Roy Medvedev, the Soviet historian whose books on Stalin’s crimes and Communism’s excesses made him a political outcast for decades, and then a rehabilitated voice of conscience as an invalid Soviet Union stumbled toward collapse, died on Friday. He was 100.

His daughter-in-law Svetlana Medvedeva confirmed the death to the Russian state news agency Tass and said the apparent cause was heart failure.

In the palindromic world of Soviet-speak, where things proclaimed false were often real and things proclaimed real were often false, Mr. Medvedev was an internationally known nonperson — a Marxist writer of power and insight who did not change his socialist democratic message, but came full circle, from villain to hero, as history turned around him.

Taken together, his score of books and hundreds of essays became the story of the Soviet era from 1917 to 1991, documenting Stalinist executions that mounted into the millions; Communist dictatorships that imposed sweeping repressions, censorship and state controls over ordinary lives; and the transition under Mikhail S. Gorbachev and Boris N. Yeltsin to post-Soviet Russia.

In the West, he was known as the most independent historian of the era. His major works, including his best-known book, “Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism” (1971), were published abroad, but circulated underground at home under the radar of censorship.

Unlike other Soviet dissident writers, including his twin brother, Zhores A. Medvedev, who died in London in 2018, and the Nobel Prize-winning author Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, who died near Moscow in 2008, Roy Medvedev managed to avoid imprisonment and forced exile.

But for 20 years after his calls for democratic reforms first appeared in samizdat (clandestine) journals in the mid-1960s, he was persona non grata. The authorities subjected him to house arrest, ransacked his apartment, seized his research, accused him of slandering the nation and expelled him from the Communist Party. Still, he remained loyal to the party and the nation and insisted that changes must come from within.

He was right, eventually. Mr. Gorbachev became the Soviet leader in 1985 and instituted glasnost (openness), perestroika (restructuring) and reforms that included a modest relaxation of censorship, restraints on the police, multicandidate elections and a new legislature of people’s representatives. Some writers who had been denounced as traitors were praised, and many exiles, including Mr. Solzhenitsyn, who had spent almost two decades in the United States, were allowed to return home.

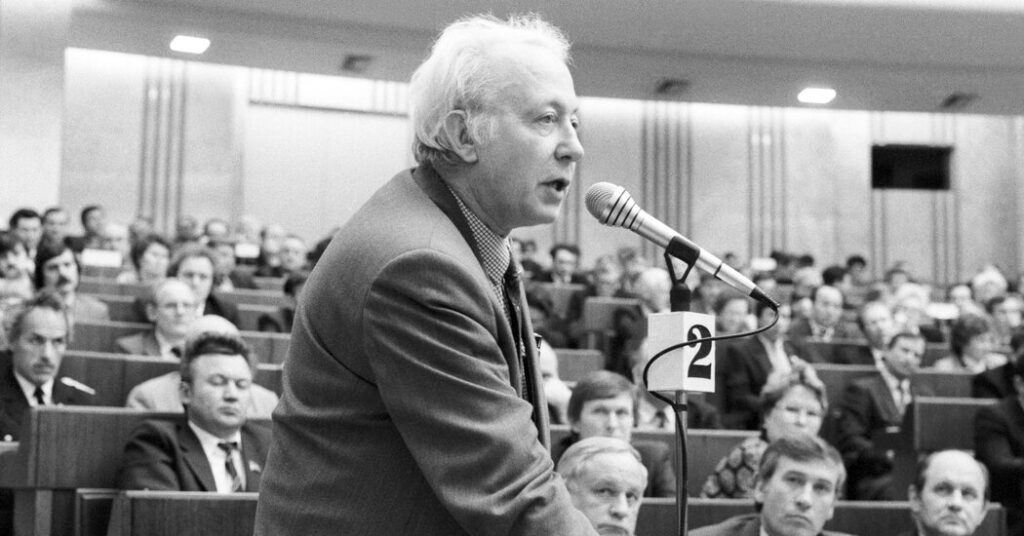

In 1989, Mr. Medvedev was reinstated by the Communist Party, elected to the Congress of People’s Deputies and elevated to prominence as a social and political critic. A year later, he became a member of the party’s Central Committee, the ruling elite that had scorned him. “I didn’t change my views,” he said at the time. “A turnabout occurred in the party, the Central Committee. They stopped discriminating against me.”

By then, there had even been calls for unbanning his books. The Communist youth weekly Sobesednik in 1988 portrayed him as an old hero. “We hope that soon the Soviet reader can also become acquainted with the works of our unyielding countryman, Roy Medvedev — sharp, polemical, controversial, appealing to the voice of conscience in each of us, surprisingly true and sincere,” it said. “The times demand these books.”

In his rumpled jacket with collar undone and necktie askew, Mr. Medvedev looked like a gentle professor. He was calm and soft-spoken, with lidded blue eyes and a shock of white hair scraped back from a high forehead. The face was a bit red, as if he’d just had a bottle of wine, and he seemed perpetually on the verge of a wicked thought or a great idea.

Accounting of Atrocities

Restored to respectability, Mr. Medvedev in 1989 published the most detailed accounting of Stalinist atrocities ever presented to a mass audience in the Soviet Union, writing in the national weekly Argumenti i Fakti (circulation 20 million) that 20 million people had died in labor camps, forced collectivization, famine and executions, and that 40 million had been arrested, driven from their lands or blacklisted.

In 1990, “Time of Change: An Insider’s View of Russia’s Transformation,” by Mr. Medvedev and Giulietto Chiesa, the Moscow correspondent of the Italian Communist newspaper L’Unità, detailed Mr. Gorbachev’s tenure in a nation battered by economic problems, crime and ethnic conflicts, and moving toward collapse even as Mr. Yeltsin began to emerge as his successor.

Mr. Medvedev became a consultant to Mr. Gorbachev and Mr. Yeltsin and, over the next decade, he wrote political biographies of the Soviet leaders Leonid I. Brezhnev and Yuri V. Andropov, and volumes on capitalism and politics in post-Soviet Russia as well as on Vladimir Putin, who succeeded Mr. Yeltsin as president.

That book, sometimes translated as “Putin’s Time?,” appeared in 2002 and was soon on sale in the Kremlin bookshop. It detailed Mr. Putin’s K.G.B. work and the early stages of his rise to power and painted him, as he said in an interview at the time, as part of a “sober and pragmatic” generation born after World War II.

The work’s hopeful portrait — of a leader with “character and intellect” — came too soon to document Mr. Putin’s suppression of Russian democracy and political opponents, his war in Chechnya, annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine, which drew international economic sanctions and condemnation.

Roy Aleksandrovich Medvedev (pronounced Mid-VADE-yeff) and his identical twin, Zhores, were born on Nov. 14, 1925, in Tbilisi, the capital of Soviet Georgia.

Their father, Aleksandr Romanovich Medvedev, a Red Army political commissar in the civil war that followed the 1917 Revolution and later a professor of Marxist philosophy at Leningrad State University, was arrested in Stalin’s purges in 1938 and died in a Siberian labor camp in 1941. Their mother, the former Yulia Isaakovna Reiman, was a cellist from a Jewish family in Leningrad.

After Red Army service in World War II, Roy received a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Leningrad State University in 1951 and a doctorate from the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences in Moscow in 1958. Between degrees, he taught history at a high school in Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg) and was principal of a high school near Leningrad (St. Petersburg).

In 1956, he married Galina A. Gaidina, a physiologist. They had a son, Aleksandr. A list of his immediate survivors was not immediately available.

The same year Mr. Medvedev married — three years after Stalin’s death — he and his brother were successful in rehabilitating their father’s standing in the Communist Party.

“The fact that my father was arrested was something frightening and completely incomprehensible, completely out of accord with the ideas of Leninism or Marxism or socialism,” Roy Medvedev later said. “I understood that our lives had been visited by a great evil, but the extent of that evil I could not then understand. But I wanted to figure it out even then, so I decided in my earliest years to busy myself with politics, with social science, to examine what is good and what is bad in our society.”

In the late 1950s, Mr. Medvedev was deputy editor of the Publishing House of Pedagogical Literature in Moscow. In the 1960s, he was a researcher at the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences and, in 1970-71, was a senior social scientist. Zhores became a biologist and wrote books on aging, heredity and other subjects.

The brothers joined the Communist Party in the 1950s, but in 1961 they began writing major books that would be published abroad and circulated in samizdat at home, and would shape their destinies — Zhores from exile in London and Roy from a fifth-floor walk-up in Moscow, each writing a canon of dissent that eventually became, more or less, politically correct.

Zhores’s 1969 book, “The Rise and Fall of T.D. Lysenko,” attacked the pseudoscience of Stalin’s director of biology, whose unscientific theories corrupted Soviet sciences, contributed to disastrous crop failures and led to the banishment and death of uncounted opponents. In the 1970s, Zhores was arrested, declared insane, confined in a mental institution and later stripped of his citizenship while working in London.

Meanwhile, Roy’s landmark book, “Let History Judge,” documented as never before the staggering crimes of Josef Stalin, who ruled from 1928 until his death in 1953. It was based on party archives dating to 1917, affidavits of concentration camp survivors, memos of victims retrieved posthumously, and reports by a commission that after Stalin’s death investigated his mass purges and accounts by hundreds of witnesses.

Mr. Medvedev concluded that Stalin was not a madman, but was a paranoid obsessed with power who became an evil force that corrupted Communism. Avoiding another Stalin was critical to a socialist democratic future in the Soviet Union, he insisted. These were divisive judgments inside the Soviet apparatus and in a world that had often compared Stalin to Hitler and regarded Soviet Communism as irretrievably befouled.

Despite Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization speech before a party congress in 1956 and later investigations that exposed many Stalinist crimes, censors rejected Mr. Medvedev’s book twice in the 1960s, wavering in an uncertain Orwellian climate that acknowledged Stalin’s misdeeds, but sought to de-emphasize them in order to resurrect him as a monumental, if flawed, leader.

When the book was published in New York in 1971, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Harrison E. Salisbury, in a review for The New York Times, hailed it as a milestone. “On the basis of Medvedev’s work,” he wrote, “every history of Russia from Lenin’s death to Khrushchev’s fall will have to be revised.” Edward Crankshaw, a journalist, author and authority on Soviet politics, wrote in the British newspaper The Observer that the book was “nothing less than a one-man attempt to rescue the history of the Soviet Union from the party hacks and to salvage the honor of the revolution.”

Acts of Defiance

During the book’s years in limbo, from 1964 to 1971, Mr. Medvedev and his brother produced 79 issues of an underground monthly, Political Diary, which discussed censorship, socialist democracy and other subjects.

They also wrote “A Question of Madness,” on Zhores’s 19 days in a mental institution and the protests that won his release. The book, charging that 250 people were held in Soviet mental asylums for political reasons, appeared in London and New York in 1971 and generated international shock waves.

In addition, Roy Medvedev and Andrei D. Sakharov, the nuclear physicist who later won the Nobel Peace Prize, sent an open letter to the Kremlin analyzing failures of the Soviet system. These acts of defiance soon ended a period of relative freedom for Mr. Medvedev. Political Diary was closed, he quit the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences, his archives were raided and he went into hiding for a time.

In “On Socialist Democracy,” published in the United States in 1975, Mr. Medvedev identified himself with a small group of Communists who favored democratization of Soviet society, civil rights, free elections, a multiparty system and decentralized government. To advance these ideas, he founded an underground journal, Twentieth Century, in 1975. The authorities closed it after 10 issues.

But his books reached the West with drumbeat regularity: “Khrushchev: The Years in Power” (1976), with Zhores; “Problems in the Literary Biography of Mikhail Sholokhov” (1977); “Philip Mironov and the Russian Civil War” (1978), with Sergei Starikov; “The October Revolution” and “On Stalin and Stalinism” (both 1979); “Nikolai Bukharin: The Last Years” and “On Soviet Dissent” (both 1980); “Leninism and Western Socialism” (1981); “An End to Silence” (1982); “Khrushchev” (1983); and “All Stalin’s Men” (1984).

Roy and Zhores Medvedev often criticized what they regarded as abuses by the West, particularly in stockpiling nuclear armaments. In “A Nuclear Samizdat on America’s Arms Race,” published in The Nation in 1982, they condemned American Cold War attitudes as “primitive” and tending to “greatly oversimplify complex social and historical processes.” In 1983, Roy Medvedev accused President Ronald Reagan of bombast in calling the Soviet Union an “empire of evil.”

Western critics sometimes disagreed with Mr. Medvedev’s evaluations, and some said his hopes for a democratic Russia were pipe dreams. He was often accused of biases of selection and of playing loose with facts for the sake of an argument. His writing, though exhaustive, was not of great literary quality, some said, but the patient reader was rewarded with thorough research, an insider’s knowledge and insightful conclusions.

Although they did not see one another for many years, Roy and Zhores communicated frequently by mail and sometimes through intermediaries. They helped each other with projects, exchanged books and maintained a relationship that was at once scholarly, practical and familial.

The New Yorker editor David Remnick, then a Moscow correspondent for The Washington Post, noted in 1989 that the brothers each kept a picture of the other at hand and, above their respective desks in Moscow and London, photographs of their father as a handsome young Soviet military officer.

After the Soviet collapse, as Russia fragmented into a federation of republics and provinces, Roy Medvedev joined former Communist deputies and members of the Russian Parliament in founding the Socialist Party of Working People, one of many new political organizations. He became its co-chairman.

And in later years, he continued to write commentaries — about Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Khrushchev, Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and the long gray line of ghosts from the past.

Robert D. McFadden was a Times reporter for 63 years. In the last decade before his retirement in 2024 he wrote advance obituaries, which are prepared for notable people so they can be published quickly upon their deaths.

The post Roy Medvedev, Soviet Era Historian and Dissident, Is Dead at 100 appeared first on New York Times.