Got milk?

If you’d asked that question around Southern California even into the 1950s, the answer would have been a big full-dairy-fat “yes,” pails and gallons and maybe even acre-feet of milk.

As the 19th century turned into the 20th, hundreds of thousands of cows were living on hundreds of small dairy farms cast across the broad plain of what is now crowded with homes, streets, businesses and freeways.

Dutch, French, Portuguese and Belgian families each kept a few, a dozen, or a couple of hundred milk cows on land that’s now too expensive even to keep chickens. The Lescoulies’ cows were in Venice; a Mr. Martin kept his on Primrose Avenue in Hollywood, where the early farmhouse was lately priced at about $2 million.

These little farms sold their milk to dairies that bore wonderful names like Calla Lily, in Glendale, Golden Poppy, in Downey, Santa Monica Dairy, in Venice, and Baldy View dairy, in Whittier.

Within a few decades, in Southeast Los Angeles County, cows outnumbered people by as much as 30 to one. The place we now know as Cerritos was once named “Dairy Valley” and was home to not quite 3,500 people and 100,000 cows. The community we know as Cypress was, until 1956, called “Dairy City.”

A few of those dairy operations survive today.

Why bring our dairy history up now?

Because both President Donald J. Trump and his Health and Human Services secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., are on a dairy kick. They’ve stood the longtime food pyramid on its pointy head, instead promoting lots of meat and whole milk foods over a healthier diet grounded in whole grains and vegetables.

The U.S. Agriculture Department has posted an image of Trump leaning forward on his knuckles on the Oval Office desk, a belligerent look on his face and a milk mustache on his upper lip. RFK Jr.’s more genial video version shows him sipping a glass of milk and being dreamily transported to a lively dance floor.

Maybe it hardly matters to consumers whether the milk is skim or full-fat — the former with about half the calories per glass and of course none of the fat of the latter — but fat or skim, 1 in every 5 glasses of milk that’s drunk in this country comes from California dairy companies.

How did California do it? How did it snatch the crown from “America’s Dairyland,” the motto on the license plate of Wisconsin? The “Badger State” still holds the cheese-making champion title but lost the overall dairy edge in 1993, when California surpassed it as the milk-producing leader.

That PR campaign about the country’s top dairy title was brutal, and costly — $23 million on California’s end. The first punch was landed by the “Got Milk?” campaign from the California milk industry, with one 1993 TV commercial in particular.

It was directed by that Michael Bay, and in it, an Alexander Hamilton super-fan is eating a peanut butter sandwich when his phone rings. It’s a radio quiz show: for $10,000, who killed Alexander Hamilton? The fan shouts “Aaron Burr! Aaron Burr!” but his mouth is so stuck full of peanut butter that he’s unintelligible. He reaches for his carton of milk — it’s empty. The radio quiz caller finally says, “I’m sorry, maybe next time.” Cut to the screen message: “Got milk?”

Here’s how California did it. It’s not just California’s greater size, but its dairy practices. In Wisconsin, dairy farms are smaller, herds are smaller, and cows are usually sent out to pasture to graze in good weather, which is not easy to come by in Wisconsin. Not all Wisconsin cows are grass-fed, but grass-fed milk can have up to twice the beneficial Omega-3 fatty acids compared to milk from feedlot cows.

And feedlot cows are what California has. Dairying here quickly scaled up to an industrial level, like factory-grade milk production. Forget cows ambling in biodiverse pastures. Here, rather like the Chicago stockyards, thousands of dairy cows are fed in crowded feedlots by a method called intensive and dry-lot feeding, or, alternately, kept indoors in barns.

Feedlot cows are given a special blend of hay, alfalfa, soybean meal, sometimes almond hulls and even what we’d call leftovers — human candy and leftover baked goods.

These cows yield more milk but can be more susceptible to health problems. In August 1977, humidity and heat from a tropical storm was blamed for killing 725 dairy cows in Chino. Experts speculated that dry-lot cows can’t sweat as freely as free-range cows, and that weather and feedlot conditions contributed to deadly heat exhaustion.

It all began through the first decades of the 20th century, when good-sized pieces of land in southeast LA County could be had for not much money, and there was water for agriculture — Artesia was named for its artesian wells — and specifically crops to feed the cows.

Dairymen from the Netherlands and from the Portuguese Azores staged dairy festivals and competitions, and went to culturally based schools and churches. And they soon embraced mechanized milking and the feedlot model to up their yield.

The city of Paramount was incorporated in 1958 by folding together a pair of renowned dairy and hay communities named Hynes and Clearwater. In downtown Paramount, a five-story-tall tree bears state historical marker No. 1038. It’s the 130-year-old Hay Tree. Hynes bragged about being the “world’s largest hay market” whose prices were listed in New York, and jawed over and set daily by local farmers and hay growers who gathered under the branches of that camphor tree.

Still, in 1965, as agriculture of all kinds was being crowded out by subdivisions, California enacted the Williamson Act to give tax breaks to landowners who kept their property dedicated to agriculture.

Even that wasn’t incentive enough for some dairy farmers, whom developers were offering 10, 20, 50 times what they had paid for their land. Some sold up and left. Others, like German immigrant August Handorf, simply relocated — repeatedly.

As neighborhoods went up, his dairy business moved on: from Highland Park to Eagle Rock to the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Western Avenue — for a time in the 1920s and 1930s the busiest intersection in the nation. He moved his operation way out to Burbank, to land now occupied by Warner Bros. studios. And Handorf bought land near La Puente, which he forbade his family from selling. Not until he died, in 1955, was it sold off.

Alta Dena was founded by three Stueve brothers in Monrovia at the end of World War II, with 61 cows and a milk wagon. Now it’s owned by a dairy cooperative but for decades, the Stueve family catered to local tastes and habits, like drive-through dairy windows. The Stueve brothers always defended raw milk, as brother Melvin Stueve phrased it, “the very best and safest milk there is.”

Here in California, raw milk products are sold at higher-end markets, but must be labeled thus: “WARNING: Raw (unpasteurized) milk and raw milk dairy products may contain disease-causing microorganisms. Persons at highest risk of disease from these organisms include newborns and infants; the elderly; pregnant women; those taking corticosteroids, antibiotics or antacids; and those having chronic illnesses or other conditions that weaken their immunity.”

Still raw milk has a big-name poster guy in RFK Jr., who not only fancies whole milk but swears by raw milk and drank unpasteurized milk “shooters” at the White House. Soft cheeses made with such unpasteurized milk can run an infection risk from listeria bacteria, a special danger for pregnant women and newborns.

Earlier this month, a newborn baby died from a listeria infection in New Mexico after the infant’s mother drank raw milk, and officials there are warning people off those products while the death is being investigated.

In 1985, more than three dozen deaths in California — including stillbirths and fetuses lost to miscarriage – were blamed on listeriosis from soft cheeses produced by an Artesia company named Jalisco Mexican Products.

LA health investigators were convinced that both raw milk and unsanitary Jalisco processing were at fault, but in 1989 a jury blamed the listeriosis deaths exclusively on the cheese -maker and not the raw milk supplier, the Alta Dena Dairy.

A few Southern California’s early diaries survive, in an altered fashion, from their origins. Rockview Farms turns 100 next year, and in Downey still processes milk from elsewhere. The retro glass bottles from Broguiere’s plant in Montebello have a new fan base. The Scott Brothers’ plant in Chino processes dairy products from the family’s own sustainable acreage, as it has since 1913.

If you’d like to buy a bottle of milk from wherever it is that actor Robert Mitchum was milking that cow in 1948 — part of his sentence for feloniously smoking marijuana — you’re out of luck. The L.A. County sheriff’s department bought Castaic dairy farm in 1938 for its “honor farm,” where low-risk prisoners like Mitchum worked the farm as they served their sentences. The farm operations were closed in 1992.

The drollest dairy origin story belongs to Rhoda Rindge Adamson. In 1892, her parents, Frederick and May Rindge, bought up an unimaginably enormous tract of land — 25 miles of Pacific coastline along Malibu and beyond. Rhoda loved the ranch life, but especially cows. She spent just one homesick year at Wellesley College, where the walls of her rooms at Wellesley were covered with pictures of cows.

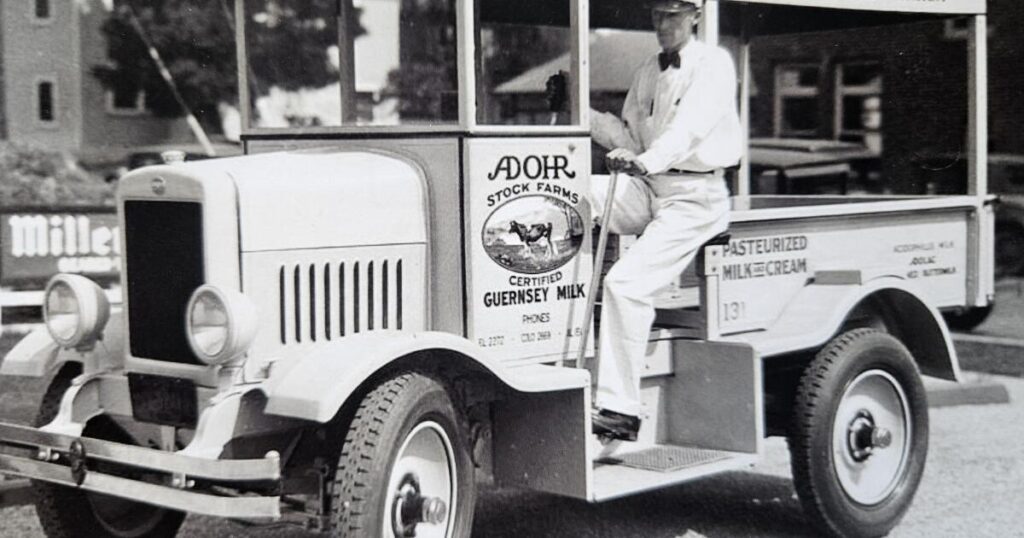

And after she came back to California and got married, she and her husband, the Rindge ranch foreman, started up a Guernsey milk business that became one of the biggest dairy operations in the world. You’ll no longer find it in grocery refrigerators, but you may remember its name — Adohr, which is “Rhoda” spelled backward.

Ask the question “Got milk” these days and the answer may be “Yeah, but what kind?” Vegans and vegetarians have popularized plant-based milk alternatives — almond milk, oat milk, soy milk, cashew, hemp, coconut; if it grows, it may have a milk version. But even in California, dairy milk still rules the roost, and every year for nearly 70 years, the California Milk Advisory Board has crowned its California Dairy Princess as its dairy ambassador.

One year, I covered the event, and the question I put to one official was the obvious one: why just a dairy princess?

Because, he told me, “There is only one queen in the dairy business, and that is the cow.”

The post How SoCal became the nation’s dairy queen appeared first on Los Angeles Times.