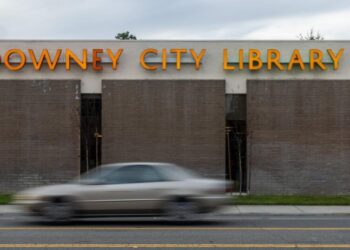

The electric vehicle battery factory that Ford Motor and a South Korean company opened on 1,500 acres of Kentucky farmland last year was the biggest thing, economically speaking, that had ever happened in Hardin County.

Yet in December, only four months after the first batteries rolled off the line, Ford abruptly shut down production and laid off all 1,600 workers, leaving people here in the county, about 45 miles south of Louisville, stunned and angry.

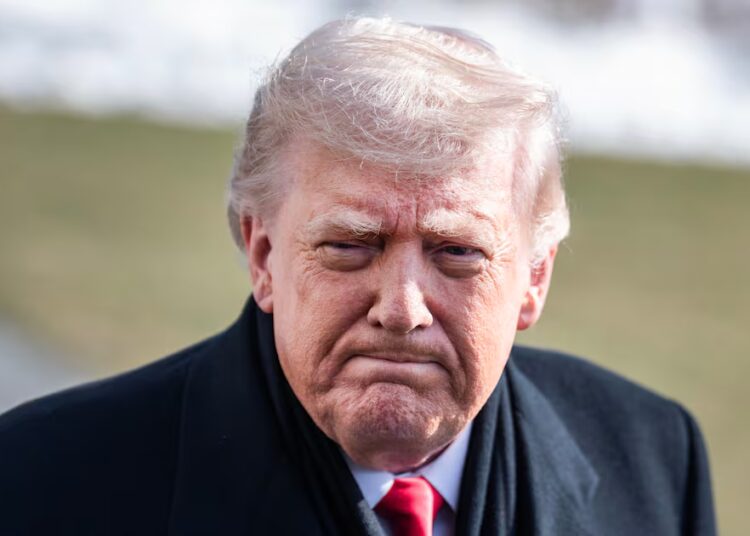

The closing came after President Trump and Republicans in Congress gutted programs designed to promote electric vehicles, causing sales to plunge.

Yet few people in Hardin County, where Mr. Trump won 64 percent of the vote in 2024, place much blame on Republicans.

Many said Ford itself was the biggest culprit, raising their hopes and then dashing them. They said the company’s foray into electric vehicles was a disaster largely of its own making.

The views here in Kentucky highlight how even before Mr. Trump undid many Biden administration policies, established automakers were struggling mightily to master a new technology. Ford and other large manufacturers ignored electric vehicles for years before being caught flat-footed by the rise of Tesla. Then the older companies rushed to catch up by spending billions on new factories.

But it is now becoming clear that those efforts were haphazard and too reliant on government support that proved fleeting. Many of Ford’s early electric vehicles were expensive, and car buyers often considered them inferior to those made by Tesla and other automakers.

Ford’s abrupt decision to reverse course has been wrenching for workers. One of them, Derek Dougherty, said the company had offered him the most stable job he’d ever had. He also received health insurance, a crucial benefit for him, his partner, their 3-year-old daughter and a baby on the way.

When Mr. Dougherty got the news shortly before Christmas that Ford was laying off everybody, his body shook, he said.

“I’ve been homeless for years and all sorts of other stuff, and this was supposed to be the grounding moment,” Mr. Dougherty, 28, said. “We just started renting our apartment over here because of this job. Now that job’s not there.”

He and other workers and officials in Elizabethtown, the main population center in the area, said Ford had misread the market or had been too reliant on subsidies.

“At the end of the day, whatever the government policy would be, the company made the decision,” Mr. Dougherty said.

Sales of electric vehicles have plummeted since the end of September, when federal tax credits worth up to $7,500 ended. The Trump administration has cut subsidies and loans for clean energy projects, while seeking to eliminate regulations that encouraged automakers to sell low-emission vehicles.

“The credit going away in September was the ultimate downfall,” said Andy Games, president of the Elizabethtown-Hardin County Industrial Foundation, an economic development group.

Ford blamed disappointing electric vehicle sales for its change in plans. “The operating reality has changed, and we are redeploying capital into higher-return growth opportunities,” Jim Farley, Ford’s chief executive, said in December when the company announced a $19.5 billion loss on its electric vehicle business.

“We are listening to customers and evaluating the market as it is today, not as everyone predicted it would be five years ago,” Ford said in a statement this week.

Kentucky is not an isolated case. Last year companies canceled $22 billion in planned investments in electric vehicle manufacturing, batteries or critical minerals in the United States, according to Rhodium Group, a research firm. Many projects were in Republican strongholds like Hardin County.

“Those are 1,600 Kentuckians that lost their jobs solely because of Donald Trump pushing that big, ugly bill, eliminating the credits that had people interested and excited to buy E.V.s,” Andy Beshear, the Democratic governor of Kentucky, said in an interview. “I bet many, if not most, of those 1,600 people voted for him, and he basically fired them.”

Demand for electric vehicles was already dropping before the tax credits expired, and other investments in Kentucky have made up for the loss of the Ford plant, a White House spokesman said in a statement, crediting Mr. Trump’s “tax cuts, deregulation, tariffs and energy abundance.”

Ford plans to reopen the factory next year to produce large batteries that utilities, data centers and other companies use to store energy.

Demand for battery storage is strong because of the need to manage fluctuations in energy supply and provide backup power, analysts said. But Ford has no experience making such batteries.

Ford said that the laid-off workers, who had just voted to join the United Automobile Workers union, would be able to apply for jobs when the factory reopened but that they would not be guaranteed positions.

The revamped factory will employ around 2,100 people, not the 5,000 planned for the electric vehicle battery operation, which was originally a joint venture with SK On, a South Korean company. The joint venture ended in December, and Ford became the sole owner.

“We’re still growing in manufacturing and growing in a lot of high-tech areas,” Mr. Beshear said of Kentucky. “But we would be doing even better.”

Still, conversations with people in Elizabethtown, the county seat, which has around 32,000 residents, suggest that Republicans may not pay a steep price for lost clean energy jobs.

Joe Morgan left a job he had held for 24 years to earn $38 an hour as a maintenance technician at the Ford battery plant. Mr. Morgan, a registered Republican, said he had loved the work and believed that electric vehicles would become more popular.

But he said the Ford F-150 Lightning, an electric pickup for which the plant made batteries, and which the company is no longer making, was unaffordable to most people.

“Taking away the tax credits did play a little bit of a role in not selling E.V.s,” Mr. Morgan said. “But to be honest, I just think Ford made a bad decision when they came out with an F-150 that they wanted to make all electric.”

Other residents said Ford was simply the victim of shifting market forces. “A lot of it was factors beyond their control,” said Jeff Key, a retired pharmaceutical executive who grows corn and beans on farmland near the factory. “When demand fell off, they did what a good business should and changed their plan.”

Hardin County is not monolithically Republican. Jeff Gregory, the mayor of Elizabethtown, is a former state police trooper who describes himself as a centrist, gun-owning Democrat. He was re-elected to a second term in an uncontested election in 2022.

Local politics here appears less bitter and polarized than at the national level.

“People around here focus more on the job that people are doing than they do on what the party is on the local level,” Mr. Gregory said.

Keith Taul, who leads the county government, describes himself as a conservative Republican. He was elected in 2022 on a promise to block solar energy projects on farmland. But he speaks highly of Mr. Gregory, and they share disappointment at the shutdown.

“There’s a lot of anger about it,” Mr. Taul said, even among people who “agree with the direction that the president is going.”

State and local officials had tried to find a company to use the site for nearly two decades and were thrilled when Blue Oval SK, the Ford-SK On joint venture, announced its plans for the factory.

It was one of the largest manufacturing investments in Kentucky history. It gave a state long dependent on coal mining a foothold in a high-tech industry.

“It’s a new version of the industrial revolution, it’s a tech revolution,” said Daniel London, executive director of the Lincoln Trail Area Development District, which promotes investment in the area. “To be on the cutting edge of that opportunity is an honor.”

State and local governments spent about $250 million to upgrade local sewer and electricity infrastructure, Mr. London estimated. The Elizabethtown Community and Technical College built a facility near the factory to train workers. Ford and SK On were excused from paying property taxes for 15 years. Elizabethtown even established a sister city relationship with a South Korean city.

The county had an unemployment rate of 5 percent in November, slightly higher than the national average. But the factory paid more and offered better benefits than most other employers, Mr. Taul said.

“We got more people in the community that are able to maybe move up a little bit in their pay scale,” Mr. Taul said. “There’s a ripple effect associated with that. You know, they go out and maybe buy a little nicer car or they go to nicer restaurants.”

Many of the laid-off workers have found new jobs. One of them, Sandie Yarborough, is working on the construction of a data center in Indiana, but she has to commute more than an hour; driving to the Ford factory took 20 minutes.

She has gone to job fairs looking for something closer to home. But, Ms. Yarborough said, “it’s a struggle now trying to find something that’s comparable.”

Jack Ewing covers the auto industry for The Times, with an emphasis on electric vehicles.

The post In Kentucky, People Blame Ford More Than Trump for Lost Factory Jobs appeared first on New York Times.