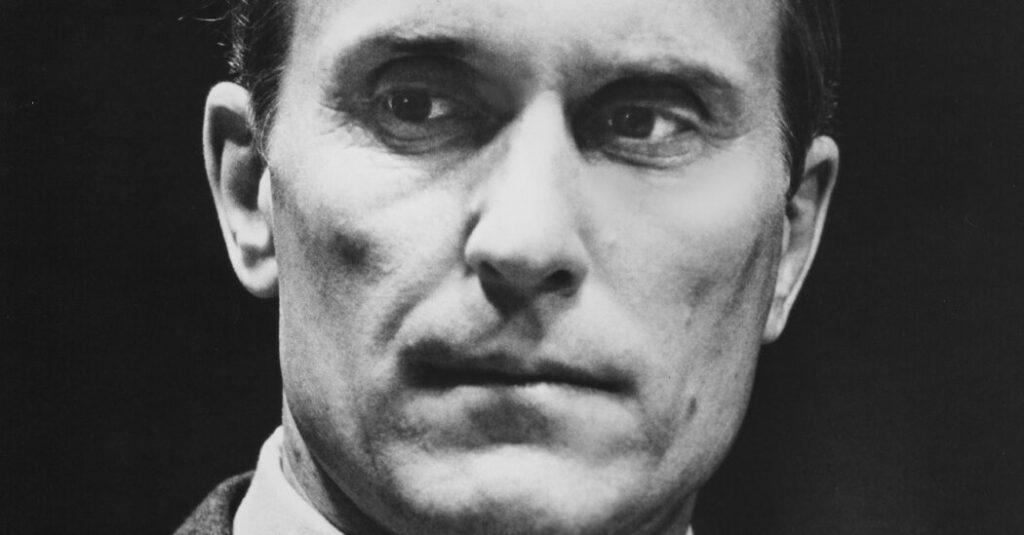

The first time you watch the opening of Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather,” you may not notice the pale man with the hawklike stillness seated quietly in the room. There are so many other things to look at in this seismic opener, including James Caan’s Sonny as he waits restlessly in the background and Marlon Brando’s Don Corleone, who’s seated behind a desk in pooling shadow and holding a cat as he listens to a man ask him to murder someone. The Don declines to do so though promises to handle matters, and then both men stand.

As soon as the petitioner leaves, the pale man suddenly and silently takes his place before the Godfather, materializing from the inky black like an apparition. For the rest of this scene, these two men remain close to each other, the darkness enveloping them like a shroud. Don Corleone is facing the camera while the pale man’s face remains largely obscured. You can’t quite make him out, and he doesn’t say a word as the Godfather speaks, adding to his strange mystery. Yet by the time the scene ends, so much has already been expressed, including the men’s intimacy and the unwavering intensity of the pale man’s supplication. This is a man, you understand, who doesn’t just serve power but also helps make it happen.

In a sense, the same was true of Robert Duvall, who died on Sunday at 95. Over his decades-long career, he sometimes took the lead, as in the 1980 drama “The Great Santini,” but was also a brilliant team player. By the time he appeared as the mysterious pale man, a.k.a. Tom Hagen in “The Godfather” — the Don’s future consigliere — Duvall was part of a group of Coppola’s close collaborators who over the years and in different movies would help the filmmaker realize his ambitions. The actor and director made a number of movies together, starting with “The Rain People” (1969), a moving, loosely plotted drama about a pregnant woman (Shirley Knight) who flees her middle-class life by hitting the road. Along the way, she meets two oppositional men, one poignantly wounded (Caan), the other menacingly so (Duvall).

Duvall plays a patrolman, Gordon, who stops the woman, Natalie, for speeding on an atmospherically lonely highway. Wearing sunglasses, the cop is crisply officious at first, but after some banter about her marital status she seems to understand that there’s something else in his attentions. Duvall excelled at tightly wound characters, and though he doesn’t tip what Gordon thinks, you can intuit the danger in the man. Even so, before long, he and Natalie are in a diner, then in bed. Duvall didn’t play romantic roles often, yet while he’s convincingly attractive here, Gordon remains almost imperceptibly on edge. You can see volatility in his darting eyes, hear the impatience in his words. The film ends badly for all of the characters, but by that time all of the actors — Duvall included — are seared into your memory.

I imagine that at that point, Duvall had already quietly bored into the consciousness of a lot of moviegoers who probably didn’t even know the name of the actor who played Boo Radley in Robert Mulligan’s 1963 film version of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” A silent shut-in, Boo is a figure of intense speculation among the local children, a neighborhood boogeyman who’s said to be a near-giant — six and a half feet tall — and “eats raw squirrels and all the cats he can catch.” By the time Boo appears onscreen near the end of the movie, he has saved two children from death and taken refuge in their house behind a door, standing stock-still with a face that the film’s young heroine, Scout, reads with fast-dawning adult recognition — a face that Duvall fills with a haunting mix of wariness, crushing isolation and childish incomprehension.

Boo Radley’s role in the story is small yet pivotal, and it’s made all the more unforgettable by Duvall’s tamped-down force. It was his first film role, and it initiated a career that built momentum gradually but insistently in films from directors as different as Robert Altman (“Countdown,” 1968) and George Lucas (“THX 1138,” 1971). Although Duvall sometimes had top billing or thereabouts, and certainly could feel like a supernova, he invariably seemed more like a supporting actor than a star. Some of this was a matter of intransigent Hollywood ideas about male beauty that continued even as Old Hollywood gave way to New. Duvall was certainly nice-looking, but his receding hairline and the way his skin seemed to stretch tightly, almost wincingly, across his facial bones doubtless mattered to those cutting the checks.

Duvall’s ability to disappear into roles was another factor in the trajectory of his career, and I imagine so were his native intensity and apparent lack of interest in cozying up to the audience. He never seemed to ask for its love even when the movies did, as in “The Great Santini,” in which he plays a tough, hard-drinking family man and Marine, Lt. Col. Bull Meechum. In its most famous scene, a driveway basketball match turns into a harrowing battle of wills when Meechum grows enraged that his eldest son is besting him. The father responds first by threatening to beat his wife, and then begins to repeatedly bounce the basketball off the son’s head, violence that Duvall plays with such hard, single-minded focus — and some unnervingly weird barking laughs — that even the tears Meechum sheds later leave you cold.

Duvall had the kind of long, storied career that was possible in an earlier movie era, one that helped define New Hollywood and also outlasted it. He did his share of paycheck jobs, popping up in blockbuster nonsense and forgettable independent films. After winning an overdue Oscar for “Tender Mercies” (1983), he went on to write and direct several appropriately idiosyncratic films: “The Apostle” (1997), in which he played a preacher turned murderer, and the delightfully eccentric “Assassination Tango” (2003), in which he played John, a tango-loving hit man whose story begins in Coney Island and improbably leads to Buenos Aires. There, while on the job, John learns the tango, which may not be an intentional metaphor but nevertheless comes across as one about doing the job while also following your bliss.

By that point, the role of Tom Hagen was long behind Duvall. He had appeared in the first two “Godfather” films but declined to appear in the third because the production wouldn’t pay him as much as Al Pacino. It’s understandable, and his refusal — along with the pride that edges it — recalls an early scene in “Assassination Tango” when John gets dressed to go out. He is a strange, complicated cat who’s at once a loving married family man and a dangerous hired gun, and he seems as capable of inhabiting as many roles as the actor playing him. The night in question, he is about to pull off a sanguineous job with his customary finesse. First, though, he puts on a sharp black hat and dark clothes and primps in front of a mirror, dabbing lotion on his cheeks. And then John carefully smooths the wrinkles on his throat, an unmistakably vulnerable moment that Duvall holds on for a few seconds with memorable, sublimely knowing grace.

Manohla Dargis is the chief film critic for The Times.

The post Robert Duvall Seared Himself Into Our Memories Even When He Wasn’t the Star appeared first on New York Times.