In the spring of 2013, I was a sophomore at Tufts University in Massachusetts, soon to declare a dual major in international relations and Mandarin Chinese.

Despite my lofty aspirations to travel the world as a diplomat, my academic career so far had taken me a whopping 25 miles north of my hometown. That’s why my university’s study abroad program in China appealed to me.

Once I heard the tales of adventure from the 2012 program’s freshly minted graduates, I eagerly applied. That summer, with an acceptance letter in hand, I set off to enroll at Zhejiang University.

Zhejiang University was unlike anything I had experienced

Upon landing in Shanghai, my American classmates and I were piled into a minibus for the two-hour drive south to the garden city of Hangzhou — capital of Zhejiang Province and home to Zhejiang University (affectionately referred to by locals as ZheDa).

After settling into the dorm, which was a single room with a private bathroom, we were welcomed by our professors with a banquet at the college’s canteen — an establishment which was far better than the standardized cafeteria fare that I’d come to know back in New England.

In our dormitory building, for the equivalent of $2 at the time, one could acquire a filling meal any time of the day — from rice porridge and steamed buns in the morning to stir-fried vegetables and sweet and sour pork tenderloin in the evening, all cooked fresh to order.

Zhejiang University was massive and spread across multiple campuses throughout the city. Fortunately for us newcomers, our group at the University’s International College was tucked into a leafy hillside on the historic Yuquan campus, offering a slice of Chinese university life at an approachable scale.

Classes were rigorous and worldly

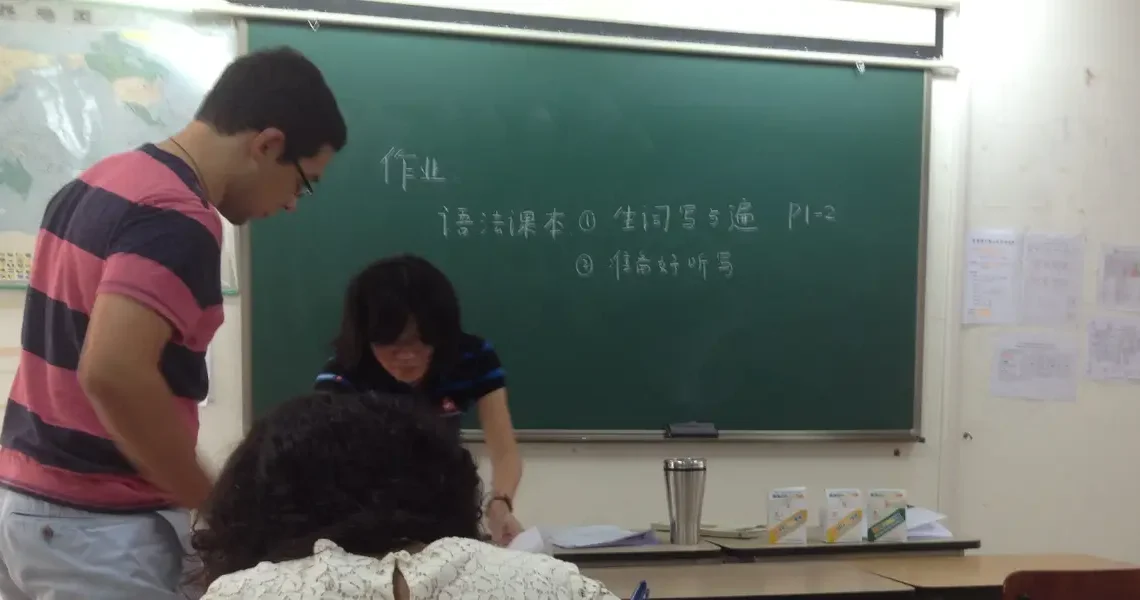

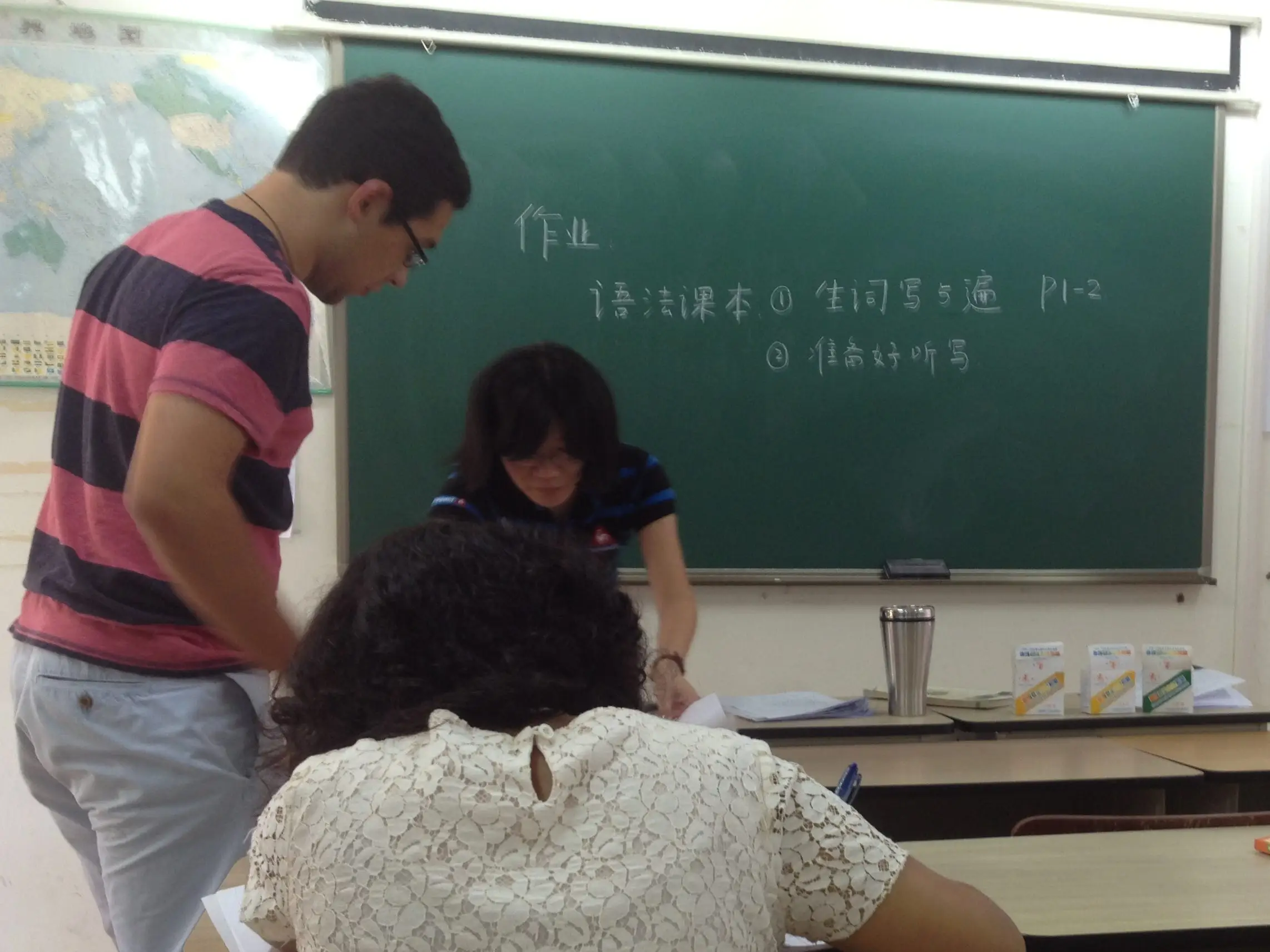

As the sweltering days of summer transitioned into an osmanthus flower-scented autumn, I settled into a new school year. Each morning consisted of four hours of intensive language instruction, followed by at least a few more hours of homework and self-study in the afternoon.

In addition, each week we’d attend one three-hour lecture on Chinese Peasant History with our advisor, who drew heavily from his own experiences as an academic sent to the countryside during Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

I also had a three-hour lecture on the Chinese Legal System with a professor who’d argued many cases within China’s rapidly evolving court system.

American students were very different than the Chinese students

While my application to enroll in Zhejiang University was relatively quick and painless, the road to admission for most of ZheDa’s domestic student population was comparatively long and grueling.

From an early age, they’d studied for hours at school, followed by hours at buxiban (cram schools), preparing to ace China’s notoriously difficult standardized exams, such as the Gaokao. Of the millions who sit for the Gaokao each year, only the highest scorers earn spots in China’s most prestigious schools, such as Peking, Tsinghua, and Zhejiang universities.

Unsurprisingly, the academic work ethic that carried students to Zhejiang University did not fall off after admission. While most of my international classmates would study long hours during the week, we would take Friday nights and weekends off to travel within China. But many local students, however, rarely engaged in such frivolous pursuits and were more likely to be studying in the library on a Friday or Saturday evening.

As exams marked the end of my semester at ZheDa in December 2013, I personally experienced the exacting academic standards that my Chinese classmates were intimately familiar with. While I did pass all of my classes, a minor error in pronunciation or a stroke askew in a written character, mistakes that my Chinese professors back at Tufts may have overlooked, were marked down harshly by my professors at Zhejiang University.

The university is now the best in the world

When scrolling Instagram in January 2025, I saw a familiar sight in a post from The New York Times — a statue of Mao Zedong standing before Laohe Hill and a familiar library, waving to the students on a verdant Yuquan Campus. Reading on, I was proud to learn that my study abroad alma mater had been named the most productive research university in the world by Leiden Rankings, outpacing even my hometown juggernaut, Harvard.

I cannot say that I am shocked by this development. My semester at ZheDa showed me a culture of academic rigor on a scale few American universities can match, drawing from an academic talent pool far larger than in the US.

My time at ZheDa forced me out of my comfort zone and exposed me to an academic world significantly different from that in which I’d been educated, and I believe I am a more open-minded learner for it.

Read the original article on Business Insider

The post I’m an American who studied abroad at Zhejiang University in China. It was unlike anything I experienced back in the US. appeared first on Business Insider.