It’s just after 2 p.m. on a Tuesday, and the televisions in the New Heights Grill are showing the only programming that matters to the bar’s patrons: a women’s hockey game unfolding thousands of miles away.

On the screens, Laila Edwards is patrolling the ice for the United States hockey team in its game against Canada, with the same steady focus as she did for the Cleveland Barons boys squirts team and the Cleveland Heights Tigers mites team.

Edwards grew up a slapshot away from the restaurant, where two men sitting near the door at the table they call Table One recall how they used to play hockey with her father. At the bar, a woman wearing a black and yellow Cleveland Heights High School hockey sweatshirt mentions that her son played with Edwards’s older brother. A few tables away, closer to the kitchen, sits a couple who after receiving a text from their daughter opted to change their lunch plans and, suspecting the game would be on at New Heights, eat there instead.

In Cleveland Heights, you show up for your own, and Edwards, 22, is not just hockey royalty but an avatar of the city’s inclusive ethos. She is the first Black woman to play for the U.S. hockey team and for the American team at the Olympics. The city is as proud of her and its other two famous athletes — the Super Bowl champions Jason and Travis Kelce, both of whom are Heights High graduates — as it is of its transformation from a rural farming community into an integrated inner-ring suburb.

The city’s slogan, “All Are Welcome,” guides civic life. Pride flags ripple above front doors and Black Lives Matter placards pop up in front lawns. Restaurants serving Ethiopian, Italian, Turkish and Trinidadian fare line Lee Road, the commercial street not far from Edwards’s home.

But Cleveland Heights, a city of about 45,000 just east of Cleveland, wasn’t always a melting pot. Black residents who moved here in the 1960s encountered violence and intimidation, with real estate agents denying them house viewings and their homes being bombed. “We have not always been a place where everybody was welcome,” said Marian J. Morton, a retired history professor who has written books on Cleveland Heights.

Residents, including Edwards’s paternal grandmother, mobilized to support integration. Today, Black residents make up about 40 percent of the population and white residents account for 46 percent, according to the latest census data. The city’s motto of inclusion “speaks to the fact we are very self-consciously and proudly racially and economically diverse and inclusive,” Morton said.

Edwards was 3 when she first strapped on ice skates, accompanying her older siblings, Chayla and Bobby, to the public skate program nearly every day at the Cleveland Heights Community Center. That was where her father, Robert Edwards, first started playing when he was 10, eventually playing at Heights High his senior year.

At 5, Edwards joined the Cleveland Heights Tigers Mites B team, and even then, playing with mostly older boys, she showed preternatural skill. Edwards, the only Black child on her team, had good balance with the stickhandling skills and hockey intelligence to match, said Pat Bauman, coach of Edwards’s first Mites team, which won the city playoff championship.

“That’s how she started her career out — being a champion of the lowest level of hockey for the youngest children in the city,” Bauman said.

Edwards soon outgrew suburban hockey. She and Chayla played for boys’ AAA teams around Cleveland and for an elite girls team based in Pittsburgh. At 13, she moved four hours away, to Rochester, N.Y., to attend Bishop Kearney High School, a private school with a top-tier girls’ hockey program.

She followed Chayla to the University of Wisconsin, where they were on the team that won a 2023 N.C.A.A. championship. Last season, as a junior helping the Badgers capture another national title, Edwards led the N.C.A.A. with 35 goals and was a top three finalist for the Patty Kazmaier Award, given annually to the top women’s college hockey player.

At every turn, Cleveland Heights has followed her journey with delight.

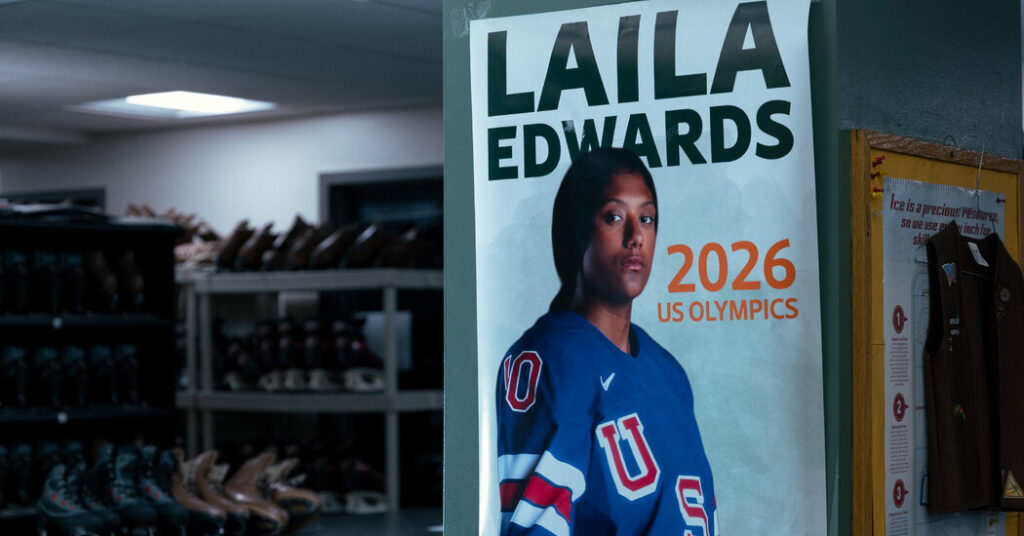

Pictures of Edwards in her U.S. team jersey decorate walls and bulletin boards of the community center, which held a watch party for the Olympic game against Finland. Gold No. 10 balloons — Edwards’s Olympics number — float behind the rental skate counter. Her Mites B championship banner hangs on the wall at the community center’s North Rink, just near the one adorned with her sister’s and father’s names.

“I think it’s so cool she’s been in this ice rink and played here,” Corrie Fleck, 10, who plays on the Eastside Tigers 10-and-under team, said after a recent practice. Around her, girls wearing jerseys signed by Edwards waddled by on skates. “This ice rink feels so ordinary, but then a superstar is from here.”

Last week, a group of children raced over to Robert Edwards at the community center and asked if he was Laila’s father. Moments later, Edwards was on FaceTime from Italy as a bunch of boys wrestled for the phone to show her all the posters of her hanging on the walls.

At least one restaurant has opened early and closed late for fans to catch her Olympic games. Community members, including the Kelces and families from Shaker Heights where Edwards’s older brother Bobby coaches a squirts team, have helped raise money for her family’s expenses to Italy.

The enthusiasm has also reached Roxboro Elementary School, where Laila and her siblings went to school, and where her nephew, Shiloh Stewart, also a hockey player, proudly wears his U.S.A. hockey hat in class. Shiloh’s kindergarten classroom is decorated with Olympic rings and newspaper articles of Edwards. Drawings of her fill the hallway, with loopy, pencil-scrawled messages of “Go U.S.A.” and “You are the best.” The class sent some to Edwards in Italy. Standing on a balcony and wearing a Heights T-shirt, Edwards thanked the students.

“Dream big, little ones,” she said in a recorded video.

Since learning about Edwards in school, Kennedy Davis, 6, glides across the kitchen in roller skates and uses her pool noodle as a hockey stick to practice moves. Her bedroom wall is dotted with pictures of Edwards, her mother, Jessica Davis, said. The Davis family is not a hockey family, but Jessica Davis said her daughter wants to pursue the sport. She planned to take Kennedy to the community center to learn how to ice skate.

“I hope Laila knows how much an impact she is making,” Jessica Davis said.

Back at the New Heights Grill, the crowd is relishing the Americans’ dominance against Canada in the preliminary round, when — there goes Edwards up ice, cradling the puck on her stick. She crosses the blue line, dekes a defender and flicks her wrist.

Goal. Her first Olympic goal.

Cheers thundered across the arena in Milan, but they might have been louder at the New Heights Grill, where the men at Table One and the woman in the Heights hockey sweatshirt and the couple who changed their lunch plans clapped and whistled for Laila Edwards, the pride of Cleveland Heights.

Kitty Bennett contributed research.

The post ‘A Superstar Is From Here’: Pride of Cleveland Suburb Soars for U.S. Hockey appeared first on New York Times.