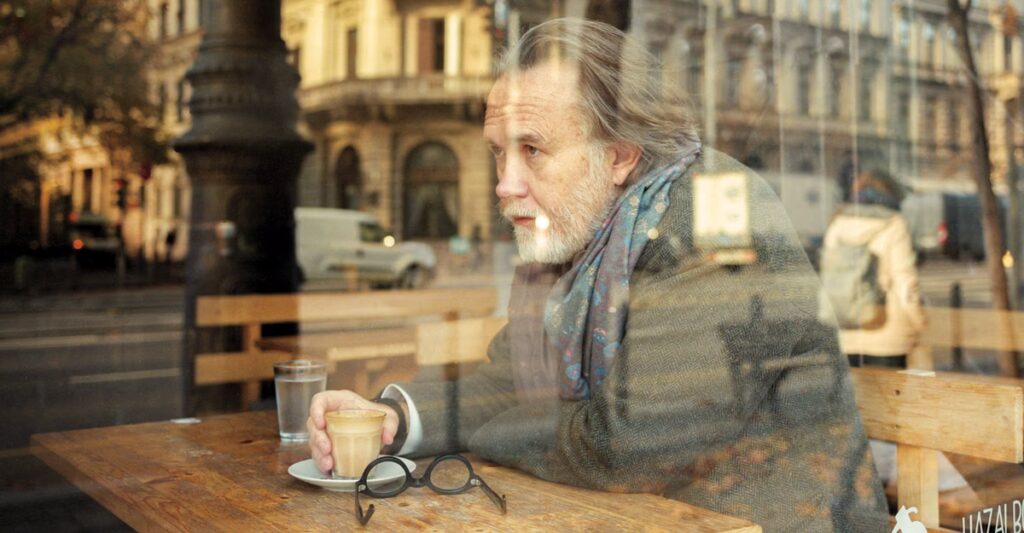

Photographs by Erika Nina Suárez

On an April evening last year, Rod Dreher sat in the front row of an auditorium at the Heritage Foundation, in Washington, D.C., giddy with pride and happiness. He was there for the screening of a new documentary series based on one of his books, Live Not by Lies, about Christian dissidents from the former Soviet bloc—but first, a special guest was making his way toward the stage. J. D. Vance arrived at the podium to a roar of applause and told the crowd that he would not be the vice president of the United States if not for his friend Rod.

It was Dreher, Vance said, who latched on to his memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, a decade ago and promoted it on his blog for The American Conservative, helping to vault the book to the best-seller list. Dreher then became a friend and adviser to Vance as he launched his political career. After praising Dreher for 10 minutes, Vance invited him onstage. The two men hugged, each of them saying, “I love you, man.”

Unlike many in the crowd, Dreher, then 58, was not a staunch Donald Trump supporter; he had long criticized the president and came around only at the beginning of his second term, after concluding that Trump’s crude energy was needed to defeat progressive ideas. But Dreher has been giving voice to the yearnings and frustrations of religious conservatives for many years—as a magazine blogger with more than 1 million pageviews a month, an author of best-selling books, and a deliriously verbose writer on Substack. In January he joined The Free Press as a regular contributor. More than anyone else I know of, Dreher offers a full-fledged portrait of the cultural despair that haunts our era, a despair that has helped pave a road toward tyranny.

Dreher emerged from the conservative blogosphere in the 2000s and won fans with his daily stream of testy opinions and unguarded anecdotal writing. He seems almost allergic to ideological consistency, has long had readers on the left as well as the right, and sometimes changes his mind over the course of a single paragraph. He can be mean-spirited at times, but is quick with a heartfelt apology when he thinks he has made a mistake. His columns are often a collage of quotes from the day’s news and from an eclectic cast of literary and philosophical idols: Dante, perhaps, or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, or the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre.

When Dreher became a prominent figure a decade ago, he seemed resigned to the idea that religious conservatives like him had lost the political battle. In The Benedict Option—the 2017 book that put him on the map—he counseled a patiently monastic approach to Christians who felt that their faith was endangered in a relentlessly secularizing era. Drawing inspiration from Saint Benedict of Nursia, who founded thriving monasteries in the sixth century as Rome decayed, he wrote of a future in which committed Christians “will have to be somewhat cut off from mainstream society for the sake of holding on to the truth.”

[From the January/February 2020 issue: Emma Green on the Christian withdrawal experiment]

But over the past decade, the rightward shift of politics has made clear that Dreher’s intuitions are more widely shared than he once thought. Take his interest in the supernatural and the demonic, the theme of his latest book, Living in Wonder. “The world is not what we think it is,” Dreher writes. “It is so much weirder.” We must disavow our scientific materialism and learn “to open our eyes to the reality of the world of spirit and how it interacts with matter.”

Such ideas appear to have fueled some of the more apocalyptic currents on the Trumpist right, such as Peter Thiel’s musings on the anti-Christ and the ravings of Dan Bongino, the former deputy director of the FBI, who has said that demons are real. Before Tucker Carlson went public in 2024 with his story about being attacked in bed by a demon, he confided in Dreher.

I first began reading Dreher’s Substack a couple of years ago and felt as if I’d stepped into another world. Dreher spends much of his time with monks, back-to-the-land theologians, and exorcists. He believes that a great spiritual battle is under way: “As faith has receded, and interest in the occult and pornography has grown, so has demonic activity.” He continues, “Priests must understand that they are dealing with discarnate beings—fallen angels—who are vastly more intelligent than mortals.” Dreher often speaks of AI as a portal to the demonic, and he feels similarly about the trans-rights movement, which he sees as a symptom of a progressive dystopia in which there are no “structures of truth outside the choosing self.”

To a secular ear, all of this supernatural talk can sound like useful idiocy that serves only the autocrats Dreher sometimes praises—people such as Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s authoritarian leader, who are always in need of a crisis, spiritual or otherwise, to justify their most extreme measures. Dreher moved to Budapest in 2022 and is on familiar terms with Orbán and other European conservatives.

[From the May 2025 issue: Anne Applebaum on how America’s future is Hungary]

But if Dreher is any sort of courtier—a suggestion he would angrily reject—he is entirely sincere in his beliefs, and his deepest concerns are more religious than political. He seems tempted by the idea that Trump’s wrecking ball could clear the ground for a cultural rebirth. “I had never been enthusiastic about Trump,” Dreher told me, “but I was enthusiastic about him this time because it seemed like only somebody like him could put a stop” to “wokeness and the madness of transgenderism.”

Dreher’s writing is a useful indication of just how angry and pessimistic even the most thoughtful conservatives have become in recent years. He seems to see America as a hellscape, drained of religion and hope, drugged and distracted by the false gods of the internet. The renewal he imagines is not the sunlit, future-oriented conservatism of the Reagan era, and he doesn’t look to the Founding Fathers for inspiration. If anything, Dreher’s compass points in the opposite direction. He wants his country to turn back toward Europe—not the homogenized, secular continent of today but premodern Christian Europe, before the Enlightenment and the disenchantment set in.

I met up with Dreher in early June outside the Church of Saint-Sulpice, in Paris. We were surrounded by thousands of excited young Catholics preparing for the start of an annual pilgrimage from Paris to Chartres, organized by devotees of the traditional Latin Mass. The pilgrimage is a rallying point for conservative Christians from across Europe and beyond; Catholic political figures sometimes join the pilgrims for a stretch.

“This is my world but not my world,” Dreher told me as we ambled through the crowd. He meant that he is Christian and conservative, but no longer Catholic. He left the faith 20 years ago, disgusted by the Church’s handling of the sex-abuse scandal, and became an Eastern Orthodox Christian. But he still feels an affinity with Catholics, especially the theological conservatives who adhere to the Latin liturgy that was universal in the Church until the Vatican II reforms of the 1960s.

“I can’t think of the last time I felt so happy,” Dreher said, in a drawl that evokes his Louisiana origins. His joy was partly a measure of his long-running preoccupation with the future of Europe, where the broader culture has been steadily marching away from Christianity. Fewer than a quarter of French people ages 18 to 23 identify as Catholic. The continent’s eroding religious traditions and cultural loyalties, and its surging population of Muslim migrants, are a constant and gloomy obsession in Dreher’s posts. But here, surrounded on this morning by Christian pilgrims, he felt sparks of hope.

A Mass began inside the church, and loudspeakers broadcast the sounds of a choir to the overflow audience outside. All talk ceased, and thousands of people crossed themselves and knelt on the pavement. It was a very different Paris from the one most tourists or even Parisians see.

Dreher’s excitement about the pilgrims turned out to be mutual. A number of them rushed up to greet him as the journey began. His work has gained a following in France, especially among young people who grew up in a thoroughly secularized Europe and are hungry for a more traditional or mystical experience. “Rod allowed the French to pose the question of faith in a new way,” Yrieix Denis, a 34-year-old Catholic writer and consultant who helped get The Benedict Option published in French, told me. Dreher’s perspective was refreshing, Denis said, because he had no stake in the political arguments that consumed and divided older French Catholics; he just wanted to help people sustain their faith in a hostile climate. And his warnings about demons lurking in our cellphones and laptops seem to resonate with the younger generation.

Dreher’s ideas about the decline of Christianity in Europe—once seen as a little conspiratorial—are now becoming something like the official view of the Trump administration. When Vance attended the annual Munich Security Conference as a first-term senator, in 2024, he got fed up with the European Union bureaucrats and took off early to reconnect with Dreher, who had come from Budapest, over beer and sausages. A year later, Vance returned to Munich as vice president and vented his feelings about the arrogance of Europe’s ruling elite and the dangers of mass immigration in a speech that could almost have been written by Dreher, accusing the European leaders seated before him of betraying their own civilization. Those themes were echoed in December, when the Trump administration released a new National Security Strategy warning that Europe was in danger of “civilizational erasure.”

The pilgrims marched westward out of the city, carrying crucifixes and flags bearing the names of local saints. They would be camping outdoors for two nights on their way to Chartres, but Dreher would not be joining them. “I’m a crotchety old bastard who won’t camp,” he’d told me.

Dreher’s phone lit up often as we strolled through the newly empty streets toward the Latin Quarter. He presents a peculiar blend of gregariousness and inner solitude—connected to many people around the world yet profoundly lonely. His marriage broke up years ago, and he is now mostly estranged from his former wife and two of his three children. He lives alone in Budapest.

His daily routine, Dreher told me, is a trip to a local café followed by hours of reading and writing. Later he will walk around the city, his only form of exercise, and perhaps meet friends for drinks or dinner. During the five days I spent with him in France, he wrote and published four online columns, each several thousand words long. When I expressed surprise at his output, he said: “It’s all I do.”

Dreher didn’t shy away from questions about his belief in the supernatural. He told me that he had once seen a woman possessed by demons while he was visiting her and her husband at their Upper East Side apartment, a story he recounts in Living in Wonder. The demons weren’t themselves visible: One of them shouted obscenities through the woman’s mouth, the way a demon possessed Linda Blair’s character in The Exorcist, until her husband managed to silence it with a “relic of the True Cross” hidden in his pocket. The woman apologized for the demon’s outburst, saying, “That wasn’t me.”

Dreher rattled off other encounters he’s had with poltergeists and various nameless spirits. At the same time, he made clear that he wasn’t sure how real these experiences were or what they meant, and noted that this was precisely the point: We should not remain “locked in an iron cage of scientism and rationality.”

I got the sense that, for Dreher, the demonic is partly a metaphor, a way of talking about the psychic disturbances of our age. At his best, he is capable of shedding light on these disturbances, and not in narrowly religious terms. Dreher has a gift for articulating the unease that many people, including thinkers on the left, feel about the rapid erosion of borders and traditions of all kinds and the birth of an online landscape that seems to promise infinite autonomy but is in fact a “vast disenchantment machine.”

To Dreher, these changes are not just the queasy side effects of a world that is shedding outworn rules and becoming freer. They represent the fraying of a social and cultural order built on Christianity, and are responsible for a litany of troubling symptoms: loneliness, rising rates of anxiety, political polarization. “If you wanted to create a society and a culture that’s guaranteed to make people miserable,” Dreher told me, citing the psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, “you couldn’t do better than what we’re living in now.” Dreher often invokes the experience of fourth-century Romans, who could not see that the ageless pagan world they’d inherited was at an end, and that they were on the verge of a radically new and less stable era.

In recent years, Dreher’s premonitions have caught on with a number of secular-minded people who have concluded that the West needs Christianity to protect it from an array of perceived threats, including the spread of Islam. Some, such as the Somali-born author and former atheist Ayaan Hirsi Ali and the British comedian Russell Brand, have converted to Christianity. Others, such as Jordan Peterson and Joe Rogan, seem ambivalent or opportunistic. (Rogan said in 2024 that, “as time rolls on, people are going to understand the need to have some sort of divine structure to things.”) Perhaps Dreher’s most surprising ally is the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, the author of The God Delusion and other atheistic broadsides, who has declared that he is now a “cultural Christian.”

But lately Dreher’s insights have come with an ominous political corollary. He believes our institutions are so rotten that they need a good slap from people like Trump and Orbán, even if it means losing some of them. “Maybe what’s being born now will be worse, I dunno,” he wrote as Trump and Elon Musk were using DOGE to dismantle the federal bureaucracy in early 2025. “We’ll see. But bring it on. I’ve had it.”

Dreher didn’t always talk this way. In early 2017, he told an audience at the National Press Club that Trump’s election suggested a weakness in the faith of the many Christians who had voted for him. Trump was another symptom of a “consumerist, individualistic, post-Christian society that worships the self.” The writer Andrew Sullivan, who has been a friend and occasional sparring partner of Dreher’s for decades, told me he believes Dreher hasn’t really changed. “The politics came to him more than the other way around,” Sullivan said, suggesting that Dreher was radicalized by his opposition to the trans-rights movement, Black Lives Matter, and other progressive causes.

The past decade may have been a very successful one for Dreher—he published three books and gained a much wider following—but it has also been a time of deep suffering, as anyone who reads his posts knows. His family broke apart in multiple ways, culminating in a divorce that took a terrible toll and left him almost entirely alone. When I first met Dreher, over dinner at a Sichuan restaurant in New York in April, he looked careworn, with signs of fatigue around the eyes. I couldn’t help wondering whether Dreher’s diagnosis of a “civilizational crisis,” demons and all, was partly a measure of his own emotional turmoil.

The story of Dreher’s personal Calvary begins with his father, who seems to be the key to his lifelong struggle to get closer to God. Ray Dreher was a rural public-health officer and a stubborn authoritarian who expected his children to spend their life in the Louisiana town of St. Francisville (population 1,557), where they grew up. Rod, his only son, loved books and dreamed from an early age of getting away to Europe. As an adolescent, he scorned the narrowness of his parents’ lives, their views (Ray appears to have been a member of the Ku Klux Klan), and their bland Methodism—“Christianity as psychological and social wallpaper,” as Dreher put it to me. He got out as soon as he could, going to college at Louisiana State University and then moving to the East Coast. His father never really forgave him for it.

Dreher traveled far from St. Francisville over the following decades, as an inner restlessness led from one religious incarnation to another. He started off as a secular liberal, but in his mid-20s he felt drawn back to faith, thanks in part to a one-night stand that led to a brief pregnancy scare. He converted to Catholicism at the age of 26 in St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington, D.C. In 2006, he found a new home in Eastern Orthodoxy, an even more tradition-bound branch of Christianity.

In 2011, as Dreher was building a national reputation as a columnist, he decided to move back to St. Francisville with his wife and children. He had gained a new appreciation for his hometown after his younger sister, Ruthie, was diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer. Dreher was living in Philadelphia at the time, and during visits back home, he discovered that she had become a kind of local saint, revered for her charity and love of God. Ruthie’s funeral—which he described in a long post forThe American Conservative and later in a book, The Little Way of Ruthie Leming—brought out a deep sense of community. The love he saw there, he wrote, was “a thing of such intense beauty it’s hard to look upon it and hold yourself together.” Dreher wanted to be part of it, and to reconcile with his father.

The return was a spectacular failure. His father refused to relinquish his grudge, as Dreher saw it, and his mother always went along with her husband. Dreher told me the rift wounded him so badly that, for four years, he was mostly bedridden with chronic mononucleosis, sleeping four to six hours in the middle of the day. “The thing that I wanted more than anything else in the world,” Dreher wrote years later, “and have wanted from the time I was a little boy, is to feel at Home in this world, with a father who approves of me. That was not to be mine, except, by God’s grace, in heaven.”

He stayed in Louisiana for more than a decade, struggling to maintain a marriage that was failing for reasons that Dreher has never fully spelled out (he says he needs to respect his family’s privacy). Dreher says that only his faith in God sustained him. His writing about all of this is some of his best and most vulnerable. “It feels like that sometimes, that God has forgotten me, has forgotten us men who wanted to be good husbands and good fathers,” he wrote in 2023. “Flannery O’Connor has a character who says she thinks she might be able to be a martyr if they kill her quick. Yeah, me too. But the very slow martyrdom of the woman who bled out for twelve years, and for men and women who suffer the pains of marriages gone bad, and divorce—that’s harder, I think.”

In Paris, we skirted the edge of the Luxembourg Gardens, and the stony gray dome of the Panthéon became visible ahead. “I hate the Panthéon,” Dreher said. For a moment, I was baffled, but Dreher explained: The building where France inters its greatest patriots and public figures is an emblem of the secular faith that spread after the French Revolution, a reminder that the rot in contemporary Europe, as he sees it, goes back to the ideals of the Enlightenment—liberty, scientific inquiry, individualism.

He began talking about the revolutionary mobs of 1793 as if they had swept through yesterday. “Genevieve had always been the city’s local saint,” he said. “But the mob came and took her relics and burned them.” Dreher led me to the Church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, not far away, which contains what is left of her tomb. As we entered the dim sanctuary, he crossed himself and knelt to touch the floor in deference, an Orthodox tradition. We made our way to the chapel devoted to Saint Genevieve, where Dreher lit a candle for her, kneeled, and prayed.

Dreher can give the impression that it has all been downhill for humanity since the 14th century. In his writing, he offers a potted history of how we fell away from a luminous medieval wholeness, when sacred and secular were as one; when, as he has written, “the entire universe was woven into God’s own Being.” Dreher is well aware that this reactionary outlook strikes many people as ludicrous. He often refers to himself in his columns as “Your Working Boy,” a winking allusion to the half-mad protagonist of John Kennedy Toole’s 1980 comic novel, A Confederacy of Dunces. That character, Ignatius J. Reilly, is a grotesque, obese shut-in who reveres the sixth-century Roman philosopher Boethius and claims to be writing a “lengthy indictment against our century.”

I hear an echo of Ignatius Reilly when Dreher inveighs, as he often does, against progressive orthodoxy, writing incendiary posts with titles such as “Another Day, Another Killer Tranny.” When he champions “normie” values and sensibilities against the “soft totalitarianism” of wokeness, he seems closest to the aggrieved ethos of the MAGA base.

But I saw little evidence of Ignatius Reilly during my time with Dreher. He did not seem motivated by hatred or bitterness but instead came off as kind and humble, with an endearing habit of telling humiliating stories about himself. He seemed almost eager to have his own views challenged, and genuinely saddened by the loss of some of his friendships with liberals in recent years.

When Dreher wrote The Benedict Option, during the Obama presidency, his primary concern was how to keep faith alive at a time when Christianity seemed to be fading away. After it was published, his ideas took a darker turn: The portal to the demonic was getting larger, and Western civilization itself was at risk. Dreher told me he often meets ordinary Europeans who believe that civil conflict is just around the corner. There are certainly people who feel that way, but reading Dreher, it’s hard to avoid the sense that he wants a civilizational crack-up, a cleansing storm that would chase away evil forces and allow for Christian renewal.

This kind of talk has political consequences. How far is he willing to go? Dreher told me firmly that he could never condone a religious belief being forced on anyone, and he has regularly said in his columns that he opposes a totalitarianism of the right as much as one of the left. He told me that authentic Christianity “can’t exist if liberal democracy goes away.” Dreher has written some scathing things in recent months about Trump’s tariffs and his overall fecklessness, and has lost Substack subscribers as a result, he said.

Dreher has also spoken out forcefully against the rise of anti-Semitism and the white-nationalist trolls in the MAGA base known as “Groypers.” In November, he warned Vance about the trend during a visit to Washington. After Dreher criticized Tucker Carlson for hosting the Hitler-loving commentator Nick Fuentes on his podcast, Dreher revealed that Carlson had written to him privately to attack him and that their friendship appeared to be over.

But Dreher has also given plenty of rhetorical support to Trump’s demolition agenda. In February 2025, he wrote: “The System is collapsing? Good. It’s about time.” He hopes for a similarly bold assault on the liberal governments of Western Europe; he would like to see its white, native-born population rise up and fight against the dilution of its Christian heritage. In July, he wrote a melancholy post asking why the British are “acquiescing in their own demise as a people.”

[Read: Make America Hungary again]

And then there is Dreher’s decision to move to Budapest. I asked him about the price of Orbán’s rule—the shameless undermining of democratic institutions, the rampant corruption, the weak economy, the kowtowing to Vladimir Putin. Dreher told me he doesn’t support everything Orbán has done, but he was full of praise for the Hungarian leader, whom he credits with having rescued his country’s social and cultural integrity by limiting immigration. “The man is a real visionary,” Dreher told me. The two have met only three or four times, he said, but Dreher has been affiliated since 2021 with the Danube Institute, a state-backed think tank that has been a vehicle for disseminating Orbán’s political ideas.

Dreher used his ties with Orbán to help Carlson get an interview, which aired in August 2021. After Carlson gushed about Orbán’s avowedly illiberal approach to governance, American conservatives began making regular visits to Budapest, and references to “the Hungarian model” became a standard feature of Trumpian politics. Dreher bears a share of responsibility for all of this.

After two days of hiking, the pilgrims arrived in Chartres looking sweaty and exultant. Dreher was there to greet them, after an hour-long train ride from Paris. We entered the sanctuary, with its cool scent of ancient stone. Dreher led me to a spot at the center of the nave and gazed down. This, he told me, was the exact stone on which he’d been standing when he had his first true religious experience, at the age of 17. His mother had won a round-trip ticket to Paris at a church raffle back in Louisiana, and she passed it on to him. Young Rod went off to France by himself, and on a visit to Chartres, standing in the nave of the cathedral, he was overcome by a vague but powerful sense that God was real.

Dreher has always sought solace in places that are rooted in tradition and far removed from modern life: hermetic religious communities, island monasteries, European cathedrals. His greatest admiration is reserved for people who commit themselves to “a fixed place and way of life,” as he wrote about Saint Benedict.

Yet Dreher seems resigned to living as a rootless exile, shorn of his family and condemned to wander a landscape of what the philosopher Zygmunt Bauman—one of Dreher’s favorite thinkers—called “liquid modernity.” I sometimes got the sense that all of his pilgrimages amounted to failed efforts to recapture the Edenic solidity of St. Francisville.

I accompanied him on another of these journeys after the Chartres pilgrimage. This one brought us to Rocamadour, a magnificent medieval town in Occitania, set on a cliffside above a tributary of the Dordogne River. Dreher had wanted to see the medieval chapel of Notre-Dame de Rocamadour for years, and for a curious reason: It is the site of a crucial scene in Michel Houellebecq’s controversial 2015 novel, Submission, in which the protagonist makes a failed attempt at religious conversion. The novel portrays France as a place so spiritually exhausted that it gives in to Islamic rule without much of a fight. Houellebecq is a famously cynical figure, and an odd bedfellow for Dreher. But the story made a deep impression on him.

We climbed the old stone steps toward the chapel. Above one entryway, a sword is lodged in the stone, said to have found its place there in the eighth century after being thrown more than 100 miles by Roland, the hero of the medieval chanson that bears his name. (This sword was actually a replica. A year earlier, the original had been stolen.)

The sanctuary was dark and silent. On the far wall, framed by a red-and-gold Gothic arch, was the Black Virgin, a doll-like wooden figure that pilgrims come to see. It is here that Houellebecq’s antihero, François, feels the stirrings of something divine. But the feeling fades, and he dismisses it as an effect of hypoglycemia and goes home. Dreher knelt in one of the pews and prayed.

He told me later that he’d been drawn to Houellebecq’s novel because of “what it says about the disposition one needs toward mystical experiences.” Many people, he said, lack the courage to act on their spiritual intuitions. Dreher himself may still be poised between belief and unbelief, struggling to break through the boundaries of the secular world he lives in. “Sometimes I ask, Am I fooling myself ? ” he told me at one point. But when he sees something like the Chartres pilgrimage, “I know I’m onto something.”

Late that afternoon, we got in the car and drove away. The route took us along rural roads with views of sun-gilded fields and hillsides. Dreher fell into a pensive mood. I asked him what lessons these holy places might hold for America. He said he wasn’t sure. But the question led us back to his friendship with Vance, and he recounted a strange dream he’d had the night before: “I was supposed to marry Arianna Huffington,” he said, “and J.D. was supposed to marry the girl I had a crush on in high school, but couldn’t have. I arranged things so that we switched brides. But then I was exposed and felt humiliated.”

To me, the dream suggested that Dreher sees Vance as a kind of secret sharer, as well as a possible vehicle for the mysteries he was chasing among the monks and pilgrims. Vance is the kind of figure who might help create the conditions for a reenchantment of American life, or so Dreher hopes. “That man is the future of America,” Dreher wrote in April. If Trump represents Armageddon, Vance for Dreher may be something like the Rapture.

After the 2024 election, a number of people urged Dreher to move to Washington, saying he could capitalize on his friendship with Vance and double his readership. I sensed that Dreher had considered the idea, however briefly. Were Vance to become president, the temptation to return would be even stronger. Dreher might be offered honors, or unique access to the administration as a writer. Would he seize the chance?

He told me he would not. He is more useful to Vance at a distance, he said. In any case, he is not looking for a political messiah. He wants the real thing.

This article appears in the March 2026 print edition with the headline “Rod Dreher’s Demons.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

The post Rod Dreher Thinks the Enlightenment Was a Mistake appeared first on The Atlantic.