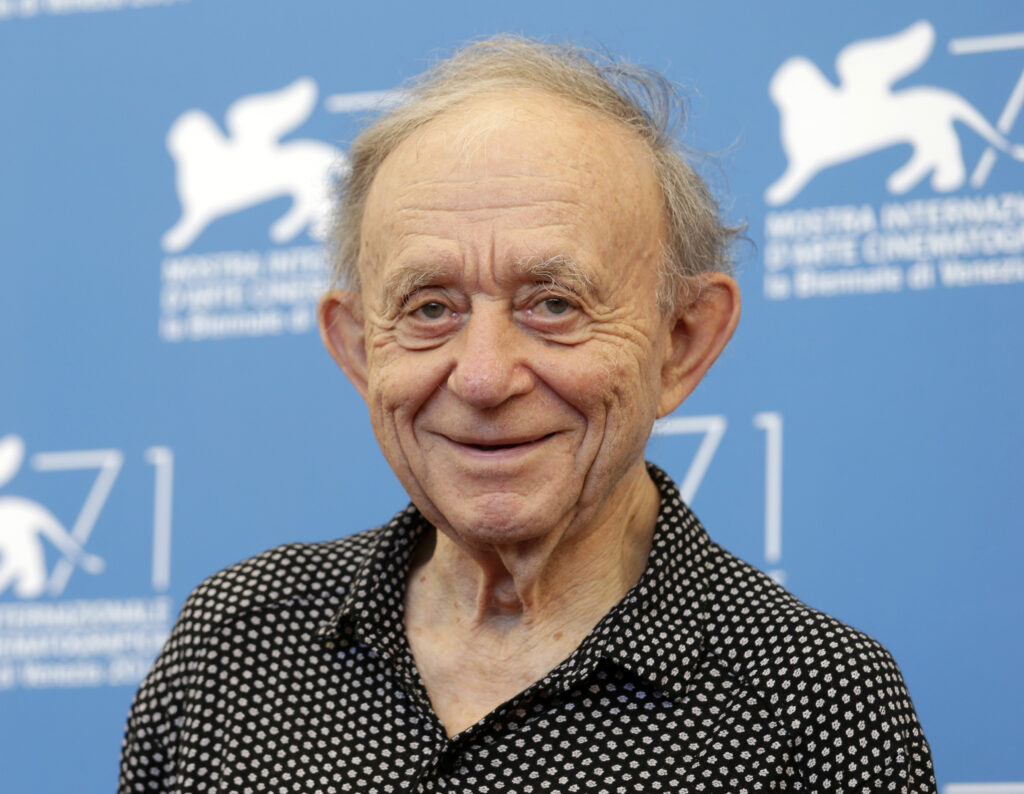

Frederick Wiseman, a dean of documentary filmmaking whose immersive chronicles of communities and institutions — including a psychiatric hospital, high school, dance troupe, monastery, Chicago public housing project and polyglot enclave in Queens — formed a vast mosaic of contemporary American life, died Feb. 16 at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was 96.

His death was announced by his family and his film company, which did not provide a specific cause.

With a wrinkled brow, wide-set ears and a windblown shock of hair, Mr. Wiseman continued making documentaries into his 90s, carrying a boom microphone alongside his camera operator while filming for 12 or 14 hours each day. His goal, he once told the New York Times, was “to do a natural history of the way we live.”

To that end, he embedded in a single location for weeks at a time, crafting 45 meditative, simply titled films such as “High School” (1968), a portrait of a draconian public school in Philadelphia; “Missile” (1988), about a 14-week training course for Air Force officials who man nuclear-weapon silos; and “City Hall” (2020), an exploration of Boston’s nine-story municipal center and the residents who come there to contest parking fines, get married or petition the mayor.

In an era of shrinking attention spans, Mr. Wiseman’s movies were defiantly long and slow-moving, frequently lasting three hours and — in the case of “Near Death” (1989), shot at an intensive care unit in Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital — sometimes stretching to six. They featured no voice-over narration, talking-head interviews or musical score and centered more on places than on individual people, who were identified only if their name was used in conversation.

“Walt Whitman wrote that ‘the United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem,’ and in a Whitmanian temper I would argue that Frederick Wiseman is the greatest American poet,” New York Times film critic A.O. Scott wrote in 2018, reviewing Mr. Wiseman’s film “Monrovia, Indiana,” about a farming community in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election.

Through his movies, Scott added, “You arrive at meaning through patterns and rhythms, and you have to do some work to apprehend the structure and the themes. In return, you arrive at a kind of knowledge that’s impossible to summarize, and also to forget.”

A Yale Law School graduate who turned from teaching to filmmaking, Mr. Wiseman was known as a muckraker early in his career. His first film, “Titicut Follies” (1967), exposed the wretched conditions of a mental institution for prisoners in Massachusetts, and subsequent works tackled topics such as criminal justice, poverty and domestic violence.

But Mr. Wiseman battled those who sought to label him anything other than a filmmaker. He abhorred didacticism, declaring that his movies had no overriding message or lesson, and insisted that documentaries could be just as “complex and subtle as a good novel.”

Nonetheless, he was often placed within the documentary school known as cinema verité (Mr. Wiseman dismissed the term as “a vomit-special”), in which a subject is shown without commentary or adornment, and the camera operator seems to be a fly on the wall. In one Wiseman film, a child tells a counselor that when her abusive father dies, “I won’t cry”; in another, a nurse tells an 83-year-old patient, “Your lungs aren’t going to get better, and so the act of putting you on the machine is almost a futile effort.”

While his movies featured real people in real situations, Mr. Wiseman contended that editing effectively turned his films into works of fiction. His decision to snip here or trim there, turning hundreds of hours of raw footage into a cohesive documentary, was in his view scarcely different from a writer’s shaping a novel or play.

Perhaps his most famous sequence — one that he later came to regret, deeming it heavy-handed — came in “Titicut Follies,” when he intercut the brutal forced-feeding of an inmate with shots of the man’s corpse being tenderly prepared for burial.

Filmed for much of 1966 at the State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, “Titicut Follies” was named for the annual variety show put on by the hospital’s staff and inmates. Mr. Wiseman was teaching law at Boston University when he began taking students to the institution, trying to show future judges and prosecutors the sort of place they might sentence future criminals.

“It seemed to me that nobody had really begun to do this, and that there are all kinds of great stories that Hollywood and the telly never did,” he later told the Times. “I was fed up with all their fantasies. I was particularly interested in using the new advances in film technology — lightweight, handheld cameras and portable tape recorders — which made it possible for even a two-man team to go out and tell the stories of ordinary people.”

While “Titicut Follies” was hailed by critics such as Roger Ebert, who called it “one of the most despairing documentaries I have ever seen,” it faced stiff opposition from Massachusetts legislators, who argued that its graphic depiction of inmates — kept naked in barren rooms, bullied by their guards — violated convicts’ privacy and dignity.

In 1968, a Massachusetts Superior Court judge banned the movie, calling it “a nightmare of ghoulish obscenities.” Educators and mental health professionals were granted exceptions and allowed to see the film, and after several Bridgewater inmates died by suicide, Mr. Wiseman saw an opening and appealed the ban. A Massachusetts Superior Court judge sided with him in 1991, ruling that privacy issues were outweighed by First Amendment concerns.

Ironically, Mr. Wiseman later said, his movie was screened annually to Bridgewater employees, “as a training film in what not to do.”

Not a ‘neat little package’

Frederick Wiseman was born in Boston on Jan. 1, 1930. His mother, born to Jewish immigrants from Poland, was an administrator in the psychiatric department of Children’s Hospital; his father, born into a Jewish family in Russia, was a lawyer.

As a boy, Frederick pored over baseball records, memorizing statistics that dated to the 1890s, and began making a regular pilgrimage to the neighborhood movie theater, where his favorite films included the comedies of the Marx Brothers and Laurel and Hardy.

He attended Rivers Country Day School (now the Rivers School) in the Boston suburb of Weston, and received a bachelor’s degree in 1951 from Williams College. Lacking direction, knowing only that he wanted to avoid being drafted for the Korean War, he decided to follow his father into the family business and, in 1954, graduated from Yale Law School.

Mr. Wiseman nonetheless served briefly in the Army — he was stationed stateside as a court reporter — and in 1955 married Zipporah Batshaw, a fellow Yale Law graduate. After he was discharged from the military the following year, they moved to Paris, where he studied at the Sorbonne, practiced law and picked up an 8mm movie camera, amusing himself by making short films of Parisian street life.

Filmmaking stuck. Returning home to Massachusetts, he supported himself by teaching law and acquired the rights to Warren Miller’s novel “The Cool World,” about Harlem gangs, which he then produced as a movie in 1963.

Mr. Wiseman later adapted his 1975 documentary “Welfare” into an opera and, somewhat remarkably, turned “Titicut Follies” into a ballet. But for the most part he focused on documentary filmmaking, supported by funding from institutions such as the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ford Foundation. His films were televised on PBS and released through a distribution company named for his wife, Zipporah Films.

Mr. Wiseman received prizes including an honorary Oscarin 2016, the George Polk Career Award, a MacArthur fellowship, a Peabody Award and two best-documentary Emmy Awards, for “Law and Order” (1969) and “Hospital” (1970). The latter also earned him an Emmy for best documentary director.

His wife died in 2021. Survivors include two sons, David and Eric; and three grandchildren.

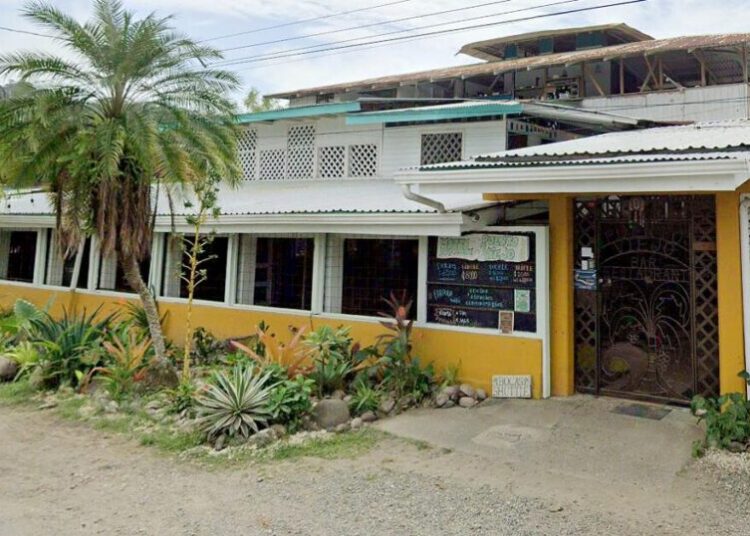

Mr. Wiseman sometimes found his subjects outside the United States, documenting the Sinai Peninsula in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War and spending time at the Paris Opera Ballet. His most recent film, “Menus-Plaisirs — Les Troisgros” (2023), explored the operation of a family-run, Michelin-starred restaurant in central France.

More often, he stayed closer to home, making nine films in Greater New York alone — 10 including “The Garden,” a 2005 documentary on Madison Square Garden that was blocked from release amid a legal battle with the arena’s owners.

Despite the acclaim from critics and his peers, he often faced questions about the length of his movies, and whether it was really necessary to include extended, unbroken sequences of boardroom meetings or subdued therapy sessions.

“Life doesn’t come in this neat little package where there is an ultimate triumph or failure,” he told the New York Times in 1988, upon the release of a four-film series on the Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind. “Most of life just keeps going on and that’s what I’m trying to show. If you can sum it up in 25 words or less, you should read those 25 words, not make a movie about it.”

“It’s condescending to make conclusions for people,” he added. “Maybe they end up like I did after I made ‘Deaf’ and ‘Blind.’ I began to think about how I learned to tie my shoes or cross a street. I saw what an enormous effort it took that man in the fourth film [‘Adjustment & Work’] to learn how to fold a washcloth — a whole morning’s work.

“I think about him every time I fold anything now.”

The post Frederick Wiseman, a master of immersive documentaries, dies at 96 appeared first on Washington Post.