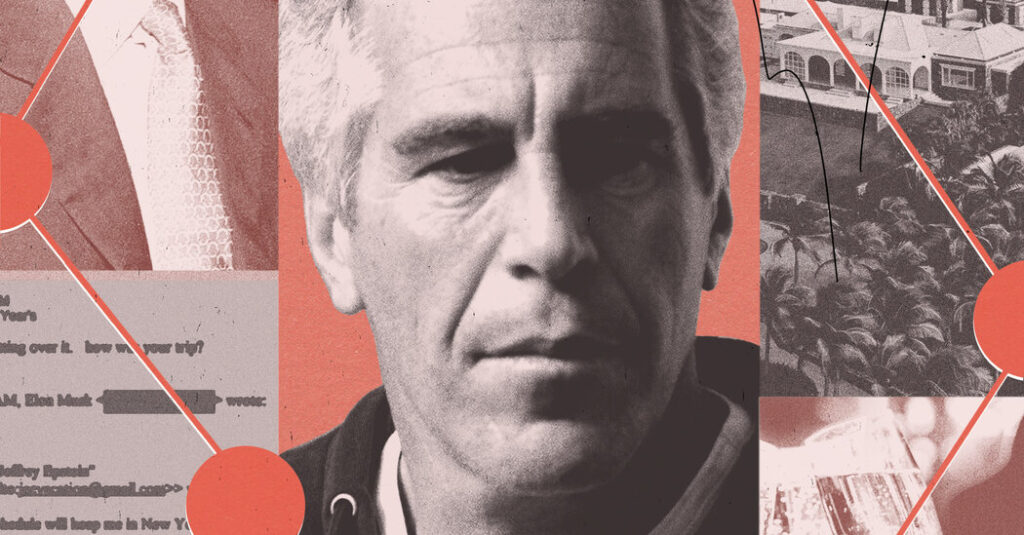

When Jeffrey Epstein said “massage” in the years after he got out of jail in 2009, what did his friends and associates think he meant? Epstein had been convicted in a Florida court of sex crimes with minors in 2008. His method, reported in The New York Times at the time, had been to recruit girls as young as 14 to his home and persuade them to undress and massage him. Then he would force them to have sex and paid them cash.

He was charged with sex crimes again in 2018, this time by the federal government, which accused him of trafficking underage girls in the early 2000s. If he committed crimes in the years between 2009 and his death in a Manhattan jail cell while awaiting federal trial in 2019, he was not charged with them. But the Epstein files show that, during that decade, he was both rebuilding and curating his vast, elite social network, while also looking at plans for a new massage room on his private island of Little St. James and choosing marble for his massage room in New York.

At the same time, he was vetting young women from all over the world for their sexual attractiveness, ranking their attributes, soliciting sex and enlisting them into his service. “Very beautiful, fresh,” one scout wrote to Epstein in 2011 of a 21-year-old woman, about 5 feet 8 inches tall. “Nice girl, but almost no English at all,” the same scout wrote of another, who was 22.

That Epstein was a registered sex offender in New York and Florida was a matter of record. That he usually traveled with an entourage of “girls” — in his correspondence he also called them “assistants” or “students” — was common knowledge. Richard Branson called this entourage Epstein’s “harem.” “As long as you bring your harem!” Branson wrote in 2013. (A representative for Branson has said that he met with Epstein only a few times, in business settings, and that he saw him only with adult women. Branson considers Epstein’s actions “abhorrent,” the representative said.)

At least some of Epstein’s friends knew what he meant when he said “massage.” In 2010, in an email to Boris Nikolic, then the science adviser to the Gates Foundation, Epstein said he was finishing one.

“With happy ending I hope,” Nikolic responded, punctuating his note with a winking emoji. (Nikolic did not respond to a request for comment.)

“I’m too impatient, happy beginning,” Epstein replied, with characteristically haphazard punctuation.

The emails also show Epstein organizing massages for friends and connecting friends with women as favors or gifts. When in 2017 Deepak Chopra complained of a “crazy” day, Epstein replied, “I’m in Florida, but would like to send two girls.” (“I am deeply saddened by the suffering of the victims in this case,” wrote Chopra in a statement earlier this month.)

Kathryn Ruemmler, former White House counsel under President Obama, implicitly acknowledged she knew the difference between a massage and what Epstein engaged in, referring to it in an email as “your kind of massage.” She also knew Epstein’s history. He sometimes sought her legal advice, and in 2015, she pointed out to him, clearly, that a minor “could not legally consent to engaging in prostitution.” But in 2017 Epstein was accompanying her as she looked at apartments.

On Feb. 3, she said through a representative, “I had no knowledge of any ongoing criminal conduct on his part, and I did not know him as the monster he has been revealed to be.” On Thursday, she resigned from Goldman Sachs, where she was the firm’s top lawyer.

Even in a world where a president can receive oral sex from an intern, lie about it, get impeached and remain in office; where a candidate for president can be heard saying that he can grab women “by the pussy” without fear of reprisal and get elected, twice, Epstein’s social prominence is astonishing. It shows how a group can collude with dark secrets if they’re sufficiently ambiguous and serve their interests. At least one friend warned Epstein of possible reputational damage from his behavior with women. His conviction had been public, after all, and “could be interpreted — indeed was — as a powerful man taking advantage of powerless young women,” the friend wrote. (The person’s name was redacted.)

What’s most shocking is that no one said anything.

How is it that “the girls,” as Epstein called them — their presence, their provenance, their role — failed to raise misgivings above the quietest whisper among the super-powerful men and women who dined at Epstein’s table? The list of boldface names availing themselves of Epstein’s hospitality is by now familiar. Elon Musk. Steve Bannon. Peter Attia. Guests like these exist within their own galaxies of assistants, advisers and hangers on. Is it possible that no one raised questions about Epstein’s treatment of women beyond a certain coy or coded admiration for what they saw as his extravagant taste?

“His lifestyle is very different and kind of intriguing although it would not work for me,” Gates wrote to colleagues in 2011 after a visit with Epstein. (Gates has called his relationship with Epstein a “big mistake” and denied Epstein’s claim in a draft email that Gates engaged in extramarital sex.)

In an interview with Die Zeit on Feb. 12, the cognitive scientist Joscha Bach acknowledged that Epstein’s “relationship to women in his environment, especially some of his employees, seemed unfriendly at times and disrespectful.” In a separate email to The New York Times, Bach added that he “had some conversations” with Epstein’s assistants “in which I inquired about their well being.” He added: “Nothing they told me or what I observed gave reason for concern that anything coercive or illegal could be going on.”

Tessa West, a professor of social psychology at New York University, describes the collective silence around Epstein and his “girls” as “willful inaction.” Even if the guests at Epstein’s table were not engaging in illegal or harmful behavior, some had to have seen red flags, and “they’re doing nothing about it. They’re not saying anything. They’re not discouraging it,” West said. Given what she knows about gender dynamics in her profession, academia, “I am zero surprised by any of this,” she said. Scientists like West offer clues to why and how Epstein’s world functioned to protect him.

Social psychologists describe Epstein’s world as an “in group” upgraded by “optimal distinctiveness.” Distinctiveness conveys exclusiveness, and Epstein was the man at the velvet rope, choosing those who were “in.” Guests at his table had to be interesting, vogue-ish, powerful or useful enough. “The girls” were ranked on a scale. “10 ass,” he said of a woman whom he connected with Steve Tisch, chairman of the New York Giants. (Tisch has said he regretted what he said was his brief relationship with Epstein and that the women they had discussed were adults.)

The exclusivity had a multiplying effect. The more top notch the company, the more people wanted in. And Epstein had a lot to offer, West pointed out. “Soft power, opportunity, financial opportunity, social connection,” she said — and, crucially, for the professors and university presidents knocking at his door, “money in a world where academics don’t have any.” Some of “the girls” saw Epstein as an opportunity, too. He sent them to Frédéric Fekkai for haircuts and referred them to plastic surgeons. “He will send you to his partner that takes fat from your ass and puts it in your breasts,” he wrote to one. He sent them to the doctor and seems to have paid for school — including, apparently, massage lessons.

The gatherings, the properties, the amenities — all were designed to seduce and astonish. At the compound on Little St. James, the food was “better than any we’ve had at the Ritz,” Ellis Rubenstein, then the president of the New York Academy of Sciences, wrote to a friend. He went there with his kids. (Rubenstein did not respond to requests for comment.)

The French orchestral conductor Frederic Chaslin was entranced by a visit to Epstein’s Santa Fe ranch. “There is something totally voluptuous about all that I saw, I was feeling drunk from the beginning to the end without a drop of alcohol. Like being inside a work of art,” he wrote to Epstein in a thank-you note.

Earlier this month, Chaslin issued a statement. Any implication that he did wrong is “based on isolated sentences, out of context and loaded with intentions they never had,” he said. “I formally refute these hints.”

“The girls” were in attendance at dinner parties and on the plane. Lesley Groff, Epstein’s executive assistant, booked multiple hotel rooms when Epstein traveled. “Regarding the 2 bedroom suite… do the bedrooms each have king size beds?” she asked Thomas Pritzker’s assistant. Pritzker is the executive chairman of Hyatt Hotels Corporation, and he apparently helped Epstein with rooms. “2 double beds?” Groff asked. “Or what is the arrangement there?” (On Tuesday, Pritzker resigned as Hyatt’s executive chairman, saying he “exercised terrible judgment” in staying in contact with Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell.)

Self-interest would have prompted his guests and visitors to look away, West said. And Epstein’s coded, euphemistic language gave them cover. Unless incontrovertible evidence of a renewed sex trafficking operation was “literally in your face,” the provenance of “the girls” and their role could have been downgraded to an uneasy feeling or a rumor, West explained.

“Any time there is sufficient ambiguity in the behavior of a person, we are motivated to see it in a way that benefits us,” she explained.

Perhaps that is why the paleontologist Jack Horner, the winner of the MacArthur Foundation’s so-called “genius” fellowship, could assert in his apology earlier this month that when he visited Epstein at his Santa Fe ranch in 2012 and was introduced to four “college students, two of whom claimed to be adept in genetics,” he saw “nothing weird, inappropriate, or out of the ordinary.” He added: “I now understand the students may have been victims of Epstein, and I deeply regret that I did not realize this.”

In his thank-you note at the time, Horner wrote, “I had a great time, especially spending time with you and the girls, and seeing your Cretaceous sediments and the old railroad.” He signed off, “please give all the girls my very best wishes, and to you, whom I envy.”

In 2012, experiments by the Dutch social psychologist Gerben van Kleef demonstrated how rule-breakers amass power. Scientists had already shown that powerful people are likelier than others to violate norms, as he wrote in his paper: to interrupt, to eat with their mouths open, to cheat, to lie in negotiations, to break traffic laws, to lack empathy, to treat others as objects, to ignore suffering and to sexually harass lower-status women. People who drop cigarette ash on the floor or put their feet on their desks are perceived by others as powerful because their defiant actions signal that they can seem to do what they want, despite the constraints.

Van Kleef hypothesized that social groups cede power to transgressors only when the transgression benefits them. In his experiments, he found that a man who helps himself uninvited to a stranger’s coffee thermos amasses power when he shares the stolen coffee with others. If he steals the coffee and keeps it for himself, he does not. Scientists cannot study harmful norm violations such as sexual aggression, Van Kleef wrote.

Clearly, Epstein relished his transgressor role. He loved taking extreme, unpopular stances on political and cultural topics. He made arguments about gender roles, physical beauty and intelligence from a social Darwinist view, making such comments as “ugly is usually unhealthy, deformities signal disease.” His friends seemed to credit him with intellectual honesty.

“You’re a genius,” wrote Martin Nowak, a mathematician at Harvard, repeatedly. (Nowak did not respond to a request for comment.) In an email exchange with Bach, the cognitive scientist, Epstein reflects, inscrutably, on eugenics — questions of innate abilities of women and Black people — and seems to propose the euthanasia of the elderly.

“I find your ‘political incorrectness’ very fascinating,” Bach responded. “In the beginning, I thought it is a form of costly signaling, but now I think you are simply entirely unconstrained in your thoughts. How did you manage in your youth?” (In his interview in Die Zeit, Bach was asked whether he had doubts about Epstein, given his prior crimes. Bach said he did, and consulted with “a significant circle of eminent scientists.” He said, “Everyone I talked to insisted that Epstein had changed his ways after his conviction and no longer broke any laws. And that he had done great services to science, despite his irrecoverable public reputation.”)

Epstein’s open misogyny seemed to enable others. The files show him discussing the size and shape of women’s breasts with Tancredi Marchiolo, the London-based hedge fund manager. After Marchiolo had sex with someone he called Arizona Muse, he reached out to Epstein to discuss. “A bit old, 25, the tits look like a 70 yr-old sagging woman that had them reduced,” Marchiolo wrote. Also, Marchiolo complained, she had a child. Once a woman has given birth, “the party’s over,” he wrote, in Italian. (Marchiolo did not respond to a request for comment.)

Secrecy encircled all of this talk, a dynamic that Peter Attia, the longevity influencer, described in his recent apology for joining Epstein’s misogynist banter. In 2016, Attia wrote a fawning email to Epstein. “The life you lead is so outrageous and yet I cannot tell a soul,” he wrote, while also joking that “pussy is, indeed, low carb.” Now he calls that message “juvenile,” and defends himself as having been naïve and sucked into a world that felt strange and exciting.

“He lived in the largest home in all of Manhattan, owned a Boeing 727,” Attia wrote. “I treated that access as something to be quiet about rather than discussed freely with others.”

The secrecy worked like glue, binding Epstein’s associates closer to him, and Epstein himself enforced it. In emails to his powerful friends, which had threatening undertones, he alluded to shared confidences and referred to them as a mutual debt.

He reprimanded women who left sex toys in full view and acquaintances for violating his code of decorum. When the global marketer Ian Osborne apparently made the mistake of reaching out directly to Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s office to invite him to an Epstein-hosted event, Epstein reprimanded him. “Unless necessary I always prefer that the fewer people that know the better so your email to his office people was concerning,” he wrote. “If Michael in any way feels awkward, tell me.” (“I wholeheartedly regret that I ever met, or had any association whatsoever with, Epstein,” Osborne said earlier this month.)

Secrets “create a boundary between who’s in and who’s out,” said Michael Slepian, a social psychologist at Columbia University, and they enhance insiders’ sense of being chosen. A shared secret, Slepian continued, has a paradoxical effect. “It actually makes it harder to hide. But it makes it easier to live with.”

The banality of so many of the emails is striking. Can’t make 1 p.m., how about 1:30? Won’t be in town after all. Flying to Paris, to the Caribbean, to Palm Beach. Here are the flight manifests, the tickets to Davos, the screening, the benefit. Here’s the guest list, the menu. Mort Zuckerman is vegan. Soon-Yi Previn is on her way to Pilates. Sorry to cancel. Can we reschedule?

Kurt Gray, a moral philosopher at Ohio State, described how people might find themselves complicit in unimaginable harm and collective silence. A focus on day-to-day details can serve to distance people from what’s before them. “I think they’re just like, ‘Yeah. I’m going to do a little logistics. I’m going to get there. I need support for my research from a hang with this fun guy who says interesting things.’”

Then people find themselves at Epstein’s dinner table, “and you want to be part of this group, and be this easy dude on this island. You want to be included. You don’t want to be rejected.” Gray continues, “And you’re just not thinking about these women or how they got there or their plight or their humanity. It’s this kind of myopia.”

Lisa Miller is a Times reporter who writes about the personal and cultural struggle to attain good health.

The post The Price of Admission to Epstein’s World: Silence appeared first on New York Times.