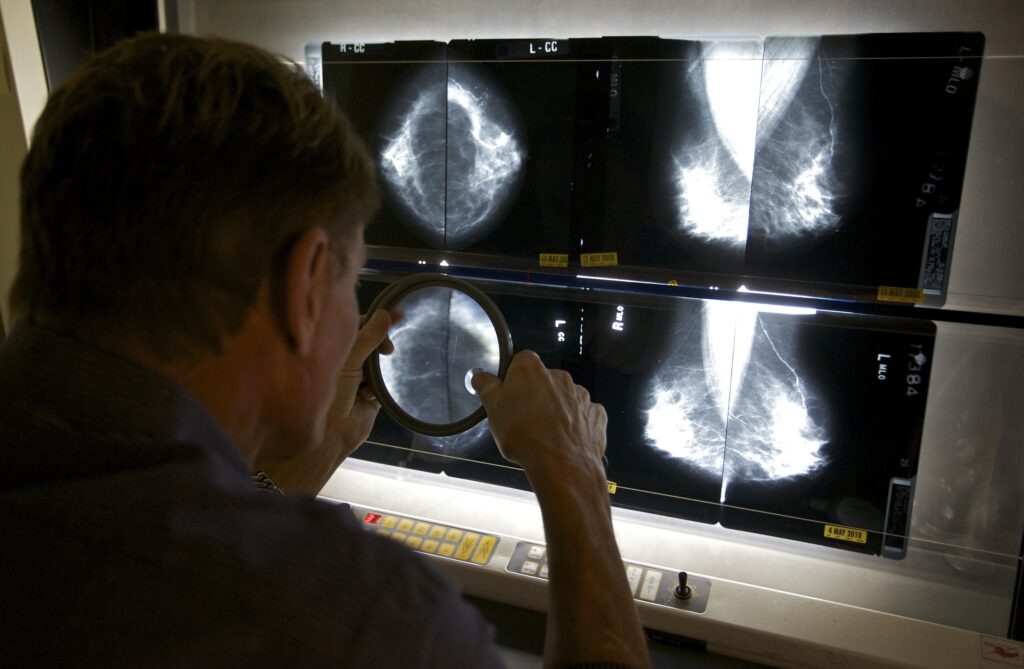

For decades, breast cancer screening has been synonymous with the mammogram. Women’s preventive care has centered on the annual test, and for good reason: 1 in 8 women in the United States are diagnosed with breast cancer during their lifetimes, and early detection is key to making sure it doesn’t spread.

Recent research challenges this long-standing approach, however. A major study published in JAMA suggests the most effective screening strategy is based not on the yearly mammogram, but genetic testing combined with an assessment of individual risk factors.

Laura J. Esserman, the study’s lead author and director of the Breast Care Center at the University of California at San Francisco, told me that a one-size-fits-all mammogram recommendation comes with downsides. Women at higher risk may need more frequent surveillance, while those at lower risk are subjected to unnecessary yearly anxiety, inconvenience and costs. False positives are also a major concern: Studies show that 75 percent of biopsies prompted by abnormal mammogram findings turn out to be benign.

Instead, she asked, “What if we could put together an algorithm that would really identify the highest-risk people and people at risk for the most aggressive diseases?” Those individuals could receive more intensive screening, while others safely undergo mammograms less often.

Esserman and her colleagues tested this approach in a large national trial involving women between the age of 40 and 74. Roughly 14,000 participants were randomly assigned to follow existing guidelines and continue annual mammograms. Another 14,000 tried the risk-based screening strategy.

Women in the latter group underwent genetic testing along with an evaluation of their family history, lifestyle risks and medical conditions. Based on these results, participants were assigned to one of four screening schedules. Those at highest risk — about 2 percent of participants — received recommendations to get screened every six months, switching between MRIs and mammograms. Women at elevated risk (8 percent) followed current recommendations for annual mammograms starting at age 40. Those at average risk (63 percent) were suggested to screen every two years, while women at lower risk were told they could delay screening until age 50.

This approach was as effective as annual mammograms at detecting breast cancer overall,including among women at highest risk. Although cancers were more common in that group, there were no cases of advanced-stage disease. If implemented nationwide, Esserman estimates this strategy could reduce advanced cancers by about a third and save up to 5,000 lives each year.

Another striking finding: 30 percent of women who tested positive for genetic variants associated with increased breast cancer risk reported no family history of the disease. Under current medical practice, these women would not have been offered genetic testing and wouldn’t have known they had elevated risk.

Esserman argues health experts need to rethink breast cancer screening altogether. Rather than recommending mammograms for every woman beginning at age 40, she believes screening should start with genetic testing at age 30. Clinicians could then use those results, alongside other risk factors, to determine when and how often to do mammography.

This will be a novel concept for many people, but it has both scientific and practical merit. Genetic tests cost less than a mammogram and generally only need to be done once. If risk-based screening allows some women to safely avoid mammograms, the potential savings could be substantial. In the U.S., exams cost a total of about $11 billion each year.

More importantly, personalized screening does something mammography cannot: It helps identify high-risk people early enough to act. After all, imaging tests can detect cancer, but they do not prevent it. Many breast cancer risk factors are changeable, including smoking, excess weight, lack of physical activity and heavy alcohol use. Indeed, this trial found that informing higher-risk women about such factors led to substantial improvements to health-related behaviors.

High-risk women should also consider preventive drug therapy. Medications such as tamoxifen, raloxifene, anastrozole and exemestane can lower the long-term risk of developing breast cancer in this group by 30 to 65 percent. Yet despite strong evidence of benefit, many women are never offered these medications. In this study, use of preventive chemotherapy doubled among high-risk participants, driven in part by greater awareness of these options.

These findings could mark a turning point in cancer prevention. The results are so convincing that some clinicians and hospital systems will start administering risk-based assessments now. I hope major medical organizations — including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which determines insurance coverage — will follow by updating their guidelines. At minimum, genetic testing should be offered to all women, regardless of family history.

Esserman told me the study was difficult to carry out in part because of resistance within the radiology community to changing entrenched practice. Patient advocates, too, may be reluctant to move beyond a mammogram-only mindset. But everyone involved with breast cancer care should focus on the more than 42,000 women who die annually from this disease and prioritize interventions that have the greatest impact.

What are your thoughts about the individualized risk-based approach to breast cancer screening? I’d love to hear from you and to feature your comments in The Checkup newsletter.

The post We may be doing breast cancer screening all wrong appeared first on Washington Post.