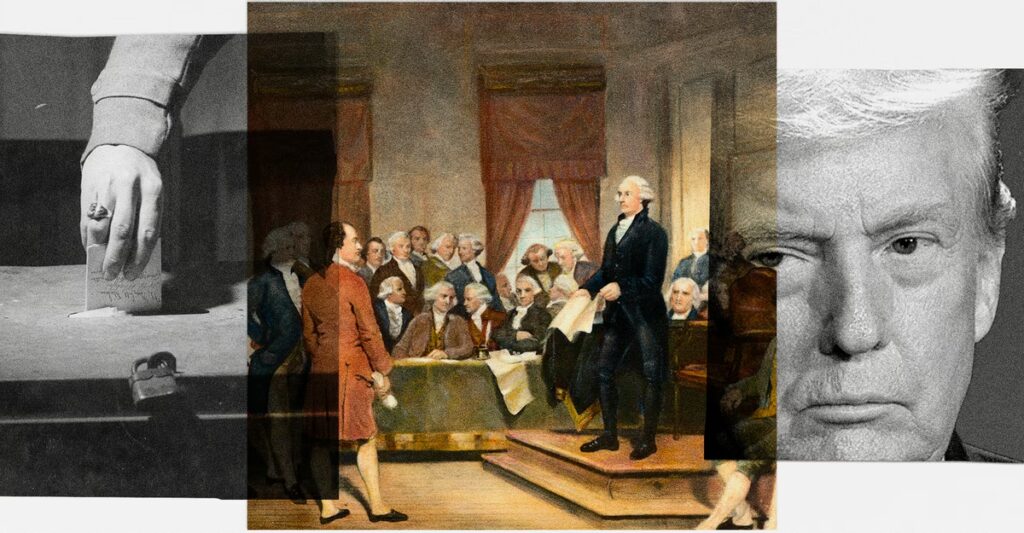

President Trump earlier this month repeated his call for the Republican Party to “nationalize” voting in the United States. “We should take over the voting, the voting in at least many—15 places,” he said. “The Republicans ought to nationalize the voting.” The next day, he added, “A state is an agent for the federal government in elections.”

The Framers would not have agreed. The Constitution does give Congress broad power to “make or alter” regulations about the time, place, and manner of elections. But at the same time, states were given primary control over elections and Congress was denied the power to determine voter qualifications. That’s because the Framers did not think election administration should be solely a federal endeavor. They sought to divide responsibility between the states and the federal government, to avoid the dangers of both federal military dictatorship and state hyper-partisanship. History has demonstrated the wisdom of their approach, and the Supreme Court has been skeptical of broad attempts to nationalize elections in the past.

In drafting the elections clause in 1787, the Founders at the Constitutional Convention attempted to balance their distrust of state legislatures as the source of partisan factions with their desire to maintain state control over voting qualifications. “The Legislatures of the States ought not to have the uncontrolled right of regulating the times places & manner of holding elections,” James Madison explained in a debate, according to notes taken at the time. He was concerned that partisan factions in a state might rig the electoral system to favor their own candidates. “Whenever the State Legislatures had a favorite measure to carry, they would take care so to mould their regulations as to favor the candidates they wished to succeed.”

[From the December 2025 issue: Trump’s plan to subvert the mid-terms is already under way]

Madison identified other “abuses” that might result, such as malapportionment. In 1787, South Carolina had a grossly malapportioned state legislature, which benefited slaveholders. The South Carolina delegates had proposed to deny the power of Congress to regulate the districts in their state, but their proposal failed. Other convention delegates, agreeing with Madison, said that congressional supervisory power over state elections was necessary to prevent voter fraud. Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania worried that “the States might make false returns and then make no provisions for new elections,” while Rufus King of Massachusetts feared that without a power to supervise elections, Congress might be unable to assess the validity of elections. The Founders also thought that a uniform time for national elections would ensure there was always a quorum in the House, which was necessary in times of emergency.

Once the Constitution was drafted and signed, it went to the state conventions for ratification. In the ratification debates, anti-Federalists—in particular Patrick Henry in Virginia—argued that the Convention’s allocation of broad authority over federal elections to Congress would enable congressional incumbents to entrench their own power, pulling tricks such as putting polling places in inconvenient locations. “When a numerous standing army shall render opposition vain, the Congress may complete the system of despotism,” the Anti-Federalist minority in Pennsylvania argued.

The Federalists countered that both the states and the federal government would share the power to determine election procedures. In “Federalist No. 60,” Alexander Hamilton emphasized the limits of the federal government’s sphere of authority over elections: Congress would have no power to determine the qualifications of voters or candidates, because the former was exclusively granted to state legislatures and the latter was fixed by the Constitution. Answering the Anti-Federalist charge that Congress might try to rig the elections to favor “the wealthy and the well-born” candidates, he said such a scheme would require a military coup and would be so objectionable that citizens would be inspired to “flock from the remotest extremes of their respective States to the places of election, to overthrow their tyrants.” Even Hamilton, the convention’s most robust defender of federal power, recognized a role for the states in the electoral process.

Congress did not exercise its power to nationalize election procedures until the Apportionment Act of 1842, which required all congressional elections to take place in contiguous, single-member districts rather than at-large elections. One goal was the protection of political minorities: Because a dominant faction, or even a bare majority, would win all of a state’s congressional seats in an at-large election, the framers of the statute thought single-member districts would facilitate higher levels of partisan fairness. However, as politics became more polarized, the law failed to deliver on its promise. Requiring single-member districts increased the opportunities for state legislatures to engage in partisan gerrymandering and prevented states from adopting alternative voting systems that were less vulnerable to partisan manipulation, such as proportional representation. The Supreme Court has stressed that Congress retains the power to ban partisan gerrymandering, but Congress has refused to use it.

[Read: A day of sorrow for American democracy]

At times, of course, federal control over elections and law enforcement has been crucial, most notably in service of enforcing civil rights. During both the Reconstruction era of the 1860s and ’70s and the civil-rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, it was only the threat of federal troops that led recalcitrant southern states to uphold the law—and once the troops were withdrawn, lawlessness prevailed.

In that first period, after the Civil War, the Reconstruction Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which outlawed racial discrimination in voting. This had long been a goal of abolitionists, most significantly Frederick Douglass. Opponents of the Fifteenth Amendment insisted that state power, not federal power, should be the source of voting regulations, citing Hamilton’s ideas in The Federalist Papers. Supporters of the amendment invoked Hamilton as well: George Sewall Boutwell of Massachusetts quoted Hamilton’s statement in “Federalist No. 59” that “nothing can be more evident than that an exclusive power of regulating elections for the national Government, in the hands of the State Legislatures, would leave the existence of the Union entirely at their mercy.”

After the Civil War, as the reign of Ku Klux Klan violence grew to terrorize Black Americans, it became clear that the voting rights guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment could be enforced only under federal authority. Beginning in 1870, Congressional Republicans responded by passing three Enforcement Acts, which, among other things, forbade people from banding together to harass Black voters and empowered judges and United States marshals to supervise polling places. Unfortunately, after the disputed election of 1876, political support for Black voting rights collapsed, and Republicans withdrew military troops from the South. The Supreme Court then made things worse by repeatedly striking down key provisions of the Enforcement Acts, as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1875, as violations of states’ rights. The combination of diminished political will and judicial restrictions on federal power once again placed the responsibility for organizing federal elections primarily in the hands of the states, to terrible effect.

President Trump’s proposal to nationalize elections isn’t an attempt to enforce civil rights but to achieve partisan advantage. The Framers were no stranger to partisan manipulation of the electoral system. In one of his lowest moments, Hamilton proposed changing election procedures in New York State after the election had occurred in order to prevent Thomas Jefferson from winning the presidency. Nevertheless, they believed that congressional power over elections was necessary to standardize the time, place, and manner of elections across the entire United States, not to allow a partisan national majority to punish states and jurisdictions where the opposite party prevailed.

If Congress passed President Trump’s proposal to federalize elections in 15 places—presumably Democratic jurisdictions—is there any chance the Supreme Court would uphold it? It’s possible. The Court in recent years has sanctioned broad congressional power under the elections clause, upholding statutes that regulate redistricting, voter registration, campaign finance, corruption, primaries, and recounts. That said, in striking down portions of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County, the Court expressed its disapproval of federal voting legislation that treats different states differently.

[Listen: If the voting rights act falls]

The closest historical analogue to Trump’s proposal to nationalize elections is the federal elections bill proposed in 1890 by Henry Cabot Lodge. Known as the “Force Bill,” the act would have authorized federal courts, backed by military force, to supervise state elections by appointing officials who could oversee registration, certify the election results, prevent noncitizens from voting, and reject fraudulent results. In his biography of Daniel Webster, Lodge had concluded that, throughout American history, “if illegal and partisan State resistance had always been put down with a firm hand, civil war might have been avoided.” Unlike Trump’s proposal, however, the Lodge Bill did not single out Democratic cities for federal supervision but instead applied neutrally, because its goal was to secure Black voting rights rather than Republican partisan advantage.

In the end, these election disputes have confirmed the wisdom of the Founders’ decision to divide the power to regulate elections between the states and Congress. State involvement helps combat congressional self-dealing and undemocratic incumbent retrenchment, while congressional oversight helps curb state abuses, such as malapportionment and partisan vote suppression. And perhaps most important, by empowering Congress, not the president, to remedy deficient state electoral schemes, the Constitution prevents presidents from rewriting the election code by executive fiat and thus provides an additional safeguard against military dictatorship. Americans today should abide by its guidance.

The post The Founders Would Have Opposed ‘Nationalizing’ Elections appeared first on The Atlantic.