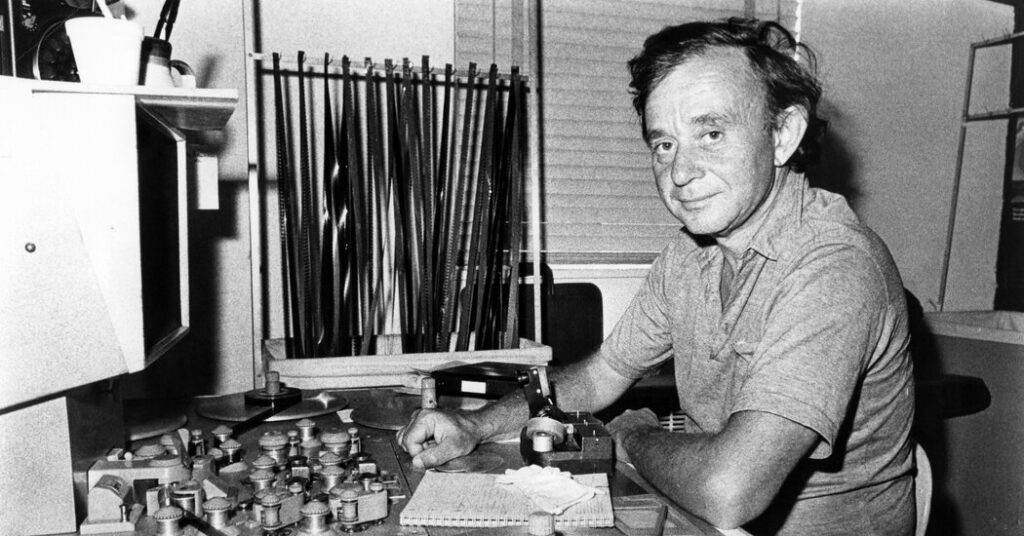

Frederick Wiseman, a director whose rigorously objective explorations of social and cultural institutions constitute one of the more revered bodies of work in American documentary filmmaking, died on Monday. He was 96.

His family announced his death through Zipporah Films, the distribution company he founded in 1971 in Harpswell, Maine. It did not say where he died but noted that he “considered Cambridge, Mass.; Northport, Maine; and Paris, France” to be his homes.

Mr. Wiseman, who received an honorary Academy Award in 2016, was among the most influential directors of nonfiction cinema.

He consistently dismissed categorizations of his work. “I like to call them films” rather than documentaries, he said, because he found the word “documentary” limiting. But he was as closely associated as anyone with the vérité documentary.

And though he denied that his movies had any political agenda, he was no stranger to controversy. His directorial debut, “Titicut Follies” (1967), a harrowing portrait of the Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane in Massachusetts, remains the only film ever banned in the United States for reasons other than obscenity, immorality or national security. (The ban, imposed by Massachusetts on the grounds that the film violated the inmates’ privacy, was lifted in 1991; the film subsequently aired on PBS.)

Mr. Wiseman’s last films were among his best received. The novelist Jay Neugeboren, writing in The New York Review of Books, called “In Jackson Heights” (2015), a panoramic portrait of one of the country’s most diverse neighborhoods, in Queens, the “most richly textured and sumptuously beautiful” of Wiseman’s documentaries. Reviewing “Ex Libris: The New York Public Library” (2017) for The New York Times, Manohla Dargis called it “one of the greatest movies of Mr. Wiseman’s extraordinary career and one of his most thrilling.”

Since then, Mr. Wiseman had released “Monrovia, Indiana” (2018), a study of small-town Middle America; the long-in-the-works “City Hall” (2020), a four-and-a-half-hour examination of urban bureaucracy set in Boston, his hometown; and “Menus-Plaisirs — Les Troisgros” (2023), a loving four-hour dissection of a three-Michelin-star French restaurant and the family that runs it.

“Titicut Follies” became the stylistic template for Mr. Wiseman’s subsequent films, which were free of narration and shot with available light, and which often concerned public institutions and the abuses therein. Among his better-known works are “High School” (1968), “Welfare” (1975), “Public Housing” (1997) and “Domestic Violence” (2002).

Uncovering governmental or administrative malfeasance, however, was never his aim.

“There’s a common assumption that my movies are exposés,” Mr. Wiseman said in a 2011 interview for this obituary, “and I don’t think they are. You can certainly argue that a movie like ‘Titicut Follies’ is in part an exposé, but you couldn’t make a movie about Bridgewater without showing how horrible it was.”

He added: “There are people who think if I don’t make a movie about how poor people are being taken advantage of by the system, it’s not a real Fred Wiseman movie. And I think that shows a complete misunderstanding about what I’m doing.”

Mr. Wiseman was born on New Year’s Day 1930 in Boston. His father, Jacob, was a lawyer whose work involved helping Jewish émigrés escape an increasingly antisemitic Europe. His mother, Gertrude, had aspired to be an actress, only to have her dream thwarted by her father. Mr. Wiseman’s interest in theater was kindled by his mother’s uncanny talent as a mimic.

By his own admission a bad student who “daydreamed my way through high school,” Mr. Wiseman attended Williams College and then Yale Law School, “because I didn’t know what else to do,” he recalled in an autobiographical essay written for the book “Frederick Wiseman,” which accompanied a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010.

The other reason for his attending Yale was the Korean War draft. “Even law school seemed to be, to my keen analytical mind, a better alternative than going to war,” Mr. Wiseman wrote.

Law school resulted, however obliquely, in Mr. Wiseman’s career as a documentarian. Upon leaving Yale in 1954 he was drafted anyway. He became a clerk typist, was trained as a court reporter at the University of Virginia and was assigned to the judge advocate general’s office at Fort Benning, Ga. Looking to take advantage of an Army regulation that allowed early discharge to soldiers who planned to attend school, he applied and was admitted to the Sorbonne, and studied law in Paris on the G.I. Bill.

This was followed by a position at Boston University School of Law, where Mr. Wiseman taught subjects he later claimed to know little about: legal writing, legal medicine, family law and copyright. To compensate for his lack of expertise, he recalled, he would take students on field trips to places “where defendants would end up if they were poorly represented or overzealously prosecuted.” One of those places was the Bridgewater hospital.

Mr. Wiseman’s one brush with filmmaking before “Titicut Follies” was as the producer of “The Cool World” (1963), a drama directed by Shirley Clarke and adapted from a Warren Miller novel of the same name that Mr. Wiseman liked so much that he acquired the rights. The experience of producing that movie, he later said, persuaded him to direct and edit his own films.

His relationship with the superintendent at Bridgewater, which he had visited frequently with students, opened the doors to the making of “Titicut Follies.” (“Titicut” is a Native American word that refers to the nearby Taunton River.) This set him on the path to making several dozen other documentaries, most of which take an unblinking, aesthetically spare look at unlit corners of American life.

Although his subject matter was almost always American, he occasionally ventured abroad to tackle subjects that were, in his words, “not possible in America,” in films like “La Comédie-Française ou L’Amour Joué” (1996), “La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet” (2009) and “Crazy Horse” (2011), about the erotic nightclub of the same name in Paris.

“I don’t know if I can offer a general definition of what I’m doing,” Mr. Wiseman said in 2011, “except to say I’m trying to create dramatic structures out of ordinary experience, under a variety of differing circumstances, so the cumulative effect will be a series of thematically interrelated films that record how people thought and lived and worked over the course of time that I made the movies. And how that behavior is in part reflected in institutions. And how institutions are to a certain extent microcosms for a larger society.

“I try to avoid definitions or theories,” he continued. “That’s a sort of general statement, which I don’t particularly like having made. But I just made it.”

Mr. Wiseman’s approach to his films — shot in what he wryly referred to as “wobblyscope,” thanks to his hand-held camera — was perhaps never better expressed than during a face-off with his fellow documentarian Werner Herzog, onstage at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival.

Mr. Herzog, who had been espousing a theory of “ecstatic truth” and a willingness to manipulate his nonfiction films to achieve something sublime, confided to the audience that a shot apparently made through a dewdrop in his film “The White Diamond” had actually been made through a leaf to which glycerin had been applied. Asked whether he had ever done anything similar, or would, Mr. Wiseman said he had not, but admitted that he might change a lightbulb if a room seemed too dark.

Changing his films was another story. Likening him to Howard Roark, the hero of Ayn Rand’s novel “The Fountainhead,” the filmmaker Errol Morris, a fan of Mr. Wiseman’s work, said Mr. Wiseman “would rather blow up the building he designed than remove a doorknob.” The result, over the years, has included films of virtually unparalleled length — his 1989 film “Near Death,” set in a Boston hospital, is nearly six hours long — and a consequent lack of commercial viability.

“You’d think it would be easy for me to raise money because I’ve made a lot of movies,” Mr. Wiseman said. “But it’s not.”

The only time filmmaking was not a financial struggle for him was from 1971 to 1981, when he had two five-year contracts with WNET, the New York public television station, arranged by Fred W. Friendly, then with the Ford Foundation.

“That was nirvana,” Mr. Wiseman recalled, “because I knew I could just go from film to film without stopping to raise money. WNET certainly had to approve the subject matter. But they never disapproved of the subject matter.”

He added, “The cliché about political pressure, as far as I’m concerned, is a nonissue.” With the exception of “Titicut Follies,” the only Wiseman film that became a subject of contention was “The Garden,” his 2004 movie about Madison Square Garden, which remains unreleased.

“They brought suit,” he said of the Garden’s owners, “and I countersued. But the reason the film hasn’t been shown hasn’t to do with the Garden; we worked out our differences. The reason the film hasn’t been seen is over whether I could get permission to use some of the music, complicated by the fact that originally it was my assumption that the Garden had made all of those arrangements. Someday it will be.”

Mr. Wiseman is survived by his two sons, David and Eric, and three grandchildren. He met his wife, Zipporah Batshaw Wiseman, at Yale in 1954, and they married in 1955. She died in 2021 after a distinguished legal career.

In addition to his honorary Academy Award, Mr. Wiseman received honors including a career achievement award from the Los Angeles Film Society in 2013 and the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement from the Venice Film Festival in 2014. He never won a competitive Oscar, but he won Emmy Awards for the documentaries “Law and Order” (1969) and “Hospital” (1970).

Although Mr. Wiseman was a role model for generations of idealistic documentarians, his own view of the genre was the opposite of misty-eyed.

“I don’t know what causes social change,” he said in 2011. “But I don’t think it is documentary filmmaking. It’s one thing to start out with a naïve belief or the pious wish that that would be the case, but it certainly is not the case, and it’s ultimately a naïve and presumptuous view.”

Mr. Wiseman edited virtually all his own films. “A fiction film has a script,” he said, “so at the very least the chronology is determined in advance. But a documentary film of the kind I make, it’s reversed: I write the script in the editing.”

He continued: “I’m not saying there aren’t choices in the editing in a fiction film, because of course there are. But the range of choices aren’t anywhere near as great as they are in a documentary.”

In “La Danse,” for example, he turned about 150 hours of raw footage into a film of 2 hours 45 minutes, so “the ratio of film shot to film used was about 50 to 1.”

Shooting so much, Mr. Wiseman said, was just a logical result of the nature of his artistic pursuit. “I am trying to harvest a crop,” he said, “which I have not planted, and which may not exist.”

The post Frederick Wiseman, 96, Penetrating Documentarian of Institutions, Dies appeared first on New York Times.