This obituary was originally published on March 6, 1966. It is being republished for a package for Women’s History Month. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them.

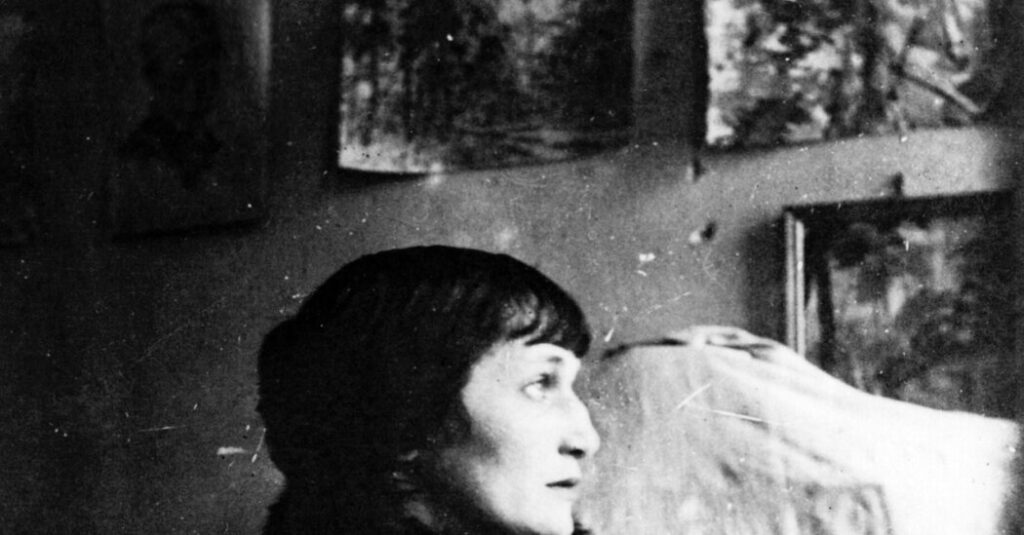

MOSCOW — Anna Akhmatova, the poet, died today, after a lifetime of controversy. According to Tass, the Soviet press agency, her age was 76.

Silenced in a Stalinist literary purge 20 years ago, Miss Akhmatova nevertheless remained a towering figure in Soviet literature and, with Boris Pasternak, was acknowledged the chief inspiration of the younger generation of liberal intellectuals.

Last summer, Miss Akhmatova traveled to Britain to receive an honorary doctorate in literature from Oxford University. She was awarded an Italian prize for the best poetry of 1965 for a collection of her works published in Rome.

In the Soviet Union, too, she received honors after her years of disgrace. The Writers Union quietly elected her to its presidium last year, and a major collection of her poetry was sold out within hours of its publication a few months ago.

Like Mr. Pasternak, who died in 1960, she had an influence that spread far beyond her writings, despite the Communist party’s attempts to demolish her stature.

She wrote of love and tenderness and solitude through times when Soviet writers were expected to write of heroism and triumph in Communism.

Inspiration to the Young

Andrei Voznesensky, a leading young poet, acknowledged her last year as “the matriarch of Russia’s poets.” Her poems, he said, are “a special element of culture” for the younger Soviet intellectuals.

Miss Akhmatova’s life spanned many Russias — the avant garde literary life of St. Petersburg (now Leningrad), the heyday of cultural experimentation in the early nineteen-twenties and the years of silence through Stalin’s purges.

In World War II, her deeply patriotic poems made her voice a symbol of resistance in besieged Leningrad.

From the period of the Leningrad siege is the poem “Courage.” The translation is by Avrahm Yarmolinsky, and appears in his “A Treasury of Russian Verse,” published by the Macmillan Company in 1949.

What hangs in the balance is no wise in doubt: We know the event and we brave what we know; Our clocks are all striking the hour of courage — That sound travels with us wherever we go. To die of a bullet is nothing to dread, To find you are roofless is easy to bear; And all is endured, O great language we love: It is you, Russian tongue, we must save, and we swear We will give you unstained to the sons of our sons; You shall live on our lips, and we promise you — never A prison shall know you, but you shall be free Forever.

Purge in 1946

On Aug. 14, 1946, the crackdown began, when Miss Akhmatova and the satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko were singled out by Stalin’s cultural chief, Andrei Zhdanov.

To Mr. Zhdanov, Miss Akhmatova represented “eroticism, mysticism and political indifference.” She stood for “art for art’s sake,” anathema to the ideals of socialist realism; her work was, he said, for no more than “the upper 10,000.”

“Her interests,” Mr. Zhdanov said, ending his denunciation, “were divided among the drawing room, the bedroom and the chapel.”

To Communists of the period, this was sinfulness of the highest degree. Miss Akhmatova was expelled from the Soviet Writers Union, as Mr. Pasternak was to be a decade later. She became a recluse, often, it was said, on the brink of starvation.

Rehabilitation started after Stalin’s death with limited new publication of Miss Akhmatova’s poems.

Even during her disgrace, she would receive letters from admirers she never knew, from workers and students who had heard of her works.

Husband Executed in 1921

Her first husband, the poet Nikolai Gumilev, had proclaimed himself a monarchist, even after the Bolsheviks seized power. He was executed by firing squad in 1921.

Anna Akhmatova — a literary pseudonym for Anna Andreyevna Gorenko — was married three times more, and there were frequent stories, some little more than rumors, of her love affairs.

An example of her work concerned with personal themes is this poem of 1940, also in Mr. Yarmolinsky’s volume:

Oh, how good the snapping and the crackle Of the frost that daily grows more keen! Laden with its dazzling icy roses, The white-flaming bush is forced to lean. On the snows in all their pomp and splendor There are ski tracks, and it seems that they Are a token of those distant ages When we two together passed this way.

Her books include “Evening,” (published in 1910); “The Rosary” (1912); “The White Flock” (1917); “Anno Domini” (1922); “A Selection from Six Books” (1940), and “Requiem,” not yet published in the Soviet Union.

The poet’s son, L.N. Gumilev, a scholar in Far Eastern studies who taught at the University of Leningrad, was imprisoned in the late nineteen-forties as part of the Stalinist persecution of Miss Akhmatova. He was freed late in 1956 or early 1957 and was restored to his teaching post.

The post Anna Akhmatova, Leading Soviet Poet, Is Dead appeared first on New York Times.