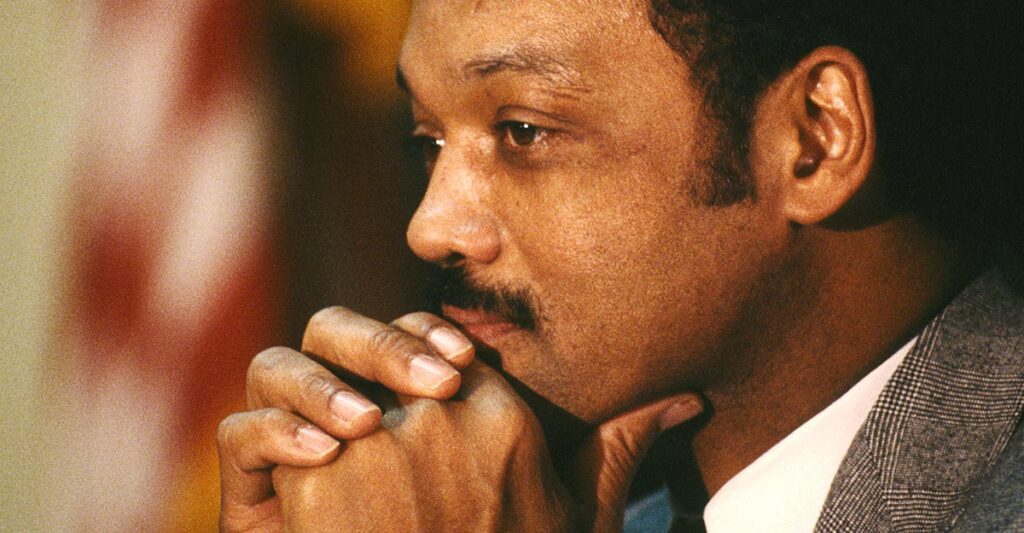

When I was growing up in Washington, D.C., in the 1990s, many businesses proudly kept in their windows signs from Jesse Jackson’s 1984 and ’88 presidential runs. He was a revered figure, someone people in D.C. were deeply thankful for.

“Nothing will ever again be what it was before,” the writer James Baldwin said after Jackson’s ’84 Democratic National Convention speech.

“It changes the way the boy on the street and the boy on Death Row and his mother and his father and his sweetheart and his sister think about themselves. It indicates that one is not entirely at the mercy of the assumptions of this Republic, of what they have said you are, that this is not necessarily who and what you are. And no one will ever forget this moment, no matter what happens now.”

Yet when you turned on the television, you saw another Jesse Jackson. This Jesse Jackson was a dangerous man, a radical, a demagogue, someone who thrived off fomenting racial division. To the people around me, Jackson—the reverend and civil-rights leader—was a hero. But to the people I saw discussing the news on television, he was both an incendiary agitator and a ridiculous, almost comic, figure. The subtext of all this commentary was that Black Americans would make more progress if their leaders were not so flawed. Barack Obama put the lie to this argument; squeaky-clean by personal-conduct standards, all he did was drive the same people who hated Jackson more insane.

“Have you ever noticed how all composite pictures of wanted criminals resemble Jesse Jackson?” the right-wing radio host Rush Limbaugh mused in the 1990s. His opinions on Obama were no less unhinged.

[Ali Breland: The Epstein emails show how the powerful talk about race]

“There has developed among many, for sure, a kind of attitudinal air-barrier of cynicism” around Jackson, Marshall Frady, a journalist and the author of Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage of Jesse Jackson, once said. “Part of it is, no doubt, a reflection of the abiding, if not steadily deepening, racial schism in the country since the ’60s.” Jackson was one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s youngest lieutenants; he came of age when many considered racial injustice history, an issue the country had already dealt with. He reminded Americans that King’s dream had not yet come, and that created for him enemies. In hindsight, it seems strange that people would assume that the effects of centuries of slavery and segregation would be entirely wiped away in fewer than two decades. Jackson had grown up in poverty in the shadow of Jim Crow segregation; it must have seemed even more absurd to him.

It was common for right-wingers to refer to him as a “race pimp” or “race hustler.” He did himself no favors when, in 1984, he used an anti-Jewish slur—calling New York City “hymietown”—in a conversation overheard by a reporter. Jackson apologized for the ugly remark, but it followed him for the rest of his life—in mainstream media, the incident was practically a second appellation, right after “the Reverend.” In 1989, the Fox News founder Roger Ailes, then an adviser to Rudy Giuliani’s mayoral campaign, placed an ad in a Yiddish newspaper with a photo of Giuliani’s rival David Dinkins next to Jackson—the two were friends. The clear implication was that Dinkins was an anti-Semite, just like Jackson. In this way, Jackson became an easy shorthand propagandists could use to terrify white people into voting Republican.

Yet this caricature of Jackson as an anti-white, anti-Semitic demagogue never reflected the man. The entire point of Jackson’s “Rainbow Coalition,” his vision of Americans from all backgrounds coming together for social justice, was overcoming such differences. Jackson’s political vision was always inclusive, always multiracial, and always opposed to bigotry and prejudice of all kinds, even if the man himself sometimes fell short.

For one thing, Jackson’s egalitarianism and support for a strong welfare state—including universal health care—did not contradict his emphasis on personal responsibility and the importance of the Church in Americans’ lives. As Frady notes, the South Carolina reverend was constantly hammering on these conservative-friendly themes, long before they became part of Ronald Reagan or Bill Clinton’s presidential campaigns.

“Black Americans must begin to accept a larger share of responsibility for their lives. For too many years we have been crying that racism and oppression have kept us down,” Jackson wrote inThe New York Times, in 1976. “That is true, and racism and oppression have to be fought on every front. But to fight any battle takes soldiers who are strong, healthy, spirited, committed, well‐trained and confident.”

The 1984 speech that so moved Baldwin remains one of the greatest articulations of American liberalism ever made. But I was too young to remember it, and it is his 1988 speech that I find indelible. In 1984, Jackson described America as a “quilt” with “many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread.” In 1988, he extended the metaphor—arguing that progress could not be made without the aid of people from very different backgrounds, with very different identities.

“Farmers, you seek fair prices and you are right—but you cannot stand alone. Your patch is not big enough. Workers, you fight for fair wages, you are right—but your patch of labor is not big enough. Women, you seek comparable worth and pay equity, you are right—but your patch is not big enough,” Jackson said. “Students, you seek scholarships, you are right—but your patch is not big enough. Blacks and Hispanics, when we fight for civil rights, we are right—but our patch is not big enough.”

Many obituaries have emphasized Jackson’s hunger for publicity. He was, indeed, no wallflower. But neither did he simply pose for the cameras. Jackson’s decades of activism demonstrated that he was sincere about his vision. When workers were striking, Jackson was there. When it was unpopular to support LGBTQ rights, Jackson did so anyway. When both conservatives and liberals were outraged over illegal immigration, Jackson insisted on mercy and understanding for the undocumented. Despite the “hymie” incident, Jackson never stopped condemning the evils of anti-Semitism, even as he supported Palestinian rights and statehood. Before Pat Buchanan or Donald Trump ran for president, Jackson was condemning “American multinationals” who “hire repressed labor abroad and fire free labor at home.”

The critics who caricatured him did not understand this sincerity—or perhaps they understood it far too well. His commitment to the people he once described as “the desperate, the damned, the disinherited, the disrespected, and the despised,” was real, and he dedicated his life to it.

[Clint Smith: Those who try to erase history will fail]

Jackson’s sincerity eventually overcame the stereotypes about him. In the early 1990s, only a third of white Americans viewed him favorably; by 1999, that number was close to 60 percent, including, The New York Times reported, many “self-described conservatives.”

Democratic leaders credited Jackson’s work registering Black voters with making otherwise-difficult gains in the wilderness of the Reagan era. He was a genuinely transformative figure, inspiring not just a generation of Black voters but Black officeholders, helping usher in an era of Black self-determination that eclipsed the previous peak during Reconstruction a century earlier. His exhortation to “keep hope alive” in an era of backlash was precisely what he did. Frady quotes former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown calling Jackson “the Jackie Robinson of American politics,” who would “spawn a whole lot of Little Leaguers in many cities and counties that you and I will never hear about.” That was, we now know, an understatement.

The epithet of “race hustler” or “race pimp” can be more accurately applied to many of Jackson’s critics, who perceived his multiracial populism as a threat. They tried to neutralize that threat by turning Jackson into a racial caricature that could be exploited to fan the fears of white Americans that they would be dispossessed, the same inversion of American history that continues to drive right-wing politics in the present. They did not make a caricature of Jackson because he was ridiculous; they tried to make him ridiculous because his vision was so powerful.

The post Do Not Be Cynical About Jesse Jackson appeared first on The Atlantic.