Last year, as Immigration and Customs Enforcement hired droves of new agents, the immigration pipeline lost staffers who process asylum claims and preside over court hearings, according to a New York Times analysis of new government work force data.

The redistribution of resources lays bare the priorities of President Trump’s second administration. Mr. Trump made a campaign promise to conduct “the largest deportation operation in the history of our country.” At the same time, the administration has halted visa processing for immigrants from dozens of countries and tightened caps on refugee admissions.

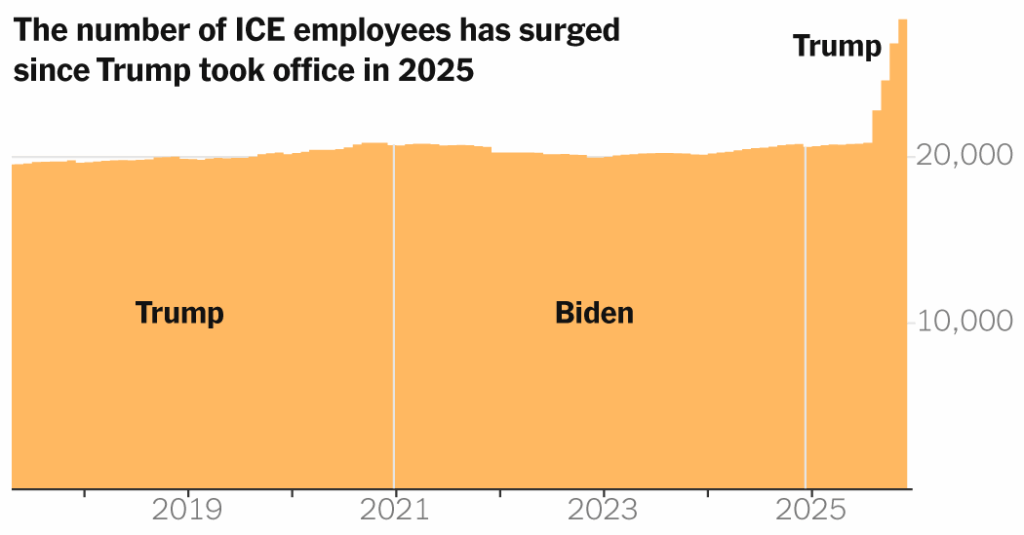

The recent fatal shootings of two American citizens by federal agents in Minneapolis have set off a national outcry and a wave of protests about the unparalleled deployment of immigration agents in American cities. Before agents arrived in Minneapolis en masse, ICE’s work force had grown to more than 28,000, expanding by some 7,500 staff members last year. That’s a bigger expansion than any other government agency.

ICE said in January that it hired about 12,000 officers and agents in less than a year — far more than what the employment data, published by the Office of Personnel Management, show. ICE said the official figures do not yet reflect the full scope of its recent hiring because of reporting lags. Regardless, it’s one of the few places the federal government has been hiring.

Last year, ICE grew by 36 percent while the overall federal work force shrank by about 10 percent, The Times found. The changes were the result of a torrent of cuts by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency and a surge in voluntary resignations.

Agencies that run other parts of the immigration system contracted even further. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which manages visas, green cards, naturalizations and other parts of the legal immigration process, shrank by 11 percent last year. The Executive Office for Immigration Review, which adjudicates immigration cases, lost about 20 percent of its staff.

Customs and Border Protection — the largest immigration enforcement agency — grew by about 1 percent, to more than 67,000 employees.

The ICE hiring surge was made possible by the spending package Republicans passed last year that provided a $75 billion lump sum, which also bankrolled the large enforcement operations in cities like Minneapolis. The agency’s regular annual funding, however, remains a flashpoint. A standoff over Democratic demands for oversight — including bans on agents wearing masks — led to a partial government shutdown in early February.

“We are proud of these new officers, agents and attorneys who are joining ICE’s mission to protect American families and enforce our immigration laws,” Tricia McLaughlin, a spokeswoman for the Department of Homeland Security, said in a statement.

More ICE Agents, and Fewer Auditors

Within ICE, deportation officers and other general enforcement roles grew by 69 percent. That’s nearly twice as fast as the agency grew overall.

In order to ramp up hiring, ICE has sought to hire its own retirees, waived age requirements and reduced the length of training programs. It has offered signing bonuses of up to $50,000 and other perks for new recruits.

That’s led to concerns among law enforcement experts that the lowering of hiring and training standards — and the difficulty of vetting so many people coming on so quickly — could create problems.

Chuck Wexler, the executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum in Washington, pointed to what happened at the Washington Metropolitan Police Department in 1989 when the city was in a rush to hire new officers. Some of the new officers were later arrested on criminal charges.

“It became a national story and a cautionary tale on the importance of basic standards, background checks, psychological screening and training,” he said.

Trump Administration: Live Updates

Updated

- The House is set to vote on canceling Trump’s tariffs on Canada.

- Federal debt is projected to hit record levels, the Congressional Budget Office warns.

- Trump is set to meet Netanyahu in Washington amid tensions with Iran.

Ms. McLaughlin said the fast hiring was necessary to “restore law and order to our communities.” She previously described agents as “highly trained in de-escalation tactics.”

Workers in their 20s made up a disproportionate share of the new enforcement hires, the data show. The newly released data do not detail where agents were stationed, or provide any information about their race or gender.

Some parts of the agency contracted. The number of auditors and accountants shrank, as did information technology and human resources management staff members.

Jason Houser, a chief of staff of ICE under the Biden administration, said that failing to hire enough support positions has been a problem at other times in the agency’s history when employment has surged. Often those jobs end up getting backfilled through contractors, who might be less experienced. Mr. Houser compared it to building a house: “If you put all the money into the home in the kitchen and not the foundation, you’re going to have leaks.”

A Legal Process in Retreat

Last year, U.S.C.I.S., the legal-immigration agency within Department of Homeland Security, lost about a quarter of its staff language specialists, whose tasks include providing translations during immigrant interviews. It saw a similar drop in information specialists, who handle freedom of information requests and ensure that confidential information is protected.

The agency lost nearly 200 employees in the “hearings and appeals” job category in the government data — a 14 percent drop. Those employees are officers responsible for evaluating asylum claims, a Times review of postings on USAJobs.gov, the federal jobs website, shows.

“Our work force changes ensure government resources are used more wisely and focused on the highest priority issues, including the war on fraud and protecting American citizens,” said Matthew J. Tragesser, a spokesman for U.S.C.I.S.

Last year, the agency removed a page from its website that during the Biden administration highlighted its mission, saying that it “upholds America’s promise as a nation of welcome and possibility with fairness, integrity and respect for all we serve.”

The agency has also rebranded immigration officer roles as “homeland defenders.” It has replaced standard language on job postings with calls to “protect your homeland and defend your culture,” seeking workers to fight against “illegal foreign infiltration.”

Mr. Tragesser said the new officers would conduct interviews, review cases and be better equipped to identify “fraud, criminal aliens and national security risks.”

“I wasn’t ready to retire,” said Michael Knowles, a former asylum officer and president of A.F.G.E. Local 1924 who left the government in October after more than three decades. Mr. Knowles became concerned that the administration’s actions placed refugees in harm’s way.

“I could not, in good conscience, be part of it anymore,” he said.

A Staffing Exodus in Immigration Courts

The wave of departures at Executive Office for Immigration Review, which is under the Justice Department, was driven in part by a spate of firings and resignations of judges who decide matters like asylum claims and deportation cases.

Jeremiah Johnson, the executive vice president of the National Association of Immigration Judges, was fired last year from his role as an immigration judge in San Francisco alongside more than a dozen of his colleagues. Mr. Johnson and other fired judges are challenging their terminations in court.

Mr. Johnson said that without enough judges, “you have ICE just removing people, and you just trust that they’re going to vet it correctly.”

The agency declined to comment on The Times’s analysis. Kathryn Mattingly, an agency spokeswoman, said in a statement that it “remains committed to hiring immigration judges” while also “complying with the administration’s goal of reducing the size of the federal work force.”

The cuts are a reversal from the first Trump administration, when the courts and the legal immigration system grew far faster than ICE did.

Despite that growth, the courts have faced case backlogs, said Doris Meissner, a director at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute and a top immigration official in the Clinton and Reagan administrations. She said that though immigration enforcement is necessary, further diminishing the courts strains checks on the system.

Without more balanced hiring, “the system is not going to do what it’s supposed to do, which is respect the rule of law,” she said.

Alexandra Berzon, Alicia Parlapiano and Alex Klavens contributed reporting.

Andrea Fuller is a data journalist at The Times, using data analysis to make sense of complex topics.

The post ICE Hired Thousands While the Rest of the Immigration System Shrank appeared first on New York Times.