When border czar Tom Homan arrived in Minnesota in late January, he came to fix a host of problems for President Donald Trump. Indiscriminate and often violent immigration enforcement operations under Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino had sparked widespread public protests, and Trump’s approval ratings on his signature issue were tanking. Immigration agents had shot two people dead. Families were avoiding grocery stores and parents were keeping children home from school for fear of widespread document sweeps that were ensnaring legal immigrants and U.S. citizens.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

On the ground, Homan met with state and local officials to try to repair the shredded trust. Two weeks later, at a press conference to announce an end to the broad immigration crackdown in the state, he declared his visit a success, and suggested there was a plan to ensure immigration operations there going forward would be “targeted” and focused on “national security threats and public safety threats.”

But what Homan said immediately after that exposed the contradiction at the heart of Trump’s immigration policy at this charged moment.

“For those who are not a national security threat or public safety risk, you are not exempt from immigration enforcement actions,” Homan said. “If you’re in the country illegally, you are not off the table.”

Trump campaigned in 2024 on overseeing “the largest deportation in the history of our country.” He has frequently said that his Administration is deporting “the worst of the worst criminals.” Yet those two goals have proven to be incompatible.

In reality, tens of thousands of people with no criminal record or pending criminal charges have been being pulled off the streets by immigration agents and put into detention centers. If that pattern were to stop, the Trump Administration’s deportation stats would likely plummet.

“The apprehension of criminals moves more slowly than everyone else,” says John Sandweg, former acting director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement during the Obama administration.

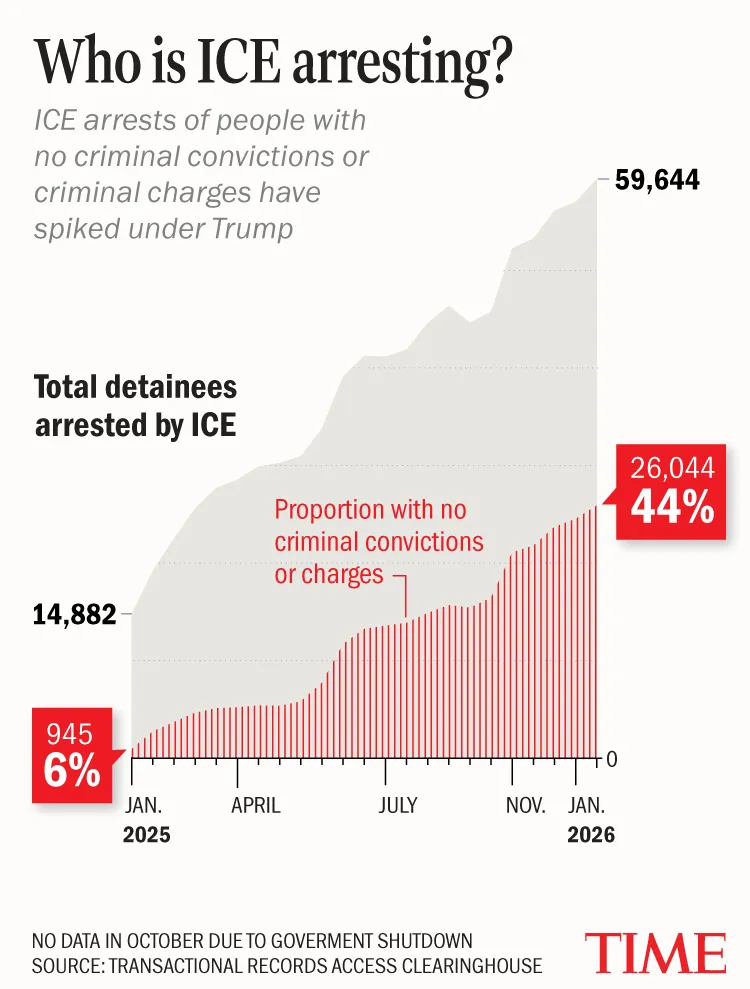

The data illustrates Trump’s commitment to mass deportations. The number of people arrested and detained by ICE who have no criminal convictions or pending charges has skyrocketed from 945, or 6% of all arrests, last January, to 26,044, or 44%, last month, according to data published by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. That spike reflects a dramatic transformation in how the country’s immigration system treats people who are in the country unlawfully, but have no criminal convictions or pending criminal charges.

Under the Biden Administration, immigration officers prioritized detaining people who had criminal convictions, posed a public safety threat, or had recently crossed the border into the U.S. But Trump wiped away those priorities in his first few weeks back in office. Immigration agents were free to be more indiscriminate in the undocumented people they arrested.

Doing broad sweeps was the only way that Trump was going to achieve his goals of boosting deportation figures. “Canvas-style operations, worksite operations, produce a much lower percentage of criminals than targeted operations,” Sandweg says.

Inside the White House, officials insist that Trump’s orders are intended to target and arrest those who have committed crimes while also deporting thousands of additional people who don’t have authorization to be in the U.S. “The President’s entire team, including Border Czar Tom Homan and Secretary Noem, are on the same page when it comes to implementing his agenda—which has always focused on prioritizing the worst of the worst criminal illegal aliens—and the successful deportations and historically secure border proves that.” says White House deputy press secretary Abigail Jackson.

“As always, anyone in the country illegally is eligible to be deported,” adds Jackson. “President Trump is keeping his promise to carry out the largest mass deportation operation in history.”

The push for mass deportations is being fueled by the decision by Republicans in Congress to allocate an additional $75 billion to ICE, making it the nation’s highest funded law enforcement agency. The agency has hired thousands of new agents, and is currently working to spend billions of dollars to significantly expand its detention space to hold more people the agency wants to deport. That funding was appropriated in a way that lets the agency spend it through the end of Trump’s term, says Dominik Lett, an expert on the U.S. budget at the Cato Institute. “It’s a bucket of money that is being drawn down with very little oversight from Congress,” says Lett.

Over the weekend, the Department of Homeland Security’s funding ran out as Democrats demanded installing several new guardrails on immigration agents. But while Transportation Security Agency workers at the nation’s airports and members of the Coast Guard may soon have to work without pay, ICE’s enormous financial cushion means it is expected to face far less impact to its ongoing operations.

Yet Democrats are expected to continue pressing the issue, seeing the public on their side in the aftermath of the shooting deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti and other actions by immigration agents in Minneapolis that drew national attention. Six in ten Americans think Trump has gone too far in his immigration crackdown, according to polling from the AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research at the University of Chicago. Sixty percent of the public now has unfavorable views of ICE, compared with 37% of Americans who viewed the agency unfavorably in 2018.

The post Trump’s Vows to Target ‘Worst of the Worst’ Collide With a Mass Deportation Reality appeared first on TIME.