Tamar Abrams had a lousy couple of years in 2022 and ’23. Both her parents died; a relationship ended; she retired from communications consulting. She moved from Arlington, Va., to Warren, R.I., where she knew all of two people.

“I was kind of a mess,” recalled Ms. Abrams, 69. Trying to cope, “I was eating myself into oblivion.” As her weight hit 270 pounds and her blood pressure, cholesterol and blood glucose levels climbed, “I knew I was in trouble health-wise.”

What came to mind? “Oh, oh, oh, Ozempic!” — the tuneful ditty from television commercials that promoted the GLP-1 medication for diabetes. The ads also pointed out that patients who took it lost weight.

Ms. Abrams remembered the commercials as “joyful” and sometimes found herself humming the jingle. They depicted Ozempic-takers cooking omelets, repairing bikes, playing pickleball — “doing everyday activities, but with verve,” she said. “These people were enjoying the hell out of life.”

So, just as such ads often urge, even though she had never been diagnosed with diabetes, she asked her doctor if Ozempic was right for her.

Small wonder Ms. Abrams recalled those ads. Novo Nordisk, which manufactures Ozempic, spent an estimated $180 million in direct-to-consumer advertising in 2022 and $189 million in 2023, according to MediaRadar, which monitors advertising.

By last year, the sum — including radio and TV commercials, billboards, and print and digital ads — had reached an estimated $201 million, and total spending on direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs topped $9 billion, by MediaRadar’s calculations.

Novo Nordisk declined to address those numbers.

Should it be legal to market drugs directly to potential patients? This controversy, which has simmered for decades, has begun receiving renewed attention from both the Trump administration and legislators.

The question has particular relevance for older adults, who contend with more medical problems than younger people and are more apt to take prescription drugs. “Part of aging is developing health conditions and becoming a target of drug advertising,” said Dr. Steven Woloshin, who studies health communication and decision making at the Dartmouth Institute.

The debate over direct-to-consumer ads dates to 1997, when the Food and Drug Administration loosened restrictions and allowed prescription drug ads on television as long as they included a rapid-fire summary of major risks and provided a source for further information.

“That really opened the door,” said Abby Alpert, a health economist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

The introduction of Medicare Part D, in 2006, brought “a huge expansion in prescription drug coverage and, as a result, a big increase in pharmaceutical advertising,” Dr. Alpert added. A study she co-wrote in 2023 found that the number of pharmaceutical ads were much more prevalent in areas with a high proportion of residents over 65.

Industry and academic research have shown that ads influence prescription rates. Patients are more apt to make appointments and request drugs, either by brand name or by category, and doctors often comply. Multiple follow-up visits may ensue.

But does that benefit consumers? Most developed countries take a hard pass. Only New Zealand and, despite the decade-long opposition of the American Medical Association, the United States allow direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising.

Public health advocates argue that such ads encourage the use and overuse of expensive new medications, even when existing, cheaper drugs work as effectively. (Drug companies don’t bother advertising once patents expire and generic drugs become available.)

In a 2023 study in JAMA Network Open, for instance, researchers analyzed the “therapeutic value” of the drugs most advertised on television, based on the assessments of independent European and Canadian organizations that negotiate prices for approved drugs.

Nearly three-quarters of the top advertised medications didn’t perform markedly better than older ones, the analysis found.

Trump Administration: Live Updates

Updated

- In Hungary, Rubio stresses Trump’s support for Viktor Orban.

- Indonesia says it’s preparing thousands of peacekeeping troops for Trump’s Gaza plan.

- The Department of Homeland Security funding fight centers on immigration agents.

“Often, really good drugs sell themselves,” said Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, senior author of the study and director of the Program on Regulation, Therapeutics and Law at Harvard University.

“Drugs without added therapeutic value need to be pushed, and that’s what direct-to-consumer advertising does,” he said.

Opponents of a ban on such advertising say it benefits consumers. “It provides information and education to patients, makes them aware of available treatments and leads them to seek care,” Dr. Alpert said. That is “especially important for underdiagnosed conditions,” like depression.

Moreover, she wrote in a recent JAMA Health Forum commentary, direct-to-consumer ads lead to increased use not only of brand name drugs but also of non-advertised substitutes, including generics.

The Trump administration entered this debate last fall, with a presidential memorandum calling for a return to the pre-1997 policy severely restricting direct-to-consumer drug advertising.

That position has repeatedly been urged by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has charged that “pharmaceutical ads hooked this country on prescription drugs.”

At the same time, the F.D.A. said it was issuing 100 cease-and-desist orders about deceptive drug ads and sending “thousands” of warnings to pharmaceutical companies to remove misleading ads. Dr. Marty Makary, the F.D.A. commissioner, blasted drug ads in an essay in The New York Times.

“There’s a lot of chatter,” Dr. Woloshin said of those actions. “I don’t know that we’ll see anything concrete.”

This month, however, the F.D.A. notified Novo Nordisk that the agency had found its TV spot for a new oral version of Wegovy false and misleading. Novo Nordisk said in an email that it was “in the process of responding to the F.D.A.” to address the concerns.

Meanwhile, Democratic and independent senators who rarely align with the Trump administration also have introduced legislation to ban or limit direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical ads.

Last February, Senator Angus King, independent of Maine, and two other sponsors introduced a bill prohibiting direct-to-consumer ads for the first three years after a drug gains F.D.A. approval.

Mr. King said in an email that the act would better inform consumers “by making sure newly approved drugs aren’t allowed to immediately flood the market with ads before we fully understand their impact on the general public.”

Then, in June, he and Senator Bernie Sanders, independent of Vermont, proposed legislation to ban such ads entirely. That might prove difficult, Dr. Woloshin said, given the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling protecting corporate speech.

Moreover, direct-to-consumer ads represent only part of the industry’s promotional efforts. Pharmaceutical firms actually spend more money advertising to doctors than to consumers.

Although television still accounts for most consumer spending, because it’s expensive, Dr. Kesselheim pointed to “the mostly unregulated expansion of direct-to-consumer ads onto the web” as a particular concern. Drug sales themselves are bypassing doctors’ practices by moving online.

Dr. Woloshin said that “disease awareness campaigns” — for everything from shingles to restless legs — don’t mention any particular drug but are “often marketing dressed up as education.”

He advocates more effective educational campaigns, he said, “to help consumers become more savvy and skeptical and able to recognize reliable versus unreliable information.”

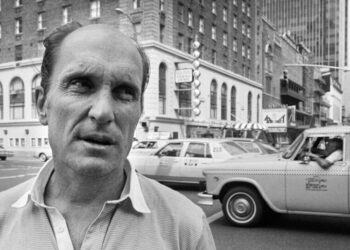

Dr. Woloshin and his late wife Dr. Lisa Schwartz, for example, designed and tested a simple “drug facts box,” similar to the nutritional labeling on packaged foods, that summarizes and quantifies medications’ benefits and harms.

For now, consumers have to try to educate themselves about the drugs they see ballyhooed on TV.

Ms. Abrams read a lot about Ozempic. Her doctor agreed that trying it made sense. (There are no generic GLP-1 drugs yet, although compounding pharmacies sell nonbranded versions.)

Her doctor referred Ms. Abrams to an endocrinologist, who decided that her blood glucose was high enough to warrant treatment. Three years later and 90 pounds lighter, she feels able to scramble after her 2-year-old grandson, enjoys Zumba classes and no longer needs blood pressure or cholesterol drugs.

So Ms. Abrams is unsure, she said, how to feel about a possible ban on direct-to-consumer drug ads.

“If I hadn’t asked my new doctor about it, would she have suggested Ozempic?” Ms. Abrams wondered. “Or would I still weigh 270 pounds?”

The New Old Age is produced through a partnership with KFF Health News.

The post Should Drug Companies Be Advertising to Consumers? appeared first on New York Times.