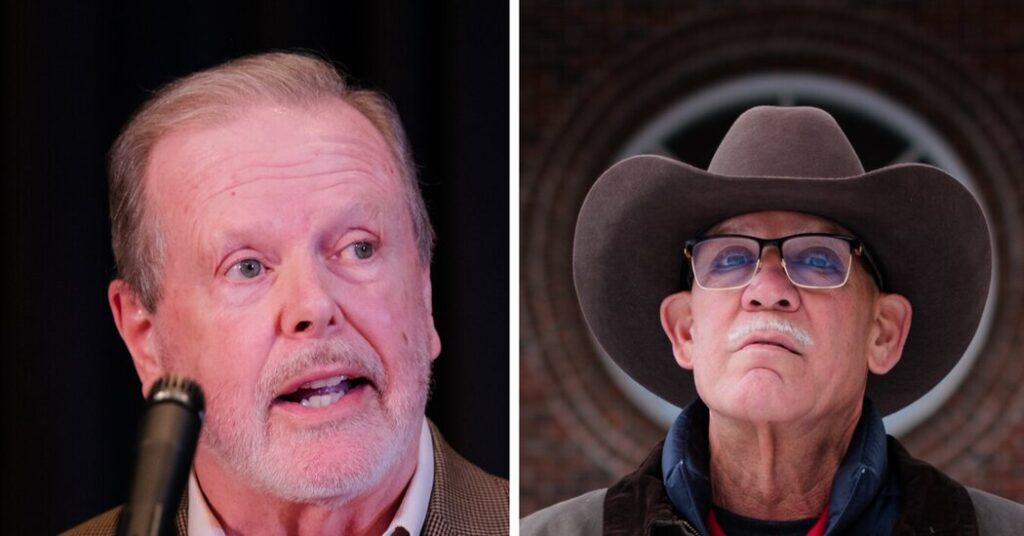

Phil Berger entered the small auditorium at Rockingham Community College and prepared to defend his record to a crowd of MAGA-hat-wearing constituents, with just weeks to go before the primary for his North Carolina Senate seat.

On paper, his odds looked good. He had represented these voters for more than two decades in the State Senate and had led the chamber ever since Republicans took over in 2011. He had built a political machine that in many ways now runs the state. And his clamp on policy decisions, as well as his network of lobbyists and wealthy donors, had turned him into North Carolina’s most powerful politician, making his seat virtually untouchable.

But at the conservative candidates forum at the college in Wentworth, N.C., last week, there was a popular sheriff in town eager to take down Mr. Berger, representing the first time in years that the Senate leader’s reign has been threatened.

“Too many times we elect officials that forget who their bosses are, and whom they serve,” the sheriff, Sam Page of Rockingham County, N.C., told the crowd, flashing his trademark cowboy hat, gray mustache and thick glasses. Several nodded in approval.

To much of North Carolina, the most talked-about race so far this year has not been the high-profile contest for U.S. Senate nor one of the few potentially competitive races in congressional districts across the swing state. Instead, all eyes have zeroed in on a surprisingly tight Republican primary on March 3 for State Senate District 26, a rural stretch of land in the north, that could upend the balance of conservative power in North Carolina.

“North Carolina hasn’t seen a primary race like this in decades, and probably hasn’t ever seen one like this where the stakes could not be higher,” said Andrew Dunn, a G.O.P. strategist and the publisher of Longleaf Politics, a conservative newsletter. “If Senator Berger loses, that creates a gigantic power vacuum in North Carolina politics, and it’s unclear who would fill that.”

President Trump endorsed Mr. Berger last year shortly after the Senate leader spearheaded the approval of a new congressional map that is likely to give Republicans an extra U.S. House seat this year. Mr. Berger has denied accusations that he pushed for redistricting to secure Mr. Trump’s approval.

But even the endorsement has underscored the peculiarities of the race and has mirrored the ways some voters feel about both candidates. Mr. Trump has also been friendly with Sheriff Page, whom he has described as “right out of central casting.” In December, Mr. Trump wrote on Truth Social that he wanted Sheriff Page “to come work for us in Washington, D.C., rather than further considering a run against Phil — Both are such outstanding people!”

For many in rural Rockingham County, Sheriff Page — who has served the county for almost three decades — has been a near-constant affable figure steeped in Trump world. He texts with Tom Homan, the White House border czar, and jokes that the way to fix U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s image is to add “National” to its name so the acronym spells “NICE.”

The sheriff, whose phone wallpaper is a photo of him smiling next to the president, said in an interview that he had been watching a comedy channel on TV when Mr. Trump called to tell him that he wanted to endorse Mr. Berger but that “I want to endorse you, too.”

Sheriff Page told the president that he appreciated the job offer, but he was “committed to the people” of Rockingham and Guilford Counties. There, billboards, TV commercials and fliers advertise Mr. Trump’s adoration for Mr. Berger and portray the sheriff as “shady,” calling him Sombrero Sam and saying he is weak on immigration.

The sheriff said those ads were a farce.

“If you see me toting a shotgun over my shoulder, if you see me riding a horse, or if you see me standing with Donald Trump, it’s not A.I. — it’s real,” he said. “I am who I am.”

Some of Mr. Berger’s allies privately acknowledge that despite all those fliers and hours of ads, the longtime sheriff still has him on the ropes. It has become a campaign for political survival, one that is testing the anti-establishment restlessness coursing through voters of all stripes.

“The way I’ve described it is, I’ve had the opportunity to exercise political muscles that I haven’t had to exercise in a while,” Mr. Berger said in an interview, clenching his fists as if he were flexing. “And it feels good.”

Two very different candidates

In both personality and campaign style, the sheriff and the senator are worlds apart. Sheriff Page, typically wearing some kind of vest and boots, is extroverted. Mr. Berger, rarely seen without a suit, appears more reserved, working his power behind the scenes.

Since at least 2012, Sheriff Page has been hawkish on immigration, even visiting the border. Mr. Berger has mainly prioritized fiscal policy and building up the private sector, which his supporters say has contributed to North Carolina’s being named by CNBC as the best state for business for three of the last four years.

Sheriff Page says his favorite campaign strategy is visiting Walmart and Sam’s Club stores to shake hands. His vehicle is outfitted with campaign stickers. Mr. Berger’s campaign and organizations supporting him have flooded TV airwaves and are likely to spend millions of dollars doing so through the end of his primary campaign, according to two people familiar with his operation who were not authorized to speak publicly.

Mr. Berger declined to specify how much his campaign would spend or what his internal polls showed, but he noted that his team would invest “probably more than we need to” in order to win. In the past, campaigns in tough State Senate primaries have spent anywhere from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Such high spending may cost Republican state senators who are facing tight races in November and need the money in order to maintain a supermajority in the chamber. There are questions whether Mr. Berger, a prolific fund-raiser, will have sufficient money left over for his caucus.

Some polls show that Mr. Berger will almost surely lose in Rockingham County, which accounts for about 40 percent of the votes in the district; the other 60 percent lie in parts of Guilford County.

His poor showing in Rockingham is partly because of what happened in 2023, when the Senate leader tried to rush through legislation that would have brought a casino to the county. The community, deeply conservative and Christian, angrily pushed back on the proposal, prompting Mr. Berger to abandon the measure. But many voters have not forgotten.

Also entangled in the race is the fact that North Carolina remains the only state in the country without an approved budget. As the Republican-controlled chambers remain in a stalemate, mainly over tax disagreements, Mr. Berger’s fate next month could steer the way negotiations go.

On a recent afternoon at the Farmer’s Table, a restaurant in Rockingham County, Sheriff Page waved at customers and talked about the Reidsville High School Rams’ state football championship. Several brought up Mr. Berger.

“He’s like a chameleon,” Sheriff Page said of his opponent’s transformation into a pro-Trump politician, taking a bite from his plate of hush puppies.

“I don’t think we need him anymore,” said Yancy King, a 66-year-old former emergency management worker, arguing that Mr. Berger cared more about his personal interests than about his constituents.

“I know it,” the sheriff said.

The county of about 93,000 is not entirely against Mr. Berger. Some residents, like Wayne Hamilton, 55, said there were tangible benefits from the fact that the most powerful person in the state was a local. He cited the recruitment of a pet food manufacturing facility as an example.

“It’s about what he brings to the table for our county,” Mr. Hamilton said.

Several voters in Guilford County said they were sick of Mr. Berger’s ads, saying the volume felt worse than a presidential election year, which is saying a lot for swing state residents. Others said the Trump endorsement was all the guidance they needed.

That connection has deeply mattered to Mr. Berger, who last year shepherded an immigration bill and a sweeping crime bill through the legislature. Asked what he made of the assertion that Sheriff Page was more like Mr. Trump, Mr. Berger said there was “an old story here in Rockingham County that the most dangerous place to be is between Sam Page and a camera.”

“If that’s what you mean by being more Trumpy, then that’s him,” he added.

At the forum at Rockingham Community College last week, the men were cordial, shaking hands as they took the stage.

In a rapid-fire, punctual tone, Mr. Berger listed off his accomplishments.

“I am the most effective conservative candidate in this race — the most effective conservative leader for legislative Republicans,” Mr. Berger said, adding, “I’ve fought every conservative battle there is and come out on top.”

Then came closing statements. The sheriff stood up and delivered a message about working for “we the people.”

Mr. Berger remained seated as he spoke his closing thoughts. All night, candidates in other primary races had stopped talking as soon as the moderator banged his gavel.

Mr. Berger paused briefly when he was interrupted by a thud at the podium. But then he continued.

“I’m the leader of Republicans in the Senate,” he said. “I ask for your vote.”

Eduardo Medina is a Times reporter covering the South. An Alabama native, he is now based in Durham, N.C.

The post In North Carolina, a Tight Primary Could Upend the Balance of Conservative Power appeared first on New York Times.