The people want affordability, and Donald Trump knows it. After initially calling the concept a “hoax,” the president has begun unveiling his own agenda to bring down prices and increase Americans’ purchasing power. Somewhat astoundingly, each of his proposals, if enacted, would be more likely to make the affordability problem worse, not better.

Trump’s signature idea is simply to give people money. In November, he promised to send out a “tariff dividend” of $2,000 to all but the highest-earning Americans sometime in 2026. This plan, which he has continued to promote, would almost certainly require an act of Congress, meaning that it’s unlikely to happen. That’s a good thing. Handing out free money would make voters happy in the short term but would ultimately backfire. This is because a massive one-time influx of cash is likely to create far more demand than the economy can possibly meet. Consumer spending is already strong, unemployment is already low, and inflation is still too high. “I’m usually all for giving people money,” Natasha Sarin, the president of the Yale Budget Lab, told me. “But a move this dramatic in our current macroeconomic environment is a recipe for inflation.”

America has very recent experience with this dynamic. In the spring of 2021, the Biden administration passed a spending package that included sending out more than 150 million stimulus checks of up to $1,400, fulfilling a campaign promise. When the country reopened, that money flowed into an economy whose supply chains were still disrupted. With too much money chasing too few goods, inflation took off. The spending package wasn’t the main cause of post-pandemic inflation—which, after all, occurred around the world—but economists broadly agree that it pushed inflation up by at least a few percentage points. You might think that Trump, of all people, would have internalized this lesson, given that he spent much of his 2024 campaign blaming inflation on Biden’s reckless spending.

[Rogé Karma: The debate that will determine how Democrats govern next time]

If sending out checks is a bad idea, what about tackling the housing crisis? Last month, Trump issued an executive order directing various government agencies to draft regulatory guidelines and Congress to write legislation that would prevent corporate investors from purchasing single-family homes. “Hardworking young families cannot effectively compete for starter homes with Wall Street firms and their vast resources,” the order declares. “My Administration will take decisive action to stop Wall Street from treating America’s neighborhoods like a trading floor and empower American families to own their homes.”

The notion that Wall Street is to blame for high housing costs is widespread among left-wing populists. It is also wrong. Large institutional investors, typically defined as those owning more than 1,000 homes, control just 0.5 percent of the single-family housing stock in the country. (The executive order itself doesn’t actually define what qualifies as an institutional investor.) That share is higher in specific neighborhoods in certain cities, including Cleveland, St. Louis, and Baltimore—which, notably, are among the places where housing costs haven’t gotten out of control. Meanwhile, the cities that have experienced the largest price increases over the past 15 years, such as San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles, have some of the lowest percentages of institutional investment.

The weight of the evidence suggests that institutional investors actually make single-family homes more affordable. It is true that when a Wall Street firm buys a home, it decreases the total number of homes for sale, which pushes home-purchase prices up. But it also increases the number of homes available for rent, which pushes rental prices down. In this sense, institutional investment is functionally a downward redistribution of wealth from homebuyers to home renters. One recent study found that single-family-home rents in Atlanta would have been 2.4 percent higher without the presence of institutional investors, costing renter households nearly $3,000 a year on average. Another study, which analyzed a wide range of otherwise similar metro areas that had varying levels of institutional investment, found that these two forces are not symmetric. Institutional buyers push rents down slightly more than they push home prices up.

A ban on institutional investors, in other words, would have basically no impact on overall home prices at the national level while likely raising rents in the places where investment is most concentrated. Perhaps that is part of the appeal for Trump, who seems to want credit for tackling high housing costs without doing anything to actually lower them. “I don’t want to drive housing prices down,” the president admitted at a recent Cabinet meeting. “I want to drive housing prices up for people that own their homes.”

In yet another rebrand of a left-wing populist idea, Trump has also called on Congress to pass a one-year cap of 10 percent on credit-card interest rates. Consumers spend about $150 billion every year paying off interest on their credit cards. Rates average about 20 percent and can reach as high as 35 or 40 percent. In theory, capping the rate at 10 percent would save consumers tens of billions of dollars while redistributing wealth from big banks and their shareholders to the low-income consumers who typically carry credit-card debt.

[James Surowiecki: Trump doesn’t understand inflation]

The success of the proposal, however, hinges on how exactly the credit-card industry responds to the price cap. A major reason credit-card companies charge such high interest rates in the first place is to cover the losses incurred when cardholders don’t pay their balances. Some proponents argue that if those interest rates were capped, banks could simply absorb those losses by accepting lower profits or slashing their marketing budgets. But several studies have found that banks tend to respond to even small regulatory changes to the interest rates they can charge by issuing less credit to their highest-risk borrowers. There might be a point at which that’s worth the trade-off—but a cap as drastic as 10 percent is probably far past that sweet spot. “The literature is really clear on this,” Sarin, who specializes in banking regulation and recently co-authored a paper on the subject, said. “When you reduce how much banks can charge, you increase their risk—and that changes who they are willing to lend to in the first place.”

The individuals who would be most likely to lose credit-card access in this scenario—borrowers with low credit scores—are the same people who tend to rely on short-term debt to make essential purchases, such as groceries, gas, and medical bills. Without credit cards, they would likely be forced to rely on more expensive, less regulated, options such as payday loans, which can come with rates as high as 400 to 500 percent. Fear of that outcome may be why Trump has proposed limiting the cap to a single year. But a temporary version runs into another problem: Once the cap expires, credit-card companies will likely respond by jacking up their interest rates even higher than before to make up for their losses. “It’s not like this would put Chase or Bank of America out of business,” Ted Rossman, an analyst at Bankrate, a company that helps consumers compare credit cards, told me. “But it would be a huge hit to the industry. And it would be a huge hit to the consumers who depend on credit cards the most.”

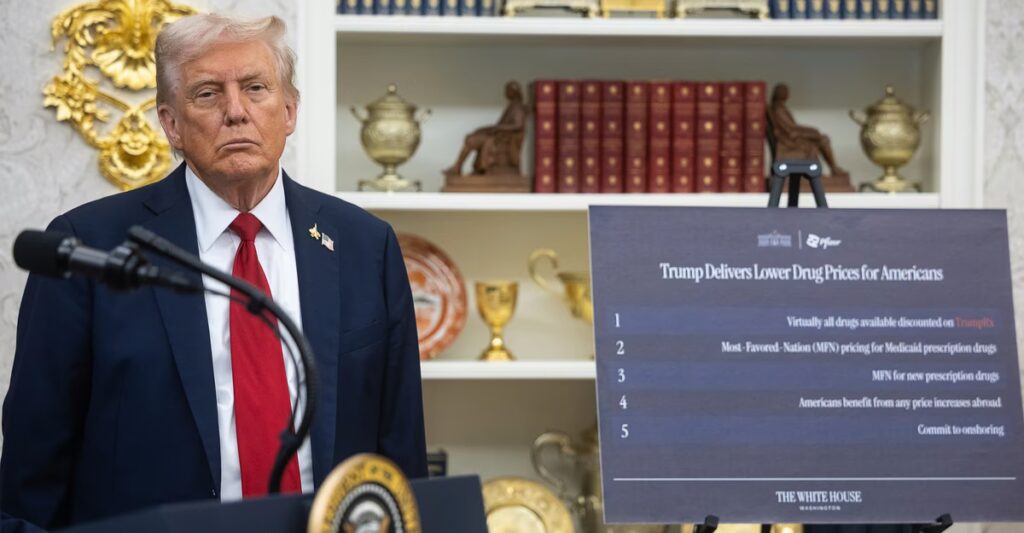

Even in the one area in which Trump has notably succeeded at lowering some prices, he has still managed to make life less affordable overall. Last year, his administration announced a series of deals with pharmaceutical companies to lower prices of a few dozen drugs, including some eye-popping decreases of anywhere from 55 to 98 percent. But as with drug commercials, one must pay attention to the fine print. In order to qualify for the discounts, individuals must buy the drugs directly from the manufacturer through a government-run platform called TrumpRx and, crucially, cannot use insurance to do so, making the program basically irrelevant for 85 percent of Americans. (The order also claims that the new prices will be made available to “every State Medicaid program,” but there is no evidence that has happened or will.)

[Nicholas Florko: The real winner of TrumpRx]

These one-off deals haven’t altered the behavior of the pharmaceutical industry. Drug companies raised the prices of nearly 1,000 drugs at the beginning of this year, and the median overall increase, about 4 percent, was the exact same amount they raised prices by the prior year. The Trump administration has also handed them some major concessions. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act that Trump signed into law last year includes a provision that exempts or delays several drugs, including some of the most popular and expensive cancer medications, from having to participate in price negotiations through Medicare. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that taxpayers will pay $8.8 billion more over 10 years for these drugs relative to what they would have paid if negotiations had taken place on schedule.

Most of the real solutions to the affordability problem, such as building more housing and reforming the health-care system, would require years of sustained effort, large investments, and hard political trade-offs. (The obvious exception would be the repeal of Trump’s global tariffs, which the president could do tomorrow.) But voters want affordability right now and have proved that they are willing to throw out politicians who don’t deliver it. Trump’s response to this has been to float policies that promise a quick hit of relief. He might not be operating in good faith, but whatever president succeeds him will have to wrangle with the same dilemma.

The post Trump’s Affordability Ideas Would Probably All Backfire appeared first on The Atlantic.