Buckley and Paul Mescal.

After the academy settled on a shortlist of 10 potential casting nominees in December, the casting directors participated in a “bake-off” in which they explained their work to other members of their branch, who were responsible for selecting the final nominees. The presentations — which will be available to the entire academy — consisted of prerecorded Q. and A.s and five-minute scene compilations.

“Hopefully the bake-off is educating people into, ‘Oh, there was a process, and it wasn’t just magical that all of those actors showed up onscreen,’” the “Wicked: For Good” casting director Bernard Telsey said.

And the processes varied greatly. For example, Venditti conducted interviews with hopefuls during auditions to get a sense of how they related to the characters they could play. Maisler combed Howard University and other schools to find Preacher Boy. And Gold said she saw probably hundreds of young actors for the title role of Hamnet, Will and Agnes’s doomed son.

Telsey, a former governor of the casting branch, said that he took the process into account while asking himself, “Did I think she was amazing in that movie? Did I think that will be a memorable performance 50 years from now? Those are the kind of things that should make you decide on how to vote.”

But Telsey also explained that he did not think of the casting prize as an award for the best ensemble, like the one handed out by the Screen Actors Guild.

“We’re recognizing the individual or the team that actually did the casting work,” he said, adding, “It’s not about the actors. We have the actors categories.”

Yes, casting directors are finding the right person to carry the weight of the movie, but they are also responsible for nearly every face you see onscreen, therefore creating the whole human environment of the film. In that way, perhaps the casting award is most akin to the one honoring production design. Just as the sets have to feel real, so do the people in them.

That’s that ineffable quality to good casting. For many, you know it when you see it.

“I feel like some of the traits of a good casting director can’t be taught really,” Venditti said. “It’s an incredible sense of intuition and knowing.”

The post With a New Oscar on the Line, How Do You Judge Casting? appeared first on New York Times.