The Rev. Jesse Jackson was always a standout in the way he dressed. But whom he dressed for, and why, are what made him exceptional.

By 2008, when he was an elder statesman in the fight for social justice tearily celebrating Barack Obama’s election, Mr. Jackson looked like most of the gray-haired men who’d entered the ring in the 1960s and continued to slug it out on behalf of the disenfranchised. He had become a man in a suit — or at least a sports jacket. But worn by him, establishment tailoring looked more like camouflage or perhaps a considered costume, rather than a uniform of convenience or acquiescence or a case of prideful dressing up.

From his arrival in the spotlight until his death Tuesday at 84, his attire always seemed to be telling a story about aspirations, for himself and for the country. Even when he was rising through the activist ranks during a time of respectability politics in the 1960s, he didn’t adhere to the prescribed, sober attire of the time. As a young man, he didn’t dress for gravitas; he dressed for urgent upheaval.

As the head of the Chicago-based Operation PUSH (later renamed the Rainbow PUSH Coalition), Mr. Jackson was photographed advocating equal economic opportunity wearing a dashiki. With its origins in West Africa, the tunic-like shirt was of a piece with Mr. Jackson’s pointed use of “African American” instead of “Black.”

Mr. Jackson’s dashiki laid claim to personal heritage and communal history — even if both were superficially defined. Even if the past was as wispy as a cloud, it was still present. It was real. The clothes confirmed it.

Clothes grounded Mr. Jackson’s enduring narrative of dignity, possibility and fairness. They were part of his personal mythmaking. They helped him tell the story of his accomplishments with a cinematic flair.

He was never quite a dandy. He didn’t go in for the sophisticated élan of political powerbroker Vernon Jordan. And he was not as flamboyant as the Rev. Al Sharpton during his early rabble-rousing days in New York. In his younger years, Mr. Jackson stood out from many of his peers — notably the late congressman John Lewis, another impatient young activist in the thrall of Martin Luther King Jr. When Mr. Lewis was in the public eye, he looked as if he was headed to a job interview at the local bank; Mr. Jackson dressed with a look-at-me flair.

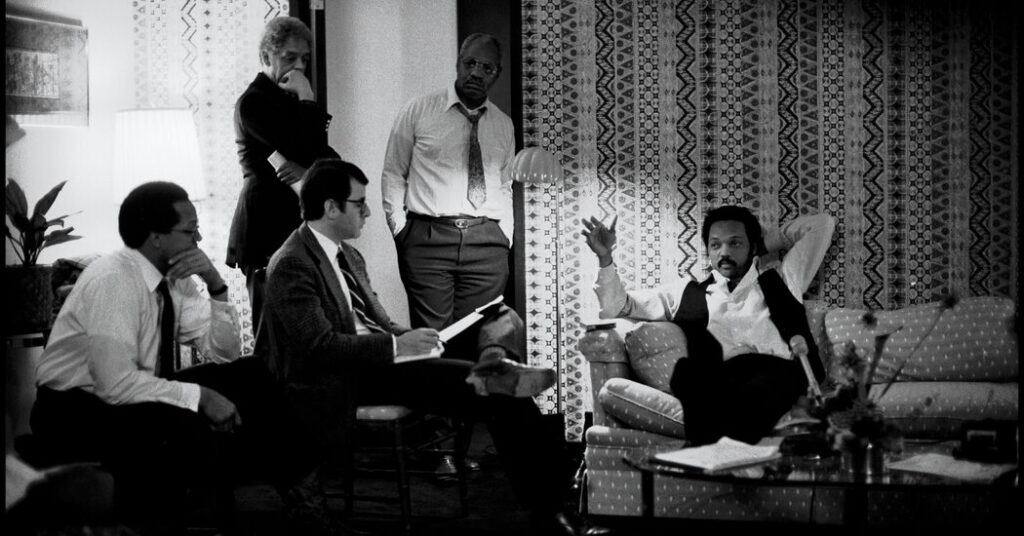

He was not a classic dresser; his clothes were overtly of their time. Over the years, he presented himself in a turtleneck, a dashiki, a three-piece suit, a leisure suit, in shirtsleeves with epaulets.

History associates those who were in the thick of the civil rights movement with suits and ties — a uniform they wore not just to demand respect but to show how much respect they already had for themselves. On April 4, 1968, standing on the second-floor catwalk of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis after an assassin’s bullet hit Dr. King, Mr. Jackson wore an olive turtleneck under his blazer. It was more formal than what the mostly white, middle-class hippies wore. He did not have the full privilege of being rakishly disheveled. His clothes didn’t convey the might of the burgeoning Black Panther Party. They were more relaxed than those of his elders, men who had come of age in the late 1940s and ’50s.

Clothes identified Mr. Jackson as in between. He was part of a transition. His clothing choices were exclamation points to his preacherly oratory. They were an emphatic expression of identity in protest of a history of erasure, a testimony to pride and ambition.

An individual but not yet free.

When he went off to Cuba in 1984 to facilitate the release of American and Cuban prisoners there, Mr. Jackson’s short-sleeved shirt with epaulets had the cut of a guayabera with hints of the military. It was not a uniform, and it wasn’t quite cultural appropriation. It spoke of clout and kinship. It was an example of aesthetic diplomacy. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright practiced it with her studied choice of brooches. Michelle Obama, when she was the first lady, engaged in aesthetic diplomacy when she considered geography, lineage and gender as she chose the designers for her state wardrobe. And it is regularly used by every politician who has ever walked onto a union factory floor, slipped off their suit jacket and rolled up their sleeves in a show of working-stiff solidarity.

When he fought his way onto the stage at the Democratic National Convention after his second run for the presidency, in 1988, he was a spokesman for America’s enduring optimism. He was dressed in a charcoal suit and a crisp white shirt. His tailored presence didn’t signify that he’d arrived at a long-sought lofty perch; rather, his clothes signaled that he had entered a new chapter of credibility. That journey began with Shirley Chisholm, who had run for president in 1972 wearing bold patterns, reveling in the fact that she stood out from her white, male colleagues. Sixteen years later, when Mr. Jackson won presidential primaries and caucuses in states including Michigan, South Carolina and Delaware, the word “symbolic” could no longer be so easily affixed to the campaign of a Black person seeking the country’s highest office.

One of the last times the public glimpsed Mr. Jackson was in March. He was in Selma, Alabama, to mark the anniversary of Bloody Sunday, the day in 1965 when voting rights activists assembled to walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge and were assaulted by law enforcement. He used a wheelchair and was swaddled against the chill in a black coat and scarf. But even surrounded by able-bodied men and women, he was not lost in the crowd. He was there in the middle of it all. Hunkered down. The event was a remembrance, but also a protest. He still had work to do to ensure the rights of all citizens.

The image of Mr. Jackson bundled against the cold was an admonition to disregard personal comfort, to disrupt the peace, to hunker down even now. It was the uniform that protesters wore in Minnesota when they stood in frigid weather to protest ICE. The clothes were not flamboyant. They were not a sop to respectability. But they painted a picture of the times, the people and the politics.

Robin Givhan is a Pulitzer Prize-winning fashion critic and a former senior critic at large for The Washington Post.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Jesse Jackson’s Wardrobe Was Also the Message appeared first on New York Times.